New ideas for the old UKCS

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 18

By William Powell

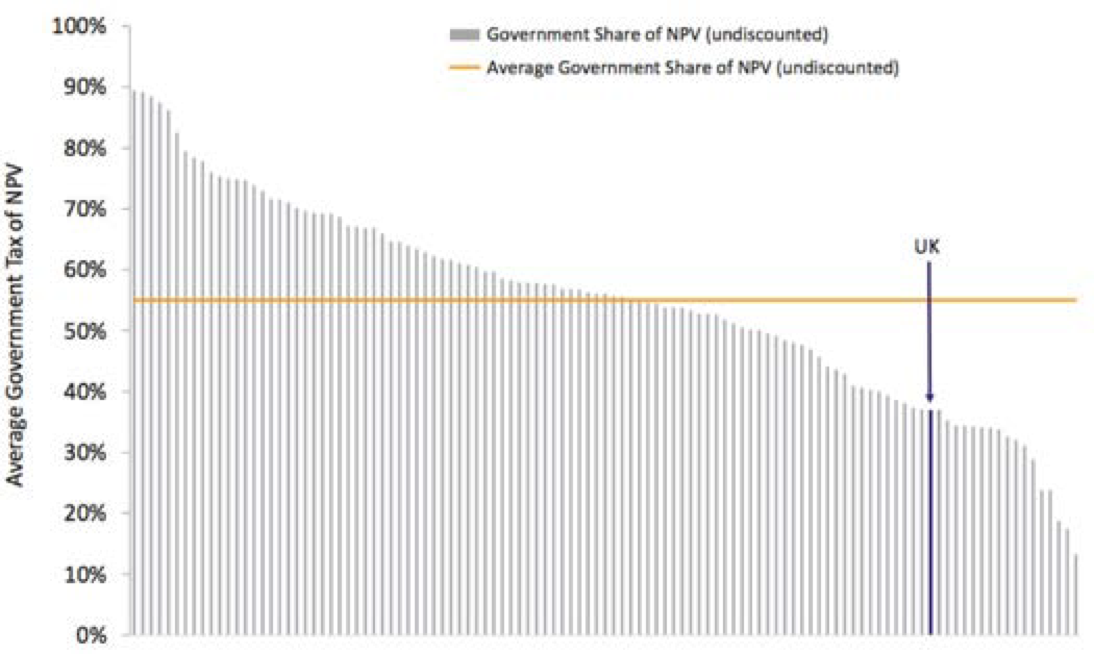

Maximising the economic recovery of the UK Continental Shelf is a policy that could ultimately become a job for government; but for now the focus is on making things – access to data, technology and the fiscal regime – as enticingly simple and attractive as possible.

The UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) has seen a brisk wave of mergers and acquisitions over the year, with almost $6bn notched up since January, in seven reported deals. The low oil prices have attracted new capital that can see opportunities where the sellers cannot. This compares with a total $8bn in the period 2014-2016.

Most of the value of the asset sales this year was the Shell sale to Chrysaor, where the Anglo-Dutch major took the opportunity to offload some of its more expensive to run assets such as Armada, Erskine and Everest, spiced up with the Schiehallion stake. Chrysaor financed it with a reserves based loan for $1.5bn over six years, which it described as one of the largest in the UK North Sea.

Those assets were valued at $3bn. Other UK assets were included in Engie's $3.9bn upstream sale to Neptune; in Dong's $1.05bn sale to Ineos; Delek's takeover of Ithaca and Oranje-Nassau Energie's purchase of Sterling Resources UK.

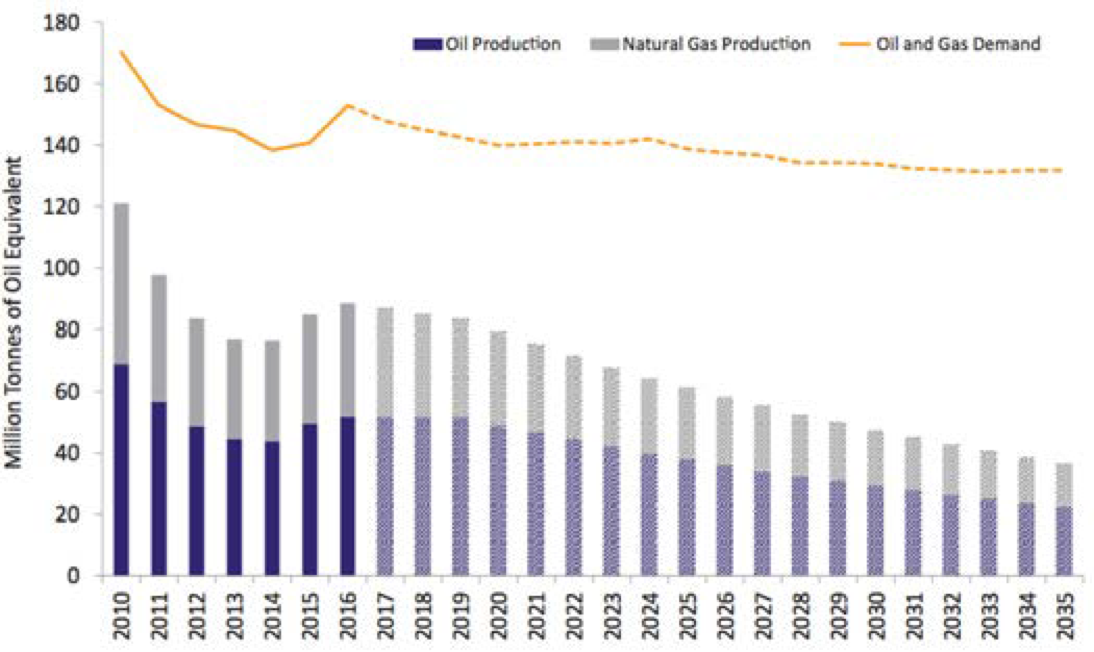

The lag between investment decisions and their results means that since 2014, when oil prices fell, oil and gas output has gone up 16%; and lifting costs over the same period have almost halved. This year too output will probably be up on last year as production so far is already 1% up on the same eight months of 2016 – thanks partly to the recent start of Total-operated Glenlivet and Edradour fields.

But the trend is downwards: last year there were nine start-ups; this year, there will be eight; and once the big fields that were committed before the oil price fell – such as Clair Ridge, Mariner, Culzean and Catcher – have come onstream there will be very little to replace them. By the end of 2018, a third of UK output will come from fields that were not even operational in 2015.

Cuts in capital expenditure since 2014 mean that very little new exploration is planned. Exploration and appraisal wells remain a serious concern with UKCS drilling at record lows, and only three new field approvals sanctioned since the start of 2016. If activity does not pick up this could have further negative implications for jobs that could threaten core capabilities, the report says.

However, the fact that assets are changing hands as new kinds of companies see value does suggest that the UKCS may start to benefit from a badly needed investment boost, the report says. OGUK believes that efficiency gains, fiscal competitiveness and world-class supply chain differentiate it from other basins. The challenge now is to ensure this renewed interest in the basin translates into tangible activity that could help unlock around £40bn ($52bn) worth of potential development opportunities known to be in company business plans. Of that, about a half is brownfield and so presents fewer unknowns.

While investors still want more certainty over Brexit and clarity over the role of oil and gas through a more comprehensive energy policy, the transformation underway is restoring the UK’s position as an attractive basin for investment – and one still supporting over 300,000 UK jobs, it says. Brexit though could be a benefit: trade now costs the UK £600mn/yr, which could fall to £500mn given a favourable trading environment with the rest of the world; however if World Trade Organization rules apply then the cost of trade will almost double to an estimated £1.1bn.

OGUK says this is because tariffs would be applied to UKCS imports of services, fuel, and equipment and other goods. Those estimates, which have input from EY, exclude the additional, hard to quantify non-tariff barriers that could arise after Brexit. OGUK says it is hoping is for "frictionless access to labour and markets."

OGUK CEO Deirdre Michie told the Offshore Europe conference in Aberdeen early September: “There are still serious issues facing our industry which has suffered heavy job losses since the oil price slump. But we are hopeful that the tide is turning and expect employment levels to stabilise if activity picks up. Our sector is successfully re-positioning through efficiency and cost improvements.... We are increasingly being seen as a much more attractive basin in which to invest with further M&A activity expected over the remainder of this year and into the next."

She also said that government can continue to play its part, by developing a clear energy policy that reinforces the role for oil and gas in the Industrial Strategy, supporting a Sector Deal and confirming in the Autumn Budget, due in November, that decommissioning tax relief will be modified to support further investment activity. “It’s vital that industry and government work together to secure our future. There are billions of barrels of oil and gas still to go after in our own back yard. Government and industry must make the most of the opportunity offered by our sector.”

New approaches

The upstream regulator Oil & Gas Authority (OGA) and the industry have been working on some of the low-hanging fruit such as efficiency gains. One example is the ‘tie-back of the future,’ which depends on operators buying standardised equipment which can be used with little modification, and then be refurbished for use at another site afterwards, rather than the operator commissioning bespoke parts for one-off use. This reduces abandonment costs as well.

This is especially necessary, says the freshly-minted, state-backed Aberdeen-based £180mn Oil & Gas Technology Centre (OGTC), for the small pools of oil and gas, whose life span will only be three or four years. The more equipment can be re-used, the more the economics will improve.

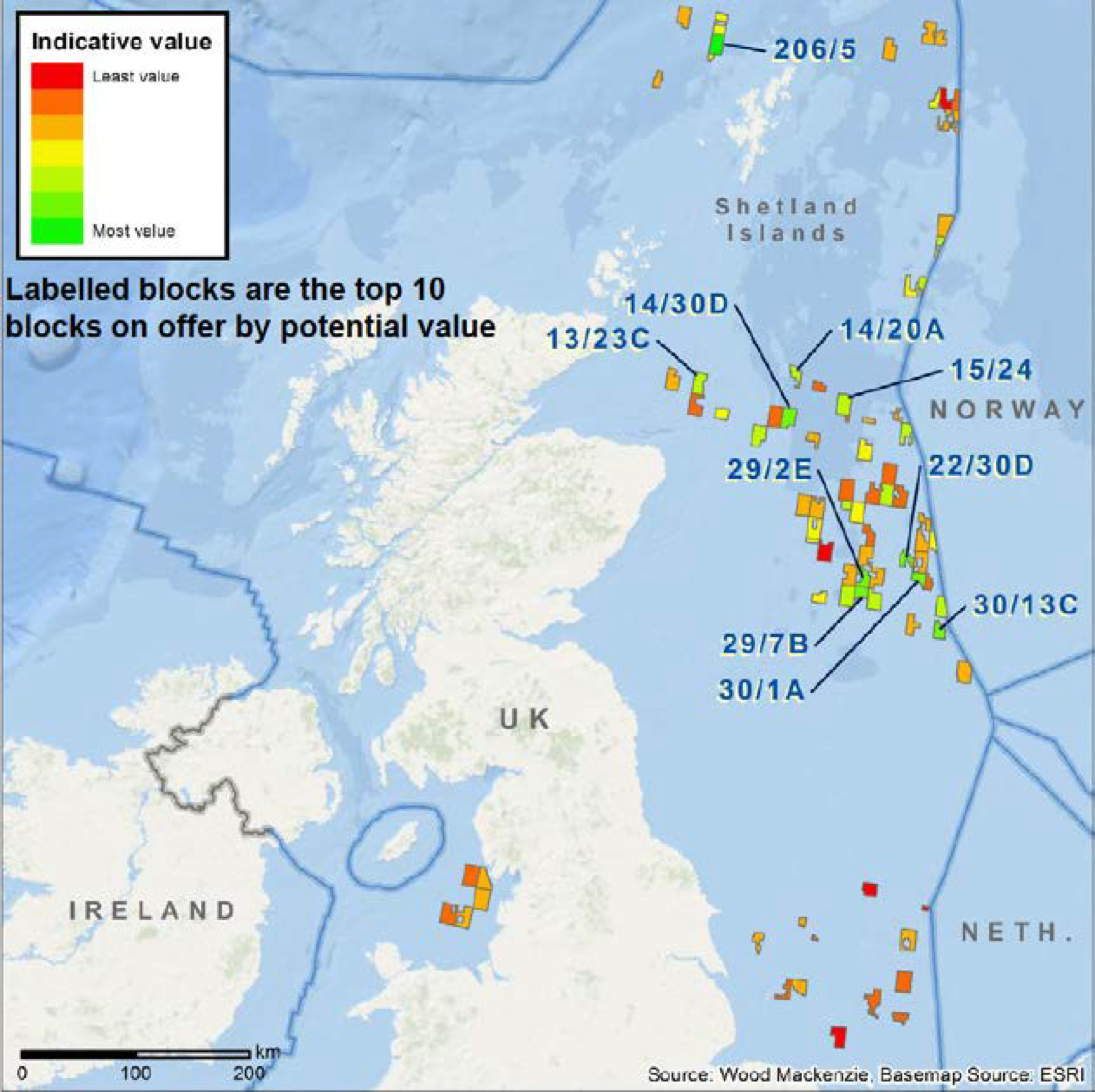

Analysts Wood MacKenzie said in a report that there could be some 3bn barrels of oil equivalent in 275 small pools that are too far from infrastructure to merit development. The average size of these is 18mn boe and are not going to be a priority for development: only half are economic at $50/barrel, but two thirds could be if a different approach were taken to subsea technology.

The OGTC’s ‘tieback of the future' is part of a new approach to the problem, possibly halving the cost of subsea facility and abandonment costs, and halving too the time it takes from final investment decision to first oil, report author Kevin Swann told NGW.

At current exploration rates, it would take 14 years and 500 wells to discover this same volume. As an ultra-mature region, this level of discovered resource can no longer be ignored. As well as providing much-needed new investment for the sector, small pools could provide vital volumes to existing infrastructure hubs; or even allow new ones to come into being. Small fields that form a sufficiently tight cluster could be tied back into a single floating production, storage and offtake vessel, he said.

Woodmac estimates that there are 1.1bn boe on offer in the ongoing 30th Round from 96 discoveries; of those, a third, accounting for 640mn boe are potentially economic today; and this could be extended to 48 and another 760mn boe using such a tie-back approach. The OGTC is working on other ways to overcome inertia, but this will require help, and OGA is exerting pressure on companies that are neither investing or making way for others who want to do so.

Derisking decommissioning

Industry and the finance ministry have been working this summer on a way to allow the transfer of tax history from seller to buyer, and so facilitate asset sales. The upstream is hoping that the autumn budget will allow taxation paid to be calculated on a field as well as a corporate basis. This would be a very complex set of sums which will at least enable the buyer of a stake in a field – perhaps a company with no tax records in the UK – to claim back the tax, when decommissioning comes, that has been paid by the seller over the years to date. Otherwise technically the buyer will have to pay the full cost of decommissioning itself; or at least much time will be spent on complex 'workaround' deals.

One company that has not got to worry about that is Siccar Point, which now has stakes in three of the four biggest fields, all yet to produce and so with a blank tax record: Schiehallion, Mariner and Rosebank. Established in 2014 before the oil price fell, it is now the eighth largest resource holder, following last year’s deals that included OMV’s entire UK upstream business.

CEO Jonathan Roger said the private equity backers – Bluewater and Blackstone – had to be convinced of the target’s value, and that exiting would be profitable within a few years if necessary. The oil price fell after the process of negotiations had begun, and it took the sellers some time to come to terms with the new reality, he said, as they did not like write-downs and it was not until late 2015-early 2016 that they accepted the oil price would be lower for longer. Nevertheless, he said, Siccar was in the UK to invest in the assets, and not wait for prices to rise again, and he said the company would be there for decades to come. He cited research showing that it had the potential to be the biggest company by production in the UK, after BP and Shell.

Most of the company’s efforts are directed at oil but there is potential for a gas hub in the west of Shetland area north of Laggan Tormore: a 1.5 trillion ft³ reservoir, he said.

Commenting on the new optimism, Deloitte said the UKCS has cut operational costs and a significant uptick in merger & acquisition activity across the sector gave rise to a new confidence. "Assets are finding their way into the right hands and a new cohort of private equity-backed businesses is breathing new life into the basin," it said.

The CEOs of both Shell and BP told the Offshore Northern Seas conference in Aberdeen September 5 they believe there is much more oil and gas to be produced from the UK North Sea but called for new fiscal incentives and ongoing efficiency improvements.

Shell CEO Ben van Beurden said that the North Sea still was key to the company’s future, despite the sale to Chrysaor and the decommissioning of the Brent system, but more needs to be done. He referred to the need to put the assets in the right hands, but some of the older assets are never going to be wanted, and the challenge is to dispose of those as well. Analysts at the time said that it was shrewd of Shell to make the deal more exciting, using a stake in Schiehallion to make the aging BG gasfield assets such as Erskine and Lomond more palatable. Both of those were on prolonged maintenance this summer, forcing cuts in guidance for some producers.

BP CEO Bob Dudley remarked in his speech: "In this tough environment, we see the North Sea turning things around. Costs are coming down and oil production is back up. There is plenty of life left in the basin, but it has never been a basin of easy barrels – even less so today after 5bn barrels of production. We have to be highly competitive, cost-efficient and disciplined, and then a step beyond that."

BP is also selling assets: formerly the biggest gas producer in the North Sea, it is retreating, partly to raise money and partly to focus on growth areas, such as its Rosneft partnership and major projects. Most of these are gas and outside the UK: Oman, Egypt, Trinidad and Indonesia, for example.