Moldova’s gas crisis explained [Gas in Transition]

Moldova was plunged into an acute energy crisis last month, after Russia, the supplier of all of its gas, jacked up prices and cut delivery volumes. As a result, Russia has faced condemnation from the EU and other observers for using its gas as a geopolitical weapon, but the reality is more complex.

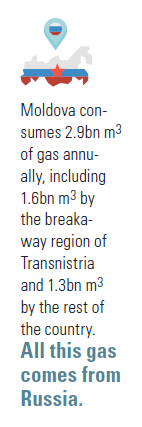

Moldova is a small gas market with only 2.9bn m3 of annual consumption. Of this amount, around 1.3bn m3 is consumed in Moldova proper, while the remainder is consumed in the breakaway region of Transnistria. With no gas production of its own, Moldova is 100% reliant on imports from Russia, and Gazprom also owns half of Moldova’s national gas supplier Moldovagaz, which also comprises its gas transmission operator, Moldovatransgaz.

Until the end of September, Moldova received Russian gas under a long-term contract that had been extended on an annual basis. A one-month extension was agreed only a few hours before the old one’s expiry, and according to Moldovagaz, this meant Gazprom had no means of reserving the necessary transit capacity via Ukraine, and so cut supplies by a third.

At the same time, Moldova had to pay a much higher price for gas last month of $790/’000 m3, versus an average of only $148/’000 m3 in 2020. Like many of Russia’s European gas customers, Moldova had wanted the price it paid to better reflect those at European gas hubs, and in January 2021, it amended its old, oil-indexed contract to use a German NCG month-ahead hub indexation for the warmer second and third quarters of the year, while keeping oil price indexation for the colder first and fourth quarters.

As Katja Yafimava, senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, noted in a recent paper published by the Carnegie Moscow Center, “the prevailing expectation was that low prices would continue into 2021, thus giving Moldova every incentive to seek some degree of hub price indexation.”

This did not prove to be the case, however, and European hub prices increased over this year, with a sharp rise occurring from August onwards. Under the short-term extension agreed with Gazprom for supplies in October, the price was set according to the same hub indexation as in September, resulting in a spike in Moldova’s bill.

A state of emergency

Facing an unprecedented energy crisis, Moldova’s government declared a state of emergency on October 22. It reached out to suppliers in Poland and Ukraine for extra gas, but had to pay even higher prices than it did to Gazprom. It bought supplies from Poland’s PGNiG, for example, at around $1,110/’000 m3, auction data shows.

“These purchases made it abundantly clear to Moldova that the only affordable way out of the imminent gas crisis was to secure a contract with Gazprom at a price lower than the hub-based price,” Yafimava notes.

Moldova therefore entered into a new five-year supply contract with Gazprom on October 29. While its terms have not been officially disclosed, the Moldovan press has reported that it takes into account the prices of oil and gas in the preceding nine months, with a 70-30 ratio between oil and gas price indexation.

The crisis also comes less than a year after Moldova elected a new, pro-West president, Maia Sandu, replacing the Russia-leaning Igor Dodon. Moscow has consequently been accused in the media of manipulating the situation to wield political influence over the new government. The Financial Times, for instance, reported in late October that Russia was imposing political conditions for signing the contract, including Moldova’s withdrawal from the EU’s Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area.

Reasons and motives

So did Russia exploit the situation on the gas market for its geopolitical gain, seeking to keep Moldova closer within its orbit? Or is Moldova to blame for leaving itself overly exposed to volatile market gas prices, which Gazprom, like any other supplier, was under no obligation to undercut?

“Observers in the media either believe one or the other – there is not much of a balanced approach to the issue,” Denis Cenusa, researcher at the Institute for Political Science at Justus Liebig University in Germany, tells NGW. There is some validity to both narratives, he says.

It was Moldova, after all, that sought changes to its long-term contract which left it more vulnerable to gas market volatility, he says. But at the same time, Russia is playing realpolitik, he argues.

“Russia withdrew its political support after the change in government, and was therefore less willing to offer a lower price,” he says. “Moscow doesn’t see a rationale for offering discounts to the new government when that new government has to an extent distanced itself from Russia.”

As for the breakdown in contract talks that led to an 11th hour, one-month extension, Yafimava says the reasons are unclear.

“Russia stood to win nothing from a gas standoff with Moldova, either commercially or in PR terms, as it was certain to result in yet more accusations of using gas as a weapon,” she says. “It seems much more likely that Moldova wanted (and may have been encouraged) to conclude only a short-term contract with Gazprom and not to accept its conditions…while hoping there would be a safety net provided should the negotiations fail. No such safety net materialised.”

One of those conditions, as stated in a protocol agreed by Moldova and Russia, is that an independent audit of Moldovagaz’s debt to Gazprom should be conducted in 2022 and then paid back over a five-year period. Secondly, the forced restructuring of Moldovagaz should not take place until the debt is paid. That debt is currently estimated at more than $700mn.

As a contracting member of the Energy Community, which helps aspiring EU members align their energy rules with the bloc’s Third Energy Package, Moldova is required to separate Moldovagaz’s transmission activities from its supply activities.

“It is easy to imagine that Gazprom’s concern over who will pay the debt once Moldovagaz’s unbundling is complete was construed as trying to force Moldova not to implement the EU acquis or undermining its government, thus giving rise to easy (and somewhat lazy) – but unconvincing – narratives of Russia having provoked the crisis to undermine Moldova’s new pro-European government,” Yafimava says.

She notes that both Sandu and Moldova’s deputy prime minister Andrei Spinu have said there were no political conditions attached to the new contract.

Moldova may have been counting on the EU to provide a safety net if talks with Gazprom failed. The bloc provided Moldova with €60mn ($68mn) of financial assistance “to set up a support scheme for the most vulnerable people”, but the EU’s foreign policy chief Josep Borell said on October 28 a solution to the country’s crisis would “not come from the European Union funding all the differences between the current prices and the prices Gazprom is asking for.” The following day Moldova and Russia signed their new long-term contract.

In any case, Russia wields substantial power over Moldova’s energy system. Not only does it control all its gas supply and the pipelines that it runs through, Russia’s state-owned Inter RAO also manages the power plant in Transnistria that delivers the majority of Moldova’s electricity.

Moldova now has access to Romanian gas via a pipeline that was completed last year. But it will prove a challenge to diversify Moldova’s energy supply until unbundling and other reforms have been implemented. Still, while the previous government was more content with maintaining the status quo, Cenusa says there is now political will in Chisinau for actively finding alternatives to Russian energy.

Moldovan gas reforms

The Energy Community, designed to help aspiring EU member states align their energy laws with the bloc’s Third Energy Package, released its latest implementation report in mid-November. In Moldova, the community’s secretariat said, implementation of the package “remains limited in practice.” It said the only positive development over the last year was the completion of the gas link with Romania, improving Moldova’s interconnectivity.

Moldova’s National Energy Regulatory Agency (ANRE) has transposed all relevant gas network codes, but they have not been implemented by Moldovatransgaz, the secretariat said. The network code on tariffs has similarly been transposed but not implemented. Amendments to the country’s gas law are being drafted to enable reforms, but the government has been inactive here throughout the period.

There is also no real progress on the unbundling of Moldova’s transmission system. ANRE rejected a request by Moldovatransgaz to be certified as an independent operator, and instead, the gas supply activities should be transferred to a newly set-up affiliate, Moldovagaz-Furnizare. No third party access is available, and backhaul supplies are still not offered by Moldovatransgaz. A contract was signed to launch a capacity booking platform, bringing Moldova in line with the Capacity Allocation Mechanism Network Code, but auctions did not take place by June 30 as planned. The balancing network code has not been implemented.

The secretariat said that Moldova’s wholesale gas market remained “illiquid and foreclosed,” while its retail market is still heavily regulated under a public service obligation scheme. Provisions on supply of last resort universally apply to all customers with adequate eligibility criteria, it said.