Mexico eyes LNG export future [Gas in Transition]

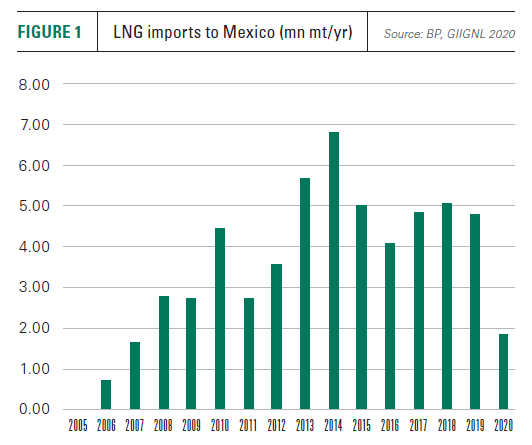

Mexican LNG imports slumped by over 60% in 2020 (Figure 1) to just 1.88mn metric tons, owing primarily to the economic contraction induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, one unparalleled since the Great Depression.

A rebound of sorts is expected in 2021, owing to forecast economic growth of 8.5%, a recourse to LNG spot purchases in the first quarter of the year during severe cold in Texas, which disrupted US pipeline gas exports, and the start-up of New Fortress Energy’s small-scale ISO-flex LNG import facility at the port of Pichilingue, Baja California Sur.

However, the long-term trajectory for Mexican LNG demand remains downward, owing to the development of US-Mexican cross border pipelines and the expansion of Mexico’s domestic gas network, which although often beset by delays and legal wrangles, is bringing pipeline gas to ever more parts of the country.

Moreover, the US has notably struggled to build LNG export capacity on its West Coast, which would offer shorter freight times to the dynamic and coal-dependent growth markets of Asia, avoiding both the charges for Panama Canal transits and the risks of canal congestion.

Highlighting the difficulties faced by developers in the US, one of the most promising west coast LNG plant proposals, the 7.5mn mt/yr Jordan Cove project in Oregon, was paused in April by Canadian developer Pembina Pipeline, owing to an inability to secure necessary permits.

LNG developers are looking to Mexico to fill the gap.

Import decline

Mexican LNG imports reached a peak in 2014 of 9.3bn m3 (6.8mn mt), but dropped the next year to 6.8bn m3 and then 5.6bn m3 in 2016 before stabilising at 6.5-7.0 bn m3/yr in 2017-2019. The decline in LNG imports reflected the expansion of US-Mexican cross border pipeline capacity and pipeline construction within Mexico, allowing US gas to reach further into the country.

The drop in imports to just 1.88mn mt in 2020 was the result of both the economic downturn and the first flow of gas through the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan gas pipeline in September 2019.

The drop in imports to just 1.88mn mt in 2020 was the result of both the economic downturn and the first flow of gas through the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan gas pipeline in September 2019.

The subsea pipeline runs down the northern part of Mexico’s east coast and is linked to the Agua Dulce gas hub in the US. It makes landfall at the Altamira LNG terminal and then again further south at Tuxpan, supplying gas to the Altamira V power plant, the 500mn ft3/d Monet Grande interconnect and the TC Energy Tamazunchale pipeline at Naranjos. Although flows remain substantially below nameplate capacity, the pipeline is designed to take 2.6bn ft3/d of gas.

An additional connection, the Jaltipan-Salina Cruz pipeline, has also been proposed as part of plans to bring gas to Mexico’s south-eastern states to address declining domestic production and foster industrial development in the region. The pipeline is to be built by state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidade.

As in the north, developers are considering using an expanded gas pipeline network to feed an LNG export facility, which would be located in Salina Cruz’s Pacific coast line.

Demand rising

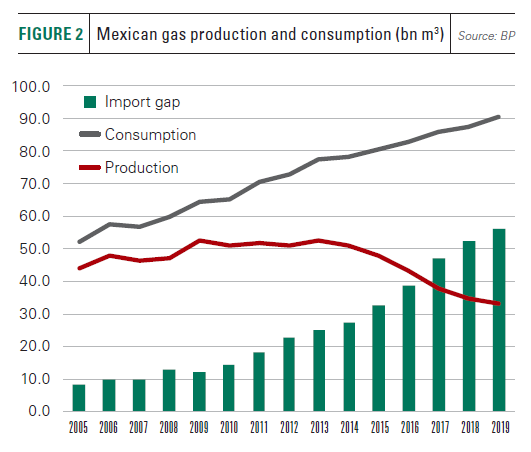

Mexican demand for imported gas has been on an exceptionally strong upward curve, driven both by rising consumption and falling domestic production, despite primary energy demand decreasing each year from 2018-2020.

Demand for gas, largely driven by the power sector but also increased city gas and industrial use, owing to access to cheap US shale gas, leapt from 66bn m3 in 2010 to 90.7bn m3 in 2019. Over the same period, domestic gas production (Figure 2) fell from 51.2bn m3 to 34.0 bn m3. The overall import gap has thus ballooned from 14.9bn m3 to 56.7bn m3 in the space of a decade.

The low cost of US gas has prompted the cash-strapped Mexican state oil company Pemex to focus on crude rather than gas production, which has led to shortages in regions of the country without pipeline access to the US border. This, in turn, has encouraged natural gas pipeline construction in the country.

As the US and Mexican economies rebound from the pandemic, energy consumption is expected to return to growth, driven not least by rapid population growth. According to the International Energy Agency, Mexico’s population is set to reach 150mn by 2050 up from 129mn today.

Gas has been well placed to benefit, owing to the country’s historic use of oil for power generation. Switching to gas offered a cheaper and cleaner alternative, while reduced power sector oil consumption helps to offset the country’s declining oil production.

Climate change concerns are also putting pressure on coal use in power generation, and, so far, growth in renewable energy output has been relatively modest, although declining costs and substantial wind and solar resources suggest renewables could play a much greater role in meeting electricity demand growth in the future.

Pipeline development

The extension of the Mexican pipeline network is the main threat to LNG imports. Sempra Energy’s Energia Costa Azul (ECA) LNG plant phase 1, located on Mexico’s west coast, is a brownfield conversion of a former LNG import facility, which became redundant as a result of abundant supplies of US shale gas on the US-Mexican border.

ECA phase 1 stood out as the only new LNG facility to receive a final investment decision in 2020. Now the company is proposing a second LNG plant to be located at Topolobampo in Sinaloa state. The facility, Vista Pacifico, would have capacity of 3-4mn mt/yr and would source feed gas from the El Encino Topolabampo pipeline, which is in turn linked to the US system via the Ojinaga-El Encino and Trans Pecos pipelines. Ojinaga-El Encino entered service in June 2017 and has capacity of 1.4bn ft3/d. Flows via the 1.4bn ft3/d Trans Pecos line remain well below capacity.

Sempra’s new proposal highlights how closely bound Mexico’s LNG imports and exports are to pipeline developments in both countries. According to Sempra, ECA phase 2 is currently not viable owing to a lack of appropriate US-Mexico pipeline capacity, but Vista Pacifico may be, if stranded gas in the Rockies can be accessed and transported by pipe across the border.

Even the prospects for Mexico’s busiest LNG import facility, the 3.2mn mt/yr Manzanillo LNG terminal, look precarious. Sited on the Pacific Coast in the central west region of the country, and completed in 2012, the facility originally bypassed a number of pipeline bottlenecks, allowing regasified LNG to reach the central region, which includes Mexico City, and where gas shortages were on the rise.

Relatively high throughput at Manzanillo has in large part been the result of technical problems on the Los Ramones Phase II South pipeline and slow completion of other projects. However, completion of the southern-most section of the Wahalajara system, a group of pipelines that connect west-central Mexico to the Waha gas hub in western Texas, last year, is expected to limit demand for Manzanillo LNG imports, as more customers are linked up to the new pipelines.

As a result, proposals have been made to convert the terminal into an LNG export facility. Like ECA, Mananzillo offers the attraction not just of its Pacific Coast location, but also brownfield conversion, making use of existing infrastructure to create a competitive investment option.

Infrastructural and political constraints

Despite the construction of new pipelines in Mexico, numerous bottlenecks remain and there is political opposition to the export of LNG, given the country’s growing demand for gas, declining domestic output and growing dependency on US gas. As new sources of demand for US pipeline imports within Mexico, LNG plants could push Mexican gas prices higher.

In addition to low flows on the Comanche Trail and Trans Pecos pipelines, both the Wahalajara and Texas-Tuxpan systems are operating at below 50% capacity because of bottlenecks on the pipelines they feed into, as well as reduced demand as a result of the pandemic.

Mexican President Andres Manual Lopez Obrador (AMLO) has held back on granting an LNG export permit to ECA phase 1, suggesting at different times last year that its approval should be linked to construction of a second plant at Topolabampo, or that Sempra should help alleviate gas surpluses in the northern Pacific coastal region, where electricity generation is largely based on fuel oil.

Since coming to office in 2018, AMLO has pushed a nationalist agenda designed to roll back the liberalising energy sector reforms of his predecessors.

Texas freeze

In February, severe cold weather in Texas resulted in the limitation of cross border gas supplies, resulting in power outages not just across Texas, but also in Mexico. Around 800 Mexican manufacturing facilities dependent on US gas imports were forced to suspend operations temporarily and millions of homes lost power.

AMLO used this to forward his aim of returning the electricity sector to state hands, a policy which potentially threatens assets owned by US and other foreign investors. The president’s policies have also stalled renewable energy sector projects, which would reduce the country’s growing dependence on imported US gas.

The freeze in Texas had other implications as it highlighted the importance of LNG import facilities in terms of energy security. Emergency spot LNG cargoes, benefiting from the proximity of US Gulf Coast LNG plants, were brought into the Altamira import terminal to alleviate the shortage of pipeline gas.

Mexico lacks sufficient gas storage capacity, which again underlines the security of supply benefits of the country’s remaining LNG import facilities. Mananzillo, owing to its Pacific Coast location, in addition offers easy access to non-US LNG supplies, for example from Peru or Pacific basin LNG producers.

However, the gradual completion of the country’s internal pipeline network, removal of bottlenecks and addition of users will expand access to cheap US gas. This suggests that Mexico’s use of LNG will decline to low levels based on Altamira and/or Mananzillo as strategic energy security assets with low utilisation, and small-scale systems, such as New Fortress Energy’s ISO-Flex terminal at Pichilingue servicing regions which the domestic pipeline system is unlikely to reach anytime soon.

|

Baja import solution With Mexico’s need for LNG increasingly supplanted by rising US pipeline gas imports, the opening of a new LNG import terminal may come as a surprise, but New Fortress Energy’s ISO-flex LNG import facility at the port of Pichilingue, is located on the Baja California Sur, which is almost entirely separated from central Mexico, and its gas pipeline network, by the Gulf of California. Construction of the 1.8 million gallon a day (2.1mn mt/yr) LNG terminal was announced in July 2019 at a cost of $192mn. The facility’s foundation contracts are to supply LNG to two open-cycle gas plants, CTG La Paz and CTG Baja California Sur. The contracts are for the supply of 250,000-500,000 gallons of LNG a day and were underwritten by a subsidiary of the state-owned Comisión Federal de Electricidad, which wants to replace fuel oil generation in the region with gas. CFE plans to build additional gas power plant capacity in the area. New Fortress Energy is also the developer of CTG La Paz and received three permits from Mexico’s energy regulator Comisión Reguladora de Energia in June covering regasification, storage and distribution of LNG. The permits allow LNG storage on a floating unit at Pichilingue and distribution in ISO-tanks with capacity of 40.5 m3. |