Mexico energy industry puzzled by fracking future [NGW Magazine]

Incoming Mexican president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador announced October 5 what many in the national energy industry feared: fracking for shale oil and gas will not be permitted during his six-year administration.

“Mexico is not going to use the famous method of fracking to produce oil and gas,” Lopez Obrador, known as Amlo, told reporters in the central Mexican state of San Luís Potosi. “This applies to the whole country. Let it be clear: during my six-year term fracking will not be utilised while we are in government.”

Not quite two weeks later, on October 17, Amlo doubled down against any near-term prospects for unconventional gas development by telling reporters at a news conference in Tamaulipas state that future oil and gas bid rounds would be suspended until 107 contracts awarded through rounds under the current administration begin producing.

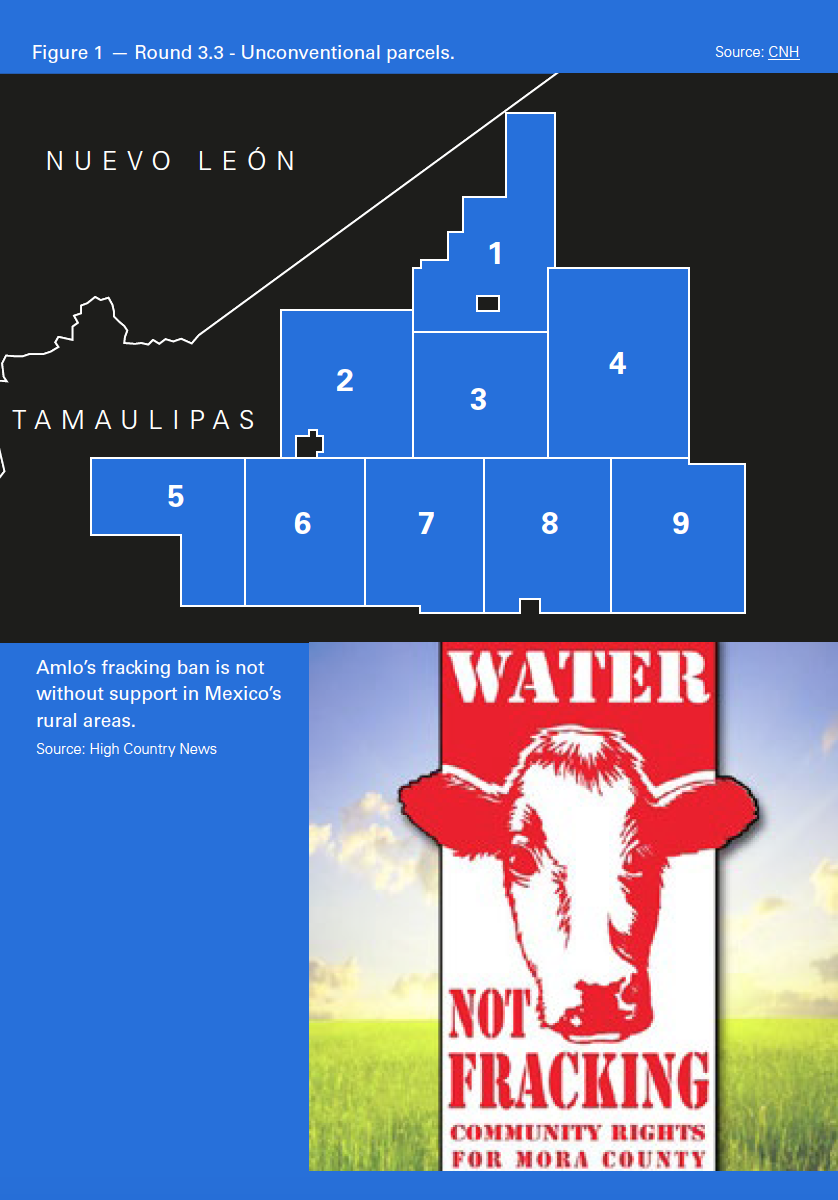

That announcement virtually confirms that Mexico’s next two bid rounds – Round 3.2 for 37 onshore conventional parcels, more than half in the Burgos basin, and Round 3.3, offering nine onshore unconventional parcels – set for February 2019 will not be held.

But Amlo also appeared to retreat slightly from his statements that fracking would not be allowed during his administration. Those words, he told reporters at the Tamaulipas news conference, were meant as a “non-binding” invitation for companies not to use the technique. And he reiterated previous assurances that his government would respect the validity of the contracts already awarded, some of which would potentially employ fracking technologies.

The decision to ban fracking, which Amlo repeated throughout October during visits to other regions of the country, rattled the Mexican energy industry. Production of shale oil and particularly shale gas was seen as a possible solution to the country’s declining natural gas production, which has required record high imports from the US to meet growing national demand.

By denying development of shale oil and gas through hydraulic fracking, the country will be forced to revise its long-term energy plans, Rosanety Barrios, manager of the industrial transformation policy unit at Sener, Mexico’s energy ministry, said at the Latin American & Caribbean Gas Conference in Mexico City on October 10. Mexico has been counting on the development of shale oil and gas in some of the country’s massive untapped basins, such as the Burgos and Tampico-Misantla, to reverse sagging output. If fracking is prohibited, Mexico is left with limited alternatives to boost natural gas production, Barrios said.

“Without question, the most important challenge in the natural gas market in Mexico is the development of methods to increase production,” Barrios said. “The only way to meet increasing demand for natural gas in our country is through imports from the US. If options for natural gas development are restricted, there will likely be more reliance on imports during the next administration.”

Defense of Fracking

Following Amlo’s declaration to prohibit fracking, Mexican politicians, business interest groups and members of the energy industry came out in defence of the practice, which they feel is misunderstood and unfairly characterised as destructive by the incoming president.

The first to voice opposition to the fracking ban was former Mexican president Vicente Fox. Known for being outspoken and opinionated, Fox said in an interview with Mexico City-based Radio Formula that a ban on fracking would be an “immeasurable error… We have a tremendous wealth of resources in the north of the country.” The natural gas basins in northern Mexico are near the border with the US and its Eagle Ford shale. “It isn’t true that fracking is destructive. It can generate wealth and protect the environment. Yes, it does consume water, but current technology allows for it to be recycled and reused. It shocks me that Lopez Obrador doesn’t know that.”

Fox said that the ban on fracking limits economic development in northern Mexico and other areas of the country where basins containing large prospective shale resources are located. The Burgos basin, which sits just south of the prolific Eagle Ford play in the US, and the eastern Tampico-Misantla basin near the Gulf of Mexico, are largely untapped and thought to hold massive shale gas reserves. Mexico has the sixth largest accumulation of shale gas reserves in the world, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

Gift for Texas Producers

Days later, in comments to the Mexican congress on October 11, energy minister Pedro Joaquin Coldwell said that fracking has been done in the country since 1960, adding that “22% of the wells that have been developed in conventional discoveries have used fracking in some form.” The country’s 2014 energy overhaul created regulation so that fracking would be done with the best environmental and industrial practices, he said.

“I would lament the day that an initiative is approved to prohibit fracking in our country. It would be an error,” Coldwell told members of Congress. “That day, Texas would have a party for the gift we are giving them because it would condemn us to continue importing gas – 53% of our gas reserves are precisely in unconventional resources and we can only extract them with hydraulic fracturing.”

Coldwell’s comments in support of fracking were echoed by Pemex CEO Carlos Trevino, congressman and former CEO of the Federal Electricity Commission Enrique Ochoa, National Hydrocarbons Commissioner Hector Moreira, several industry lawyers and Juan Pablo Castanon, president of the Mexican Business Chamber.

“The announcement that there won’t be fracking is bad news for the supply of natural gas,” Castanon said during an October 8 business conference in Mexico City. “We have to start to produce more gas and with prices competitive to those offered in Texas, where 60% of the gas that we consume is produced by fracking.”

Other voices in the industry think fracking, despite being a relatively new technology, has been demonised by the incoming administration for the potential environmental impact. In an October 10 panel at Mexico City gas conference, Veronica Irastorza, associate director at NERA Economic Consulting, said simply the use of the term “fracking” is considered almost a swear word in some parts of Latin America.

But an information campaign detailing how fracking works could assist the Mexican population to better understand the technology and the benefits shale gas development could bring to the national economy, according to Rodrigo Rosas, Mexico City-based gas analyst at Wood Mackenzie.

“It would be beneficial for the people of Mexico to better understand what fracking is and how it works prior to deciding that they are against it,” he told NGW on the sidelines of the conference. “We forecast that fracking would allow the development 6 trillion ft³ of natural gas in Mexico. If fracking is prohibited, those resources wouldn’t be produced and [it] would mean considerably more dependence on the US for imports.”

Finger-wag

Despite the chorus of voices pleading for Lopez Obrador to reconsider his stance on unconventional hydrocarbon development in Mexico, it appears the incoming president is committed to the ban. While Amlo has always said he wants to rescue the suffering hydrocarbon industry, he is resolute that it won’t be done through shale resource production.

“We don’t need fracking to extract oil or gas, we can produce oil and gas with techniques that won’t affect aquifers and destroy the environment,” he said October 12 in response to energy minister Coldwell’s comments the previous day. “I know that it is a polemic subject, but we have to take care of the environment and we have to consider the long-term impacts for future generations.”

A week later, on October 18, Amlo visited the northern state of Coahuila and met with local governor Miguel Angel Riquelme. Coahuila shares an international border with Texas and is home to basins containing large prospective shale oil and gas reserves.

In a press conference after his meeting with the governor – only a day after his Tamaulipas news conference at which he appeared to walk-back his plan to ban fracking – a reporter shouted out: “Is fracking going to happen, or not?”

Standing in front of the government offices in the state capital of Saltillo, Amlo smirked and wagged his finger back and forth. “Not going to happen,” he said. “As my finger indicates, it’s not going to happen.”