LNG stuck in the slow lane [NGW Magazine]

Mulling its role in a global low-emissions energy system, the gas industry is eyeing any and every opportunity. Powering more of the world’s shipping with LNG sits high on that list, but development is stuck in the slow lane. A panel at Gastech in Barcelona struggled on September 19 to find out why.

In LNG’s corner are drastic new emissions limits imposed on the maritime industry with a tight timeline. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) announced in October 2016 it will limit the sulphur content of marine fuel to 0.5% from January 1 2020, a checkpoint towards a bid to halve carbon emissions by 2050. The IMO now caps sulphur content globally at 3.5%, but a cap of 0.1% sulphur already exists in northern Europe, around North America, Hawaii and much of the Caribbean. This will remain unaffected by 2020 change.

Norway starting 2000, followed by the rest of Scandinavia, pioneered LNG as a bunker fuel.

The haste to comply with a global 0.5% cap is needed. According to presentations by the panel, commercial shipping produces 1m metric tons/day of CO2 and emissions from maritime will soon surpass that from land-based transport. It’s claimed that switching to LNG could cut nitrogen oxide and sulphur oxide emissions by over 90%; those two gases and particulates, common in oil products, are particularly damaging to human health

“There are 55,000 ships of over 500 mt,” said moderator Mark Bell, general manager of the Society for Gas as a Marine Fuel (SGMF). “Across that world fleet, around 0.2% – or 140 ships – are now running on LNG. A reasonable target appears to be to boost that to 2%, or 1,500 ships in the coming years.”

While that may not sound hugely ambitious, it would see annual demand from the shipping industry for LNG rise to match that of Japan, Bell says. The world’s largest consumer now uses 80mn-90mn mt/year.

“It’s a huge opportunity,” Bell said before striking a note of caution. “The maritime industry is a notoriously slow adapter,” he said but the panel of ship operators did not promise change soon.

Chicken or egg?

“Part of it is simply organisations and ship owners becoming comfortable with the idea,” says Gareth Jones of Canadian utility Fortis BC. He notes his company is having success supplying local shipping operators such as ferry companies. “Globally it is slower,” he adds.

It’s little wonder that it’s easier to sell the LNG story to operators of smaller vessels that run short, regular routes. They can be served by localised bunkering hubs. But the picture is more complex on a global basis.

Infrastructure is key, and remains a case of chicken and egg.

That is the main reason that the giants that move containers around the globe are largely yet to be tempted. For the meantime, most are sticking to using scrubbers to clean the emissions from burning heavy marine fuel-oil or switching to low-sulphur versions.

There are also other competitors to LNG promising to help shipping companies reduce emissions. Biofuels and methanol are also bidding for their favours. “We’re also seeing some electric vessels,” adds Fernando Impuesto of Spanish TSO Enagas.

“The key is the availability of gas,” says John Hatley, Americas vice-president for Finland’s Wartsila Marine Solutions. “We’ve been building large gas engines since the 1990s. It’s proven tech, but the infrastructure has been an issue.”

The intercontinental giants need a global network of refuelling options.

“The logistics of fuel supply are much more difficult for containers,” says Joaquin Mendiluce of Spanish utility Naturgy. “They are going from the Americas, to Europe to Asia and want to negotiate contracts that run across all those territories.”

But someone has to go first. “The infrastructure is needed to attract demand,” says Jones. “But to invest in infrastructure we need to prove clear customer demand.”

Oil, gas and maritime giants are starting to make efforts to break this conundrum, as they seek to provide both supply and demand to get the ball rolling. The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA), the world’s largest bunkering hub, is co-funding eight new LNG-fuelled ships.

On October 4, Shell announced its LNG bunker vessel Cardissa had performed its first ship-to-ship refuelling. Although owned by Russia’s Sovcomflot, the recipient - the Gagarin Prospect, the world’s first LNG-powered Aframax oil tanker - is on long-term lease to Shell.

Time and space

The chicken or egg puzzle is not the only familiar riddle. The issues of pricing and liquidity surrounding the evolution of the spot market are as much an issue for maritime customers as anyone. But there are additional obstacles specific to large and long-range shipping fleets that may not be so obvious to LNG suitors.

The length of service for a modern ship, and the huge investment costs of adapting or replacing them, are a very real issue. The world’s oceans are populated by thousands of ships that have an awful lot of useful life left in them, and the economics of replacing engines and fuel systems, rather than fitting scrubbers or adapting to lower emission fuel oils, often do not add up.

“New LNG-powered ships are more profitable” than vessels that run on fuel-oil, claims Mendiluce. “But retro fits often don’t make sense. With ships lasting 30 years or more that is clearly an obstacle to take-up.”

Perhaps even more crucial is the simple fact that LNG takes up more space than oil. Volume is a serious issue on what is essentially a toppled skyscraper making its way around the globe.

“The size of LNG storage is double that of fuel-oil and that makes it a real issue for designers,” Mendiluce adds.

At the end of the day though, there may be an even simpler reason behind the sluggish uptake of LNG by maritime. Estimates suggest compliance with the sulphur cap will cost the global shipping industry $60bn/yr, while the panel appeared to shrug off the risk of serious consequences for operators that do not meet the 2020 limits.

“The shipping industry is assuming it won’t happen by 2020,” says Jones, “but in a five-year window.”

Still, although progress is slower than hoped, confidence is high that LNG will end up fuelling a major chunk of the global fleet. DNV GL, a risk manager for the maritime and energy industries, forecasts that at least 30% of the world’s commercial ships will be powered by LNG in 2050.

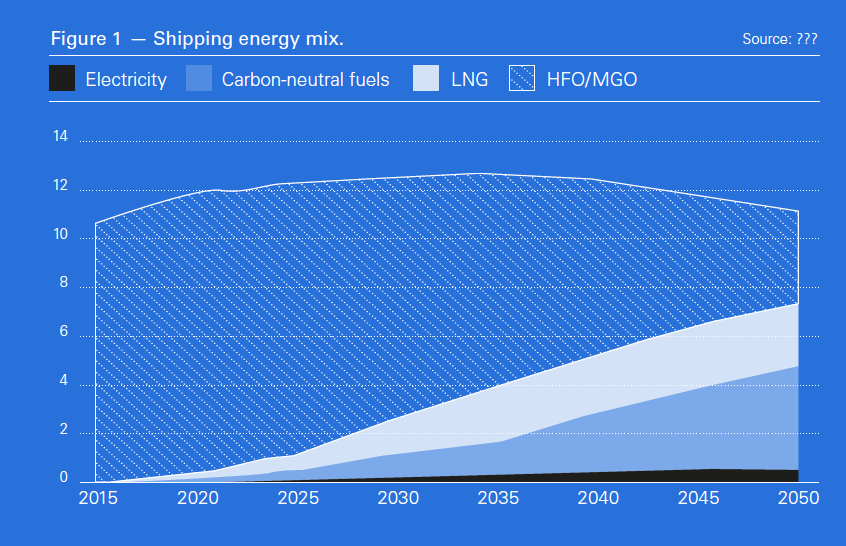

An article about DNV GL’s latest ‘Maritime Forecast to 2050’ forecast of the marine fuel mix out to 2050 was published on p47 of NGW Magazine, Issue 17 on September 17 this year. It forecasts that LNG use as a ship’s fuel will grow steeply to reach 23% of the bunker mix by 2050 (see graphic below) – which though is less than the forecast 32% in its year ago report.

The competition is starting to struggle to deal with the demands of environmental protection. Wartsila, one of the world’s leading suppliers of scrubbers, recently warned it cannot keep pace with demand.

“The infrastructure issues persist,” Mendiluce admits, “but the shipping companies are still ready to look closely at how LNG will affect profitability when the container fleet is being renewed”.

The gas industry must work to help them make the ‘right’ choice adds Impuesto. “Gas companies need to facilitate the decision of ship owners. We’re trying to go into a market with specific rules, which has contracts on the table. We must invest and must find ways to adapt our risk profile to deal with this new model. We’re in a different market; we have to know it.”

Refiners and shippers not ready: Rystad

Neither the refining nor shipping industries are prepared for IMO’s introduction of the global 0.5% sulphur cap, Rystad Energy’s head of oil market research Bjornar Tonhaugen told a conference it hosted in London October 4. “The economics are favourable to installing scrubbers, but many will cheat and run high-sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) without a scrubber” which from 2020 will be banned under IMO rules.

“Shipping fleets in Russia and China are likely to cheat,” he said.

Despite this, most will scramble to comply with the new IMO standards, and so global demand for diesel and marine gasoil will rise and will drive oil prices in 2019, Tonhaugen added. The increased call for diesel/MGO in 2020 would be 1.64mn b/d, which in turn would require higher crude runs at refineries – leading to a global oversupply of gas liquids, but tight crude supply and “a very tight gasoil supply” although he said that effect would fade over time in the 2020s.

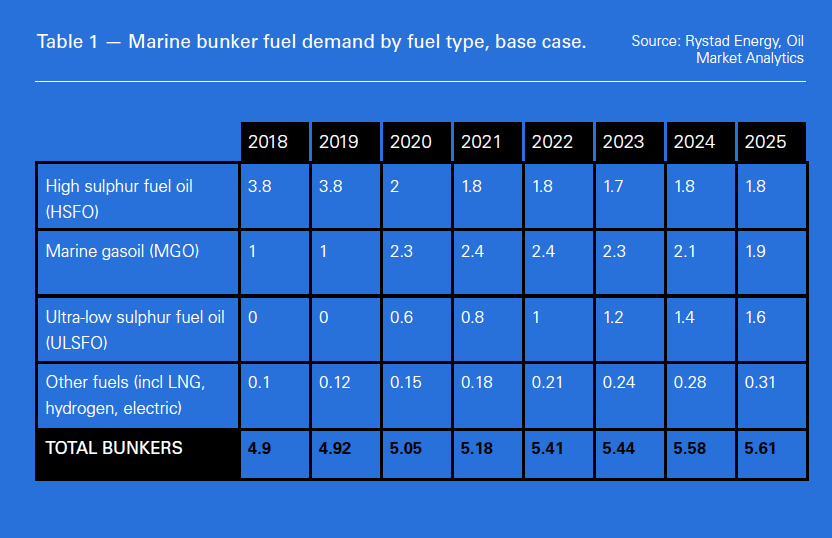

In order to meet the new fuel standards, the bunker demand mix will need to comprise “a bit of everything.” Most notably, he forecast that HSFO demand of 3.8mn b/d in 2018 and 2019 would shrink to 2mn b/d in 2020 and 1.8mn b/d in 2021-22, as use of HSFO by vessels without scrubbers would be banned. The extra demand would largely be met over time by ultra-low and standard marine gasoils, with ‘other fuels’ such as LNG, hydrogen and electricity expanding, albeit from a small base, the Rystad oil research chief added.