LNG sole option for Nigerian gas exports [Gas in Transition]

On January 16, Anglo-Dutch oil major Shell followed through on its plan to exit oil production in the Niger Delta by announcing that it had agreed to sell its Nigerian onshore subsidiary, Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria (SPDC), to the Renaissance consortium for $1.3bn, with the entire deal valued at $2.8bn. Renaissance comprises four Nigerian upstream companies, ND Western, Aradel Energy, First E&P and Waltersmith, plus Africa-focused investor Petrolin.

The deal must still be approved by Abuja. SPDC holds a 30% stake in the SPDC Joint Venture, alongside the state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) (55%), Total E&P Nigeria (10%) and Nigeria Agip Oil Company (5%). US oil major ExxonMobil, Norway’s Equinor and Italy’s Eni have all sold assets in the region in recent years.

Shell said that it would continue to play a role in supporting SPDC in the development and production of natural gas for the supply of feedstock to Nigeria LNG (NLNG) and retain both its stake in NLNG and its Nigerian deepwater operations. It will also provide technical expertise to SPDC “to support gas production and oversee delivery of key gas development projects”, it said.

Enduring onshore insecurity

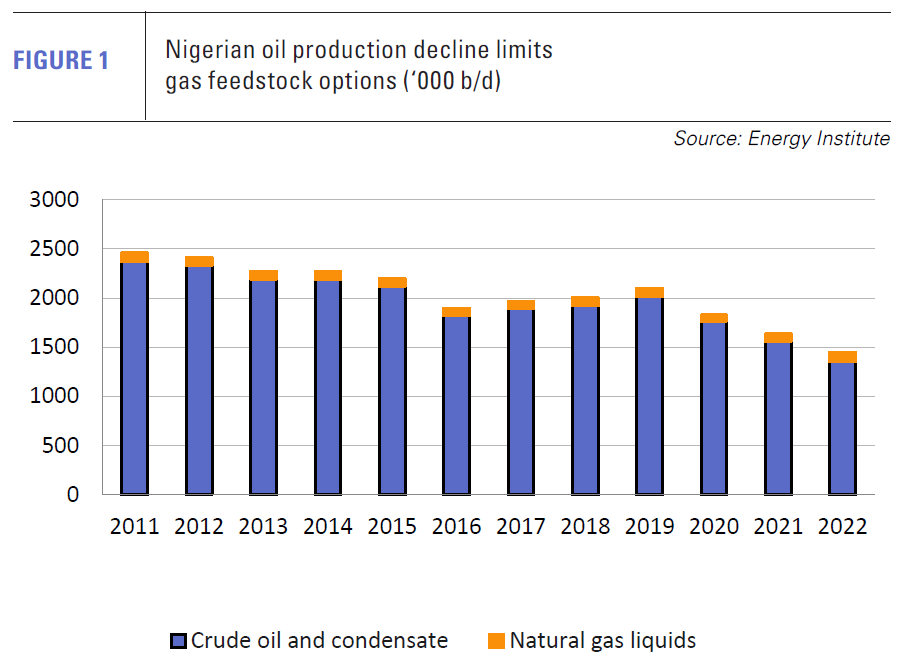

Nigeria has long struggled to make the most of its oil and gas reserves, owing to a combination of militant activity, pipeline sabotage and crude theft, which have led to chronic underinvestment. Oil production is currently half what it was in 2010 (see figure 1). Shell has also faced a series of lawsuits relating to the impact of oil spills which the company blames on militant activity, but for which it has been heavily criticised by many environmental and human rights groups.

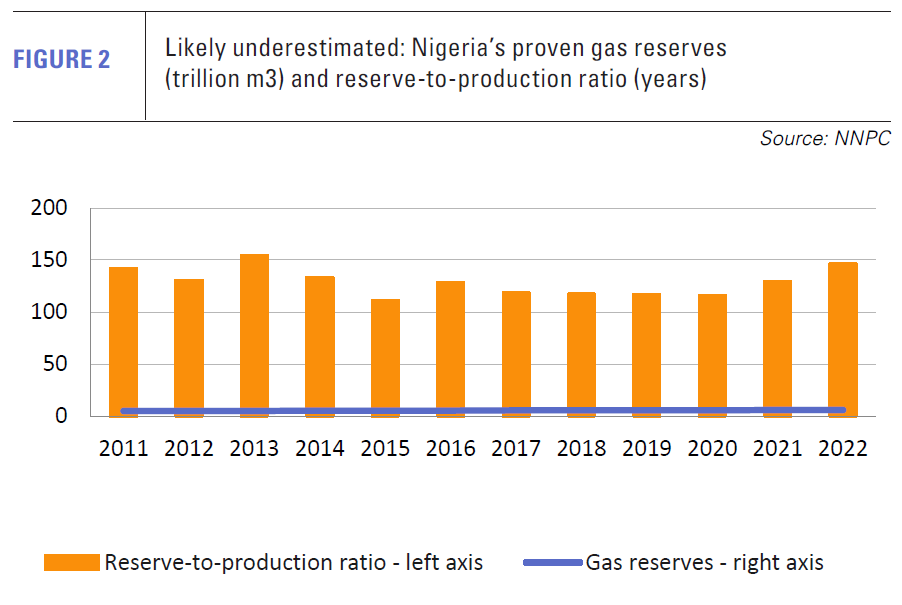

With 5.91 trillion m3 of proved gas reserves (see figure 2), Nigeria has the potential to increase substantially domestic gas supply and exports of both piped gas and LNG. The poor security situation and low domestic gas prices deterred upstream companies from appraising discoveries that were considered to be mainly natural gas for many years, so Nigeria’s actual gas reserves could be substantially larger than the official figure.

Some militants have claimed that the international oil companies that previously dominated the country’s hydrocarbon sector did not have the country’s best interests at heart, calling instead for much greater Nigerian control of the industry. However, it seems unlikely that attacks on pipelines and other oil industry infrastructure will decline as a result of the SPDC deal, not least because many of the attacks are associated with oil theft rather than political aspirations.

Nonetheless, Nigerian oil companies generally have few assets elsewhere and should be motivated to focus on increasing output. There have been reports in Nigeria that local companies, such as Heritage and Seplat, have been successful in boosting production from newly acquired assets.

NLNG plant

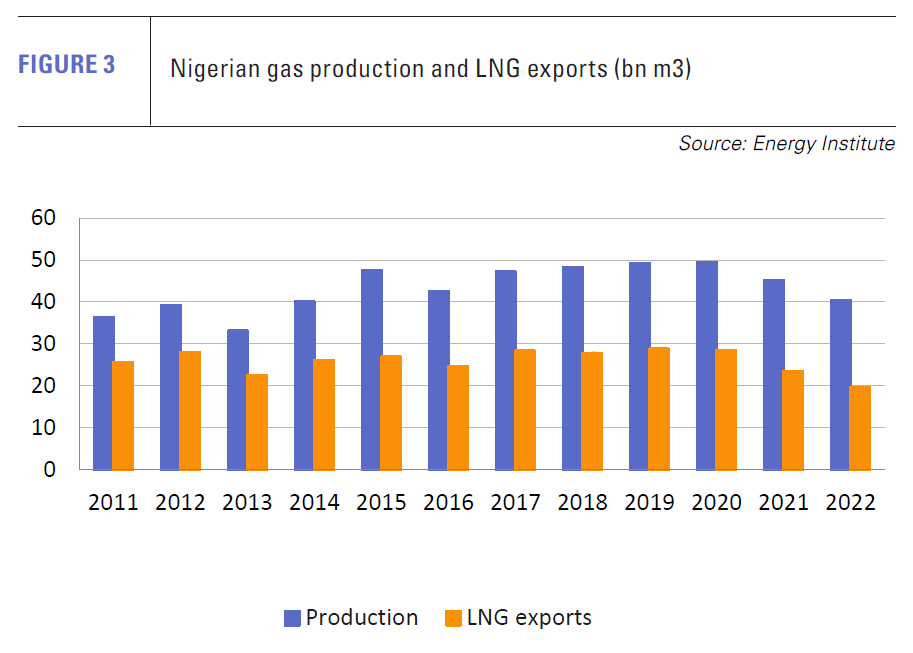

Investment in gas production is badly needed to maintain supplies to the NLNG plant on Bonny Island (see figure 3). The project has six trains with combined capacity of 22mn t/yr, but another 8mn t/yr will be added when Train 7 is completed by a consortium of South Korea’s Daewoo Engineering & Construction, Italy’s Saipem and Chiyoda of Japan. Work has been delayed by COVID-19 restrictions, disputes with local communities and gas supply problems. Statements by NLNG now suggest that the train could come on stream in 2027.

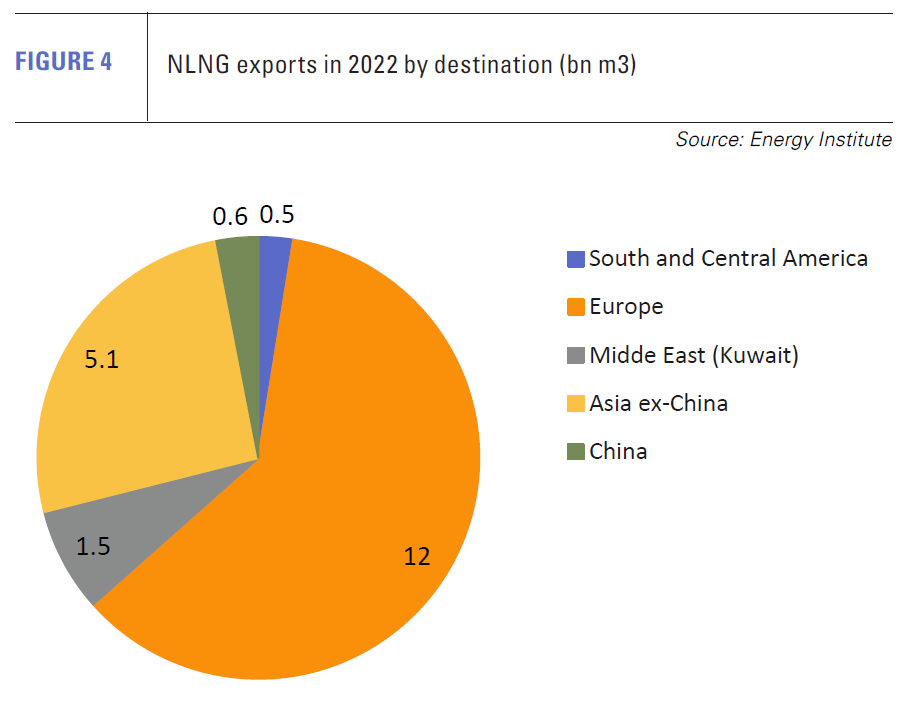

The company should have little difficulty securing sale and purchase contracts for the new train given Europe’s need to make up for the piped gas lost as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nigeria’s geographical location means that it is well placed to supply customers in both Europe and Asia along shipping routes unaffected by security threats in the approaches to the Red Sea (see figure 4). NLNG accounted for 7% of European LNG supply in 2022.

However, whether NLNG will be able to honour sales agreements is another matter. In October, NLNG Managing Director and CEO Philip Mshelbila said work on Train 7 was about 50% complete and that “NLNG was also looking to the future for further expansion with more trains, which would act as catalysts for the continued advancement of the gas sector”.

However, NLNG declared force majeure on its existing sales agreements in October 2022 following widespread flooding, leading to a shut-in of gas production. The company has maintained the force majeure since then, owing to a continued lack of feed gas.

Production has continued, but at a significantly lower level. Although the final figure for 2023 has not yet been released, NLNG confirmed in November that the plant was operating at below 50% capacity. S&P Global reported that 12.5mn tonnes had been shipped by early November 2023.

The company is seeking to source gas from new suppliers, but it is not clear if new pipelines are required to achieve this. With NLNG unable to source sufficient feed gas for its existing capacity, whether it will be able to operate a seventh train, let alone more, is an obvious concern.

Government support for FLNG

Aside from NLNG, about a dozen other LNG projects have been proposed in Nigeria over the past 15 years, but none have been built, partly as a result of the level of finance needed by the smaller companies seeking to build them, but particularly because of the gas supply problems linked to pipeline attacks.

Speaking at the Gastech conference in Singapore in September, Nigeria’s Minister of State for Gas, Ekperikpe Ekpo, said that the country could produce 57bn m3/yr of natural gas by 2030. Successive governments of both main Nigerian parties have made similarly ambitious claims over the past 20 years to little effect. The country’s gas output actually fell from 49bn m3 in 2020 to 40.4bn m3 in 2022. LNG exports dropped 16% to 19.6bn m3 over the same period.

The position of President Bola Tinubu, who came to power in May 2023, is a little uncertain as he has promised both to phase out fossil fuels and support investment in the oil and gas sector.

However, in July 2023, he offered to help the developers of Nigeria’s first planned floating LNG (FLNG) project to overcome any bottlenecks to development. The project is to be built by Nigerian firm UTM Offshore with production capacity of 1.2mn t/yr of LNG for export and 300,000 t/yr of LPG for the domestic market.

Engineering studies on the project are being undertaken by JGC, KBR and Technip Energies, with gas to be supplied from the offshore Yoho field on OML 104 block, which is currently operated by ExxonMobil. UTM hopes to take the final investment decision before the end of the first quarter 2024, with first production by the end of 2026. Trading house Vitol has been mooted as a likely customer.

Following agreements last year, the project consortium now comprises UTM Offshore (72%), NNPC (20%) and the government of Delta State (8%). Delta state holds about 40% of Nigeria’s proven gas reserves. Afreximbank has signed a preliminary deal with the developers to help finance the project, while a memorandum of understanding was signed with Golar in April 2023 to supply an FLNG vessel.

No piped alternative

LNG appears to be Nigeria’s best bet for increasing exports and monetising a larger portion of its gas reserves. The prospect of exporting gas to Europe by pipeline seems as far away as ever. The Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline to transport gas 4,128 km from Warri in the Niger Delta through Nigeria and across desert areas of Niger to Hassi R’Mel in Algeria has been on the drawing board since 2002. However, insecurity in the Sahara, coupled with Nigeria’s own militant activity and the scale of financing required have meant that it has never been developed.

Interest in building it resurfaced following the war in Ukraine, with the governments involved signing a preliminary agreement to build a line with 30bn m3/yr capacity. However, a coup in Niger in July 2023, the imposition of sanctions on the new military government by the rest of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and then Niger’s decision to leave Ecowas at the end of January 2024, makes the project a non-starter for the foreseeable future.

An alternative proposal involves extending the existing West Africa Gas Pipeline along the West African coast. However, this would be substantially longer, the capital cost consequently higher, and the pipeline would pass through 13 countries, making it much more difficult to negotiate, no matter how much gas Europe is prepared to buy.