LNG: it’s all about Asia [LNG Condensed]

Asia will increase its already dominant position on the buy side of the international LNG market over the next five years, according to a new report published by the International Energy Agency. One of the key determinants of how much its share of global demand increases will be the future level of Asian gas production. This is likely to be held in check by unencouraging domestic regulation and a lack of large conventional gas prospects, although coal gas is a potential threat, if environmental considerations are overridden.

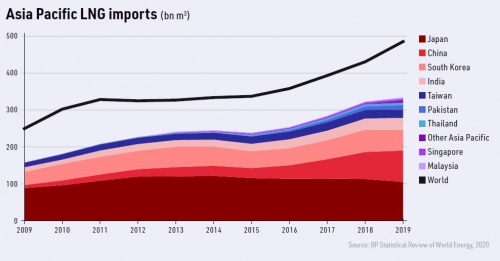

According to Gas 2020, published in June by the International Energy Agency (IEA), global LNG demand will increase by 21% between 2019 and 2025, reaching 585bn m3 in the latter year. Over the same period, the IEA projects that Asia Pacific’s share of global demand will increase from 69% to 77%.

The biggest question mark over future Asian LNG requirements is how much gas demand grows. This in turn will depend on the level and location of regional economic growth, both of which remain profoundly uncertain as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, supply-side factors will also affect Asian LNG requirements. These include inter-fuel competition. For instance, the IEA projects that Japanese LNG demand will fall from 105bn m3 in 2019 to about 95bn m3 in 2025 as nuclear plants re-enter service and renewable capacity increases against a background of sluggish electricity demand growth. Similarly, South Korean LNG demand is projected to fall from 2019 to 2025 as new nuclear and coal-fired capacity enters service.

LNG will also face competition from cross-border pipeline gas, although it is uncertain how much piped gas China will import in the medium to long term from Russia and Central Asia. The prospects for pipeline imports into South Asia from Turkmenistan, Iran and elsewhere also remain uncertain.

But, above all, indigenous gas output will be the key factor. In many Asian countries there is renewed emphasis on domestic energy production prompted by security of supply concerns, worries about the seeming fragility of international supply chains, and the urgent need to kick-start national economic activity by all means possible, including increased energy production.

Chinese output trends

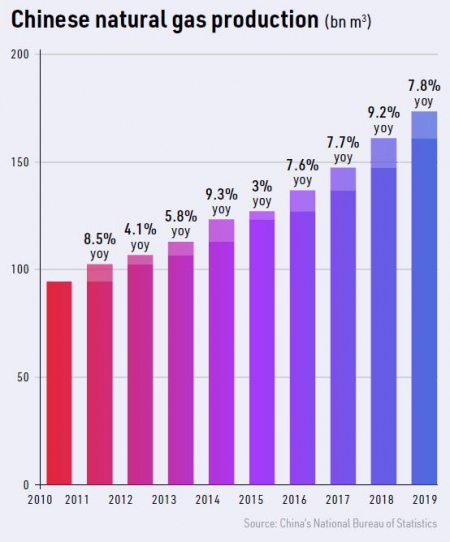

Chinese gas production lagged not only demand, but also official output targets. Production in 2020 will fall well short of the 207bn m3 targeted in the 13th Five-Year Plan. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, gas production in the first five months of 2020 was 78.81bn m3 -- up 8.7% year on year, but far below the level needed to achieve target.

Much of the shortfall occurred in the shale gas sector. The 13th Plan target for shale gas in 2020 was 30bn m3, but output in 2019 was only 15.5bn m3. This was a marked increase from 1.2bn m3 in 2014, but 2020 output will fall well short of target, itself under half the original goal of 60-100bn m3.

Looking forward, Beijing is not expected to release its official target for gas output in 2025 until the 14th Plan sectoral breakdowns are published, probably in 2021. However, the IEA estimates that Chinese gas output in 2025 will be 54bn m3 higher than in 2019 at over 230bn m3.

Bullish projections

The projected increase is not unprecedented -- output rose almost 56bn m3 between 2013 and 2019. Moreover, a large amount of investment has been poured into the sector since President Xi Jinping ordered state energy companies to boost output in August 2018.

The companies have since issued a series of bullish projections. CNPC said in 2019 it planned to double its Sichuan output to 50bn m3 by 2025. Meanwhile, PetroChina plans to produce 35bn m3 of shale gas in 2025, up from 8bn m3 in 2019.

But with little growth expected in conventional output many analysts are sceptical about China’s ability to produce large volumes of shale or other unconventional gas.

Some of the main constraints include fiscal and regulatory issues that could be rectified if the political will is there – changes to the shale gas taxation and subsidy regime have already boosted output. But there are also significant geological and technical constraints.

In August 2019, consultants Wood Mackenzie revised its projection of Chinese gas output in 2040 to 325bn m3, down 39bn m3 from its 2018 outlook because of a worsening prognosis for shale gas and CBM production. And, in July 2020, Norway’s Rystad Energy projected Chinese gas production would increase by under a fifth from 171bn m3 in 2019 to 203bn m3 in 2025, with most of the additional output being shale gas.

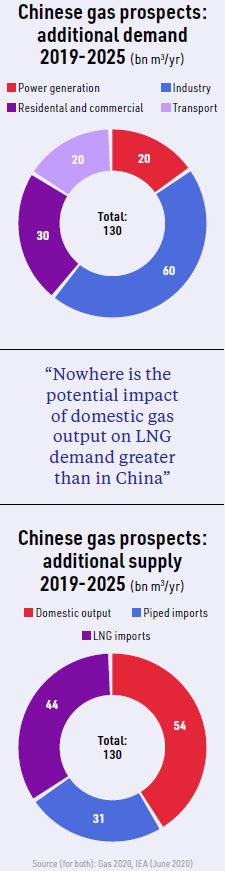

Even if the 54bn m3/year increase by 2025 is achieved, China would still require substantial gas imports. The IEA projects gas demand 130bn m3 higher in 2025 than 2019, driven by 60bn m3 of additional consumption in the industrial sector.

While Chinese gas production may not keep pace with demand in the next few years, it will at least grow. That is not the case in many Asian countries. Indeed, if China is excluded from the IEA’s projection of Asia Pacific output, it would actually fall by 15bn m3 between 2019 and 2025, to 622bn m3.

Indian growth potential

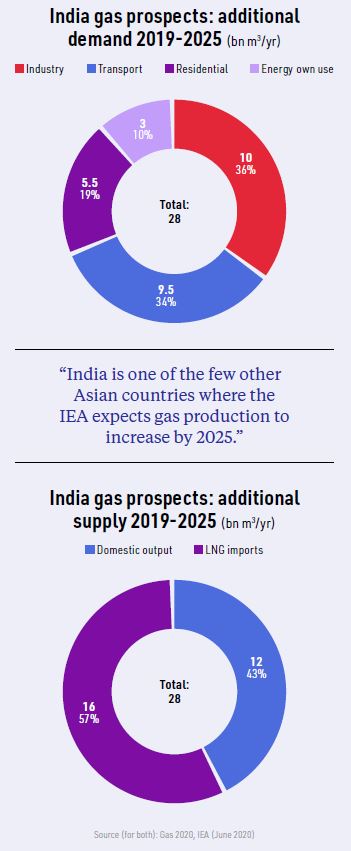

India is one of the few other Asian countries where the IEA expects gas production to increase by 2025. This would reverse a decade-long decline, which saw output fall from 47.4bn m3 in 2010 to 26.9bn m3 in 2019, according to BP’s data.

The decline is continuing, albeit in part due to India’s stringent lockdown. The 2.3bn m3 of gas produced in May was down 11.3% on target and 16% year on year, according to the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MPNG).

Achieving growth of this order would be difficult in a country where production has been hamstrung for years by fiscal, regulatory and technical problems. Some progress has been made on gas pricing and regulatory issues, but the sector remains dogged by problems, not least of them geological and technical. For instance, in November 2019, ONGC reduced projected FY2024 output at one of its key blocks -- KG-DWN-98/2 in the offshore Krishna Godavari basin – from 40bn m3 to 34bn m3 or lower.

Indian gas imports thus look set to continue growing, with the only option over the next five years at least being LNG. The IEA expects Indian LNG demand to increase by 16bn m3 from 2019 to 2025, rising from about 32bn m3 to 48bn m3.

South Asian reserves

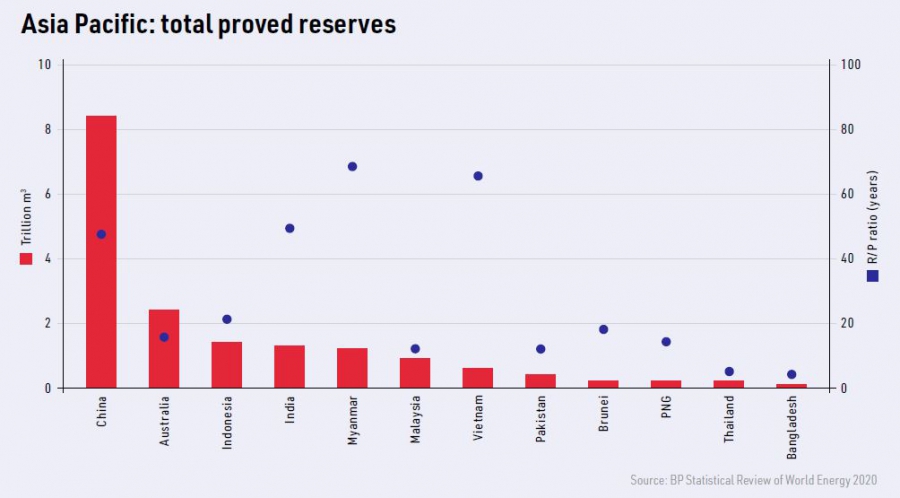

Other South Asian countries are also likely to remain reliant on LNG to meet growth. Gas production in Pakistan has been treading water at 34-37bn m3 for over a decade, while output in Bangladesh has remained at 26-29bn m3 since 2015.

Once again, regulatory and pricing problems are key factors. This has resulted in low spending on exploration, few new finds and stagnant production in both countries. As a result, gas demand growth has either been suppressed or satisfied by LNG. In 2019, Pakistan and Bangladesh imported 11.8bn m3 and 5.7bn m3 of LNG, respectively.

There is little likelihood that burgeoning gas demand in Pakistan will moderate or that domestic output will grow. Rather the reverse. The Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority has forecast output will fall from 34bn m3 in 2018 to under 18bn m3 in 2028, whereas demand in the latter year is projected at 86bn m3.

Bangladesh’s production currently comes from about 20 onshore fields, most of which are depleting fast, with the reserve to production (R/P) ratio in 2019 only 4.2. The focus is now on offshore resources, with areas of the Bay of Bengal appearing highly prospective.

However, offshore production is unlikely to begin before 2025, with near to medium-term demand growth likely to rely on additional LNG.

Southeast Asia

Thailand’s gas production peaked in 2014 and is soon expected to contract, with new output severely constrained by the cost and complexity of existing prospects. While gas demand has increased relatively slowly, concerns that Myanmar will export less gas has led Thailand to prioritise LNG imports. These rose from 1.9bn m3 in 2014 to 6.7bn m3 in 2019.

Vietnam is unusual in that, despite having one of the highest R/P ratios in Asia, it decided in 2017 to complement local production projected at up to 19bn m3 in 2025 with up to 4bn m3 of LNG imports. This was to meet the rapid growth planned in gas-fired generation. However, a new power development plan is under consideration which might reduce the need for gas -- and thus LNG imports -- because of the unexpectedly fast growth in renewable generation.

Coal gas threat

Overall, it seems probable that Asian gas production will grow only modestly, meaning LNG imports must increase unless there is a drastic slowdown in gas demand. Production in some countries will contract because of limited reserves of economically and technically-viable gas, while in others growth will be constrained by pricing and regulatory problems.

However, a less hostile policy environment, particularly in south Asia, could see output grow quickly. And while unconventional gas production has had a limited impact in Asia to date, there are circumstances in which it could grow more rapidly in the near to medium term.

One such circumstance is the possibility that production of gas from coal could take off. The potential is substantial in countries including China, India, Indonesia and Pakistan where coal is plentiful and low cost, but increasingly out of favour for direct use in power generation. In China, for instance, almost 80 projects with 300bn m3/year of capacity had been proposed by June 2020.

Coal-based synthetic gas would face strong environmental opposition and at current LNG prices the economics of many projects are unconvincing. However, given the increasing emphasis on national security of energy supply in China and elsewhere, these concerns may well be overridden to some extent, meaning it could become a significant source of supply and competition to LNG.

_f500x257_1596458071.JPG)