LNG demand depth is substantial, but hard to unlock [Gas in Transition]

According to a new report by the International Energy Forum (IEF), ten new importers are expected to join the international LNG market in the next two years, helping to drive a 25% expansion in global LNG trade to 500mn t/yr by 2028.

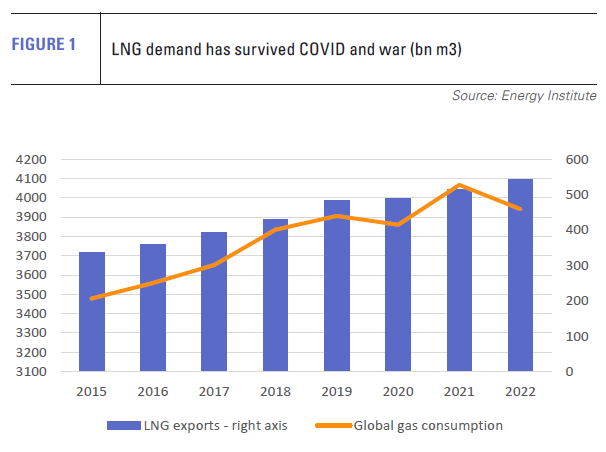

Over the period 2019-2022, LNG trade grew by 16% from 337mn t/yr to a record 390mn t/yr (see figure 1), owing, in particular, to the surge in European demand as a result of the war in Ukraine and loss of pipeline imports from Russia. Russian pipeline exports to the EU fell dramatically in 2022 by 55% from 141bn m3 to 64bn m3, and by a further 64% to just 40 bn m3 this year, the IEF says.

Demand forecasts highly uncertain for marginal markets

However, one of the most uncertain impacts of the Ukraine war and reconfiguration of international LNG trade flows has been the effect on future demand. High prices and a lack of availability have put many LNG import projects on hold, particularly in new and price-sensitive markets.

While the IEF report identifies numerous new market entrants as growth drivers in the near term, it also notes that a lack of affordable LNG has increased the risk of delay or cancellation for proposed LNG import projects in Asia and Africa. This, it says, “has increased uncertainty for long-term demand in the regions that the global LNG industry had been counting on for robust growth.”

On the import side, the report identifies 22mn t/yr of new regasification capacity, mainly in Asia and Africa from new market entrants. For Africa, Senegal, Ghana, Benin, Morocco, Sierra Leone and South Africa could all become LNG importers within the next three-four years, the report says.

Africa remains a highly uncertain LNG import market

Senegal – itself set to become an LNG exporter from early next year – is an example of the uncertainties governing many of these markets. It has a small Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU), developed and operated by a joint venture between Karpowership and Mitsui OSK Lines. It is designed to feed gas into a 236-MW Karpower power plant vessel. However, an inaugural cargo destined for the facility in May was rerouted to Brazil at the last minute.

Senegalese’s emergent LNG use is also at risk from growing political instability in the run-up to presidential elections in February. West Africa has seen a surge in political coups since 2021, leading to fears of ‘democratic regression’ across the region.

Ghana has faced similar delays and uncertainty. It’s 1.7mn t/yr LNG import terminal was originally supposed to come online in 2016, but commercial operations are not now expected until 2025. The government has built up substantial debts with Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and the sector’s ability to absorb imported LNG economically at present looks doubtful.

Ghana’s Tema LNG terminal project, in theory, was to act as an LNG storage hub, potentially facilitating LNG supplies to Burkina Faso, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Ghana’s Tema LNG terminal project, in theory, was to act as an LNG storage hub, potentially facilitating LNG supplies to Burkina Faso, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Benin, which has a project for 0.5mn t/yr import capacity, had targeted start-up in 2021, but there has been little news since, and some observers label the project as ‘shelved’. Equally, Sierra Leone’s pursuit of the Freetown LNG terminal project appears to have made little headway.

Even in South Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest economy, long-planned LNG import plans have struggled to come to fruition. Current plans seem to hang on two vessels owned by Karpower being converted to FSRUs. The ships would be used to regasify LNG to supply floating gas-fired generation.

Karpower won bids to supply two powerships with a total generation capacity of 770 MW under South Africa’s Risk Mitigation IPP Procurement Programme (RMIPPPP) in 2021. However, the company has since faced a series of legal challenges and the RMIPPPP has also suffered delays.

While Morocco has entered the LNG market, primarily to replace the loss of pipeline supplies from Algeria, LNG demand south of the Sahara Desert remains a very uncertain prospect. Even if the group of African countries identified by IEF do start to import LNG in the next three to four years, volumes are unlikely to be large and these markets will be price sensitive and carry significant credit risk.

Asia offers better prospects

IEF expects the Southeast Asian market to more than double to 40mn t/yr by 2030 as countries like the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand increase imports. In addition, Singapore is expected to add a second import terminal which will act as a hub to store, reload and break-bulk LNG, the report says, aiding the fuel’s uptake across the region.

The drivers behind these countries’ rising import prospects are a combination of declining or peaking domestic gas production, a desire to reduce their dependence on coal, and high rates of energy demand growth.

LNG prospects in Southeast Asia have been buoyed by the start of imports into both the Philippines and Vietnam this year, while Thai demand for LNG is on a strong upward trajectory.

However, Cambodia and Myanmar are much more uncertain. Since starting the import of LNG in ISO containers in 2020, little has been heard about the development of phases 2 and 3 of Cambodia’s LNG project, which promised a floating regasification terminal, gas pipeline and trucking network.

Similarly, relatively small-scale LNG operations in Myanmar – as in Cambodia, developed and supported by China – appear to have been scaled back in the aftermath of the country’s 2021 coup.

Local media in July reported the closure of two LNG-fed Chinese-developed power plants in western Myanmar and the closure of a third this year, owing to a lack of LNG. An offensive by rebel groups opposed to the ruling junta in recent months has further undermined confidence in the country’s investment climate. Political analysts say the uprising could not have taken place without the tacit approval of Beijing.

However, the plans overall suggest there is significant latent demand for LNG in both Asia and Africa, which would be much more likely to emerge in an environment of lower prices and more plentiful supply. Arguably, a prospective period of global market surplus in the late 2020s -- the result primarily of LNG export capacity expansion in the US and Qatar and a peaking of European LNG consumption -- would provide impetus to currently stalled plans for new LNG import markets.

Latent demand in China and Europe

A key part of the ‘looming surplus’ narrative is a decline in European LNG demand as it accelerates the construction of more renewable energy capacity. However, as recent commentary from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) suggests, European gas demand might also bounce back, if prices become more attractive. This would likely sustain the rise in LNG imports, as a return to Russian pipeline gas looks highly unlikely.

According to the OIES, European gas demand was down 10% year on year in the first ten months of 2023, but gas use in the industrial sector and small businesses started to recover in the third quarter. This recovery is likely to be capped in the short term by the poor outlook for the European economy, the report says, but it does suggest permanent demand destruction may have been limited.

According to the OIES, European gas demand was down 10% year on year in the first ten months of 2023, but gas use in the industrial sector and small businesses started to recover in the third quarter. This recovery is likely to be capped in the short term by the poor outlook for the European economy, the report says, but it does suggest permanent demand destruction may have been limited.

OIES says over half of the demand drop this year was accounted for in the first quarter, reflecting mild weather reducing electricity demand, limited industrial recovery and higher availability of renewable energy resources.

For next year, it says: “there are many moving pieces to the puzzle, but continued lower use of gas in power is expected to be counterbalanced by higher gas use in other sectors and could drive gas demand marginally up over the year.”

Similarly, in China, price moderation has been a key factor in returning the country to demand growth for LNG. Gas imports have increased each month since March, and from January to September, they were 8% higher than in 2022. Reports now suggest Chinese gas demand could grow this year by as much as 8% overall. State-owned oil company CNOOC forecast in September that the country’s LNG imports could rise by 10.9% year on year in 2023.

Demand suppressed not destroyed

The possibility of demand destruction as opposed to demand suppression as a result of the high prices induced by the war in Ukraine is arguably fairly weak. The alternatives to gas in the short term are typically other higher carbon fossil fuels, rather than electrification.

Decisions to limit production runs or use other fuels are likely to be reversed, if economic conditions brighten and prices fall. Industry is waiting out the period of high prices rather than retooling because the non-fossil fuel-based options are not yet sufficiently well developed or economically viable.

The loss of gas demand as a result of the energy transition remains somewhat further off, in the 2030s. Moreover, the rate of renewable energy construction remains significantly off target in all areas, except the deployment of solar power, while the required investment in grid expansion, on which much increased electrification increasingly depends, lags even further.

This suggests gas demand will bounce back in the major economies already using LNG, and that new markets will eventually be created, particularly if the second half of the 2020s does produce a glut of LNG and low prices. The Golden Age of Gas may have passed, but that doesn’t mean that LNG use has peaked – on the contrary, forecasts suggest continued market expansion well into the 2030s.