LNG bunkering industry defends fuel’s climate case [Gas in Transition]

Shipowners are in increasing numbers turning to LNG as a means of cutting emissions, with shipping services group Clarksons recently estimating that 30% of the new ships ordered this year in gross tonnage terms will be designed to run on the fuel. However, critics argue that the methane emissions that result from gas supply chains erode LNG’s climate benefits, and current record high gas prices may prompt more scrutiny of the fuel’s affordability..png)

LNG bunkering association SEA-LNG argues that LNG is the only commercially viable and scalable marine fuel that can keep shipping competitive while bringing about emissions savings. In a study commissioned by SEA-LNG in April, Sphera concluded that using LNG could reduce well-to-wake greenhouse gas emissions by up to 23% compared with the use of very low sulphur fuel oil, when two-stroke slow-speed engines are used. LNG also produces 21% lower emissions than marine gasoil when this engine type is used. Meanwhile, two-stroke slow-speed Otto engines achieve smaller reductions of only 14% versus very low sulphur fuel oil and 12% versus marine gasoil.

Besides lower CO2 emissions, LNG use also results in negligible emissions of sulphur oxides and particulate matter, and reduces nitrogen oxide emissions by 95% compared with oil-based fuels in use today. What is more, LNG can serve as a gateway for shipowners to adopt zero-emission fuels such as bio-LNG and synthetic LNG at a later point, without having to invest in new vessel equipment, SEA-LNG says.

“There will be a basket of fuels in the decades to come, but we think LNG and its bio and synthetic cousins will have a significant share of that basket,” Steve Esau, general manager at SEA-LNG, tells NGW..png)

Contrasting conclusions

There is still scepticism about the climate case for LNG bunkering, however, and other research has drawn very different conclusions about its ability to deliver emissions savings.

The World Bank concluded in a report, also published in April, that LNG should play only a limited role in decarbonising shipping, ruling it out as either a significant “temporary” fuel or a “transitionary” fuel. The bank urged countries not to provide additional support policies for LNG as a bunker fuel and consider removing existing ones. The bank meanwhile hailed ammonia and hydrogen as the most promising zero-carbon fuels.

SEA-LNG has criticised the World Bank for what it sees as an overly “prescriptive approach.”

“By focusing on theoretical, unproven solutions, the World Bank stifles innovation in technologies that can also provide answers in the decades ahead,” the association said at the time of the report’s release.

The data used by the World Bank to analyse the methane emissions associated with LNG bunkering value chains is “outdated,” Esau says. “And the report doesn’t recognise the transitional pathway through bio and synthetic LNG.”

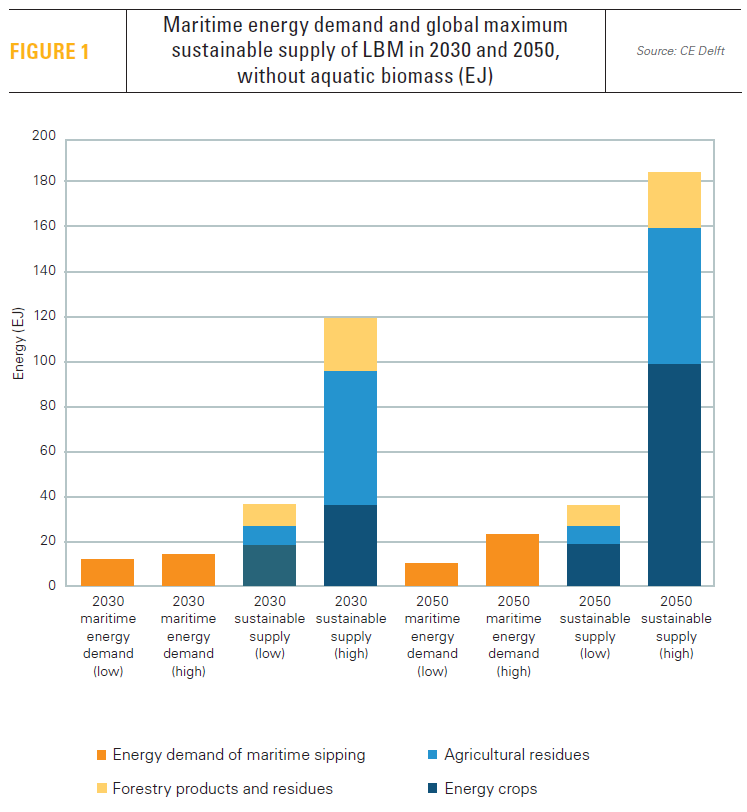

He also rejects the argument that future bio-LNG supply will be too limited and too expensive to make a dent in shipping emissions, pointing to research that SEA-LNG commissioned from Dutch environmental consultant CE Delft. In its report published last year, CE Delft concluded that even in low-case scenarios, the maximum conceivable bio-LNG production exceeds demand from the shipping industry in the coming decades (Figure 1). In the high-end scenario, supply exceeds maritime demand multiple times over.

.png) However, CE Delft cautions that “this analysis does not take into account that the actual production of biomass may be less than the maximum conceivable production, that not all biomass will be converted into methane and that there is competing demand from other sectors for methane.”

However, CE Delft cautions that “this analysis does not take into account that the actual production of biomass may be less than the maximum conceivable production, that not all biomass will be converted into methane and that there is competing demand from other sectors for methane.”

According to Esau, some of the studies that cast doubt on the climate case for LNG bunkering are based on out-of-date engine technologies, and predominately focus on low-pressure four-stroke engines which result in increased methane slip. There has been a fourfold decrease in methane emissions from the worst-performing engines in use over the last 15 years, he says, and methane slip is on track to be eliminated by 2030.

“Shipowners and subsequently engine manufacturers have clear commercial incentives to have more efficient engines, burning as much of those residual amounts of methane as possible,” he says. “You can already buy LNG-fuelled engines that effectively have no methane slip. You need the shipowners to buy those technologies.”

IMO steps in

The tougher rules imposed by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) on shipping pollution helped propel LNG to become a truly global shipping fuel. Previously, uptake of the fuel was mostly driven by local regulation on emissions.

LNG bunkering is most popular in Europe, where the European Commission recently published its Fit for 55 legislative package, designed to align laws with the bloc’s target of cutting emissions by 55% by 2030. Among many other measures, Fit for 55 proposes to include shipping in the emissions trading system, and this is expected to spur increased LNG adoption.

“The proposed package of legislation is broadly aligned with SEA-LNG’s position that goal-based and technology neutral policies are needed to ensure innovation and a level playing field for all low and zero-carbon marine fuels,” the association commented on the package.

With regulations on shipping pollutants due to become increasingly stringent in the coming years and decades, shipowners are looking to invest in future-proof fuel options. While there is no single solution for decarbonising the maritime industry, Esau says LNG provides “optionality.” LNG can be replaced with bio-LNG or synthetic LNG at a later stage without needing investment in new fuelling equipment. And many engines that run on LNG are also dual-fuel, capable of using diesel instead. This diesel can be replaced by biodiesel or synthetic diesel at a later stage.

“LNG provides a lot of optionality, which gives you a degree of insurance against regulatory flux,” Esau says.

The use of potentially zero-emissions fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen is still at a nascent stage of development. Beyond the technical challenges that these fuels present, infrastructure would have to be established on a global scale to deploy them in shipping.

Ammonia’s low flammability is also a challenge, Esau says, meaning that a lot of pilot fuel is needed to initiate the ignition. Usually this pilot fuel is diesel, presenting another issue for decarbonisation. Burning ammonia also creates nitrous oxides – a greenhouse gas many times more potent than methane – and so the emissions need to be cleaned up. Unburnt ammonia, given how toxic the chemical is, also needs to be handled.

There are also significant safety issues with hydrogen given its high flammability, and it has a low energy density, creating storage difficulties.

“We’re not saying that these technologies won’t happen, but we’re asking when they are actually going to be viable maritime fuels,” Esau says.

In the case of green hydrogen and green ammonia, there is also a question about the availability of renewable energy sources to power the needed electrolysers.

Esau dismisses that current high gas price will have a significant impact on shipowners’ decisions whether to order LNG-fuelled vessels.

“If you’re investing in a ship, you’re investing in an asset with a life of 20-30 years,” he says. “Clearly people will be influenced by the gas price today. But generally when they look at these things soberly, it is all about the long-term expectation for the fuel price.”

“Structurally, LNG has been significantly lower cost than oil on an energy equivalent basis for the past several decades,” he says.

|

A new player enters the LNG bunkering game While there are already many well-established LNG bunkerers active in Europe, new players continue to enter the sector. Russian oil company Gazprom Neft will shortly make its foray, having recently completed construction on what is Russia’s first ever LNG bunkering vessel. The traditionally oil-focused company is now shifting its attention towards natural gas, attracted by more robust growth prospects for the fuel. As part of this pivot, it wants to manoeuvre its existing experience as a major global bunkerer of oil-based marine fuels to provide LNG refuelling services. LNG has been used for ship propulsion for decades, but orders for LNG-fuelled vessels have soared since the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) imposed a stricter limit on sulphur content in shipping fuel in 2020. In Europe, the European Commission’s proposal to include shipping in the emissions trading system as part of its Fit for 55 legislative package is expected to drive further LNG adoption, given its lower CO2 emissions compared with conventional, oil-based fuels. Gazprom Neft announced in August that the Dmitry Mendeleev LNG bunkering barge, named after the famous Russian chemist, had been fully tested and would soon embark on its maiden voyage to the Baltic Sea. There it is expected to provide ship-to-ship bunkering services to passenger and cargo vessels at ports including St Petersburg, Ust-Luga, Primorsk, Kaliningrad and Vyborg. With a storage capacity of 5,800 m3, the vessel has an Arc4 ice-class reinforced hull that allows it to navigate through ice almost a metre thick. “LNG is now the optimum alternative to traditional marine fuel,” Alexei Medvedev, CEO of Gazprom Neft’s marine bunkering division, tells NGW, estimating that the fuel will account for a significant proportion of bunkering companies’ sales in the long term. The company has already concluded LNG bunkering agreements with a number of Russian and international customers, and continues talks with others, Medvedev says. One of its customers is a major LNG rail ferry operator working in the Baltic Sea, he says. The vessel will source its LNG from a small-scale liquefaction in Vysotsk in the Leningrad region, which is owned by Novatek. Moving forward, Gazprom Neft is considering the addition of two more LNG bunkering vessels to its fleet in the medium term, Medvedev says. It may decide to branch out into other areas of Russia, depending on LNG bunkering demand and availability of the gas, he says. Russia is now offering subsidies for the development of LNG bunkering infrastructure at its sea and river ports, as well as for equipping ships to run on the fuel. Local authorities are also engaging with equipment manufacturers and potential vessel purchasers to seek ways of scaling up gas-powered transport as soon as possible, Medvedev says. |