Kiev prioritises gas output [NGW Magazine]

A high-level delegation from Kiev, representing Ukrainian government, parliamentary and industry bodies launched the second round of oil and gas auctions in London January 29. The speakers were keen to reassure the audience that the rules were now fixed and that arbitrary hikes in royalties were a thing of the past.

All the licences are for exploration and production for a term of 20 years and investors will have 90 calendar days to view and submit a competitive bid. Over the year, Ukraine plans to offer more than 40 oil and gas blocks through online auctions, and also wants to sign production-sharing agreements (PSAs) with foreign entities and production enhancing contracts (PEC). The first round opened early December and the auction will take place 90 days later, March 6; while the second auction will take place April 29. The winner will be the highest bidder.

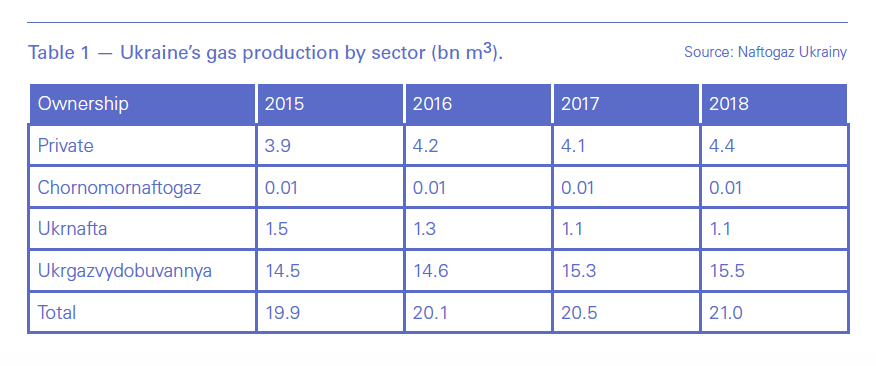

But is Ukraine now a place where it is safe to do business upstream, from a regulatory point of view? Emphatically yes, according to the Association of Ukrainian Gas Producers (AGPU). Things are also better upstream, with gas production rising since 2015 and now at 21.6bn m³/yr, with the potential for much more.

AGPU head Roman Opimakh said that the regulatory changes have made the country a much more attractive place to consider investing than it was even just half a year ago. The new production-sharing agreements that protect investors from changes in tax law, a faster permitting process and more access to historical data – free to those whose bids end up unsuccessful – have removed major obstacles that stood in the way of prospective producers, he told NGW.

Opimakh hopes the country will be self-sufficient in a few years’ time and ready to export gas thereafter, as for the first time, raising gas production to at least the level of domestic demand is a priority of “all the credible candidates” for the March presidential elections. Whoever wins, the new era of transparency and regulatory stability will be here to stay, other speakers said.

There were some sceptics in the room. The Anglo-Dutch major Shell, for example, has an outstanding dispute with Kiev, in which it accuses Ukraine of pernicious behaviour, but that is in a different sector: petrol stations. Nevertheless it says it has still been unable to reach a settlement through the courts, and for the international oil companies with plenty of other places to invest, the attraction of investing in Ukraine is further diminished by such experiences.

This legal quagmire has also been the experience of independent producer JKX, for some years now awaiting the payment of interest relating to a rental fee dispute which JKX won in the Swedish court of arbitration but has yet to collect – rather like the award made against Gazprom in favour of Naftogaz Ukrainy, but a fraction of the size. Nevertheless, reporting rising gas output in the year to date compared with Q4 2018, JKX is seeking more gas reserves as its resources are 70% depleted.

The onus though will be on Ukraine to prove that it can forgo short-term budgetary dilemmas in favour of long-term revenue flows, if it wants to attract investors. This was the angle of other presentations. The head of the national investment council Yulia Kovaliv said that Ukraine had become the top country in improving its business climate in just a few years and seen 3.4% growth in GDP. In 2015 inflation was running at 40%; now it is 9.8% and the central bank expects it to be 7% this year or next.

When it came to trading, she said there were 30 companies in the gas market and they were thriving commercially and had made no claims against the state. “We have delivered on that key performance indicator,” she said. These include companies like German Uniper and RWE, French Engie and Swiss Axpo.

In neighbouring EU member Poland, by contrast, traders have closed down and left; Hungary and Romania have also proved to be unreliable supporters of the free market.

Ukrainian MP and deputy head of the parliament’s fuel and energy committee Olga Bielkova said that parliament had fulfilled all its upstream obligations with respect to land use and transparency. She said the fiscal regime was as attractive as any in the region – but also she said it was the best Ukraine can afford given the country’s difficult position – and now Ukrainian law mirrored European Union law, she said.

Apart from the state supplier Naftogaz Ukrainy, which uniquely has to deal with the public service obligations that force it to sell some gas to domestic users at a loss, every company is free to sell gas at the market price. And more producers are needed, Bielkova said: “I want to see more companies upstream. Seven is too few, they can manipulate the situation. Competition will lock in change and prevent a reversal to past practices.”

Gas production has the twin benefit of saving Kiev money on exports and on capturing more value from the producers’ expenditure on local goods and services. Consultancy Baringa estimates this could have a positive ‘economic impact’ of about $1.8bn/yr based on the amount of gas imported in 2017.

“The good news is that all the top, serious [a jibe here at the populist candidate Volodymyr Zelenskiy, a stand-up comedian who is leading the polls] – candidates are aligned with the priority of gas production,” Bielkova said. “Yes, there can be interruptions to the political cycle but nothing will change in that regard after the elections. I believe the president [Petro Poroshenko] will win a second term but whoever wins, all agree that we need to get more gas.”

On the other hand there is strong opposition to Poroshenko, not least in the shape of Ihor Kolomoisky, an oligarch believed to be funding another presidential candidate and also a co-owner of JKX for the past couple of years. Unlike some other billionaires, he has chosen conflict rather than co-operation with Poroshenko.

Bielkova said that the acreage had to be of interest as the parliament is fully aware of the priority of gas production. One change that could happen with the new parliament in November would be the strengthening of the state geology service, which could be rebuild on the lines of the UK, Canadian or Mexican regulators that work for the benefit of consumers. Another could be profits-based taxation. But she said the present parliament had been “a good friend” to investors, even if expectations may have been higher.

Transparency and the battle against corruption generally was the theme of deputy energy minister Natalya Boiko’s presentation. “It is a grey zone,” she said, “but one solution had been to join the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.” She said Ukraine was ready to publish a report on each of its upstream projects. Her department was working on the production-sharing agreements, now available for interested parties to look into. She recommended aligning Ukraine’s upstream access procedures with “the global standards.”

On the Gazprom transit agreement, she said that the Russian exporter wanted to merely extend the terms and conditions agreed in the past into the future; but that did not work, given Ukraine’s capacity regime was now aligned with the network codes of the European Union. International practices based on transparency and stability were needed, she said.

Bielkova conceded that the gas transmission system was a ‘holy cow’ for Ukraine and whoever is president will need parliamentary support to realise her goal of a fully independent transmission system operator, either with a management contract or an equity position. That would take the heat out of the discussions but it seems a distant prospect.

Prokhorenko makes way for new blood

One of the presenters at the event was Oleg Prokhorenko, the CEO of Ukraine's largest gas producer Ukrgazvydobuvannya and subsidiary of state-owned Naftogaz Ukrainy. He announced his departure less than a fortnight later, with effect from March 15. This was to do with corporate restructuring, his former employer Naftogaz Ukrainy said, thanking Prokhorenko for his success in ensuring production growth and introducing new ideas and technology, such as hydraulic fracturing, at a financially constrained time. He had held the post for three years.

He said the company's reserves replacement ratio was greater than 100% and that with the introduction of hydraulic fracturing two and a half years ago, gas output had grown faster than ever (see table). He had done deals with oilfield services company Schlumberger; and introduced an online tendering platform Prozorro to secure competitively priced goods and services. His sudden departure after this sort of record might not reassure outsiders.

Andrei Favorov, head of the integrated gas business who had been recruited from D-Tek, the company owned by Rinat Akhmetov – one of Ukraine’s richest businessmen – will take over the position until the board finds a permanent replacement, the company said February 8.

Naftogaz at the moment is an integrated company with pipelines, gas production, import and supply businesses.

Producers happy with the terms

An observer with some years of upstream experience of the country told NGW that previously the PSAs were negotiated behind closed doors: that is no longer the case. Another producer told NGW that the regime was better than ever for PSAs but finding investors was not easy, owing to the sums of money involved over the 50-year period of the PSA. The technical work and drilling commitments for the first five years were quite onerous, he said, and initial investments can be close to $1bn.

But investors under PSAs can recover 70% of their costs as ‘compensation’ before considering their share of the profit from the remaining 30%; imported equipment such as what is required for unconventional gas production is free from duty; and there is no tax on repatriated profits. The terms are also guaranteed fixed for the duration. They only change, he said, if the fiscal conditions in the rest of the country were to become more favourable. The state cannot change things for the worse without fully compensating the investor for the costs of those changes.

“The PSAs are very simple,” he said. “And if there is a dispute, it is to be resolved not in Ukraine but in international arbitration.”

He also said Ukraine had a large resource of intellectual capital, with no shortage of geophysicists and specialist engineers. But investors were naturally cautious before parting with the hundreds of millions of dollars such projects require, he said, and so negotiating with them takes time.

Discouraging history

Ukraine’s investment climate might have improved but the country itself is still a risky place to do business. Shell has pulled out of its Yuzivska acreage in the east, declaring force majeure after the Malaysian airliner was shot down. In the west, Chevron quit the Olesskoe shale gas project for which it had done the preparatory work. So far nobody has replaced Chevron while Shell’s stake is now owned by a Czech energy giant EPH, owner of the Slovak Eustream pipeline system. This leaves a question-mark over the likelihood of significant gas output growth.

Thanks to Russian armed intervention, the eastern republics of Donetsk and Luhansk are now in a state of frozen conflict, a tried and tested Kremlin tactic that clogs the wheels of the host government. The conflict has also brought out some violently nationalist elements elsewhere in the country, creating further difficulties for civil society. And since the Russian seizure of Crimea, the country has also lost about 1.5bn m³/yr offshore production.

Long-term Ukraine-watcher Simon Pirani told NGW: "The international oil companies have plenty of other opportunities for investment and those with long memories will think of Yulia Tymoshenko, a leading candidate for the presidency, and the way she illegally cancelled Vanco's offshore PSA a decade ago. And while the EU and the IMF have pumped money into the country to attract more investment, the results have been very limited.”

In an ideal world, Ukraine would have enough gas for its own needs and still be able to compete for market share in Europe against Russia. As it is, it imports about 35% of its demand through interconnectors with the European Union and so indirectly it is contributing a little to Gazprom’s record sales figures for the past few years.

Ideas for improvement

The European Bank for Reconstruction & Development commissioned consultancy Baringa to survey the Ukrainian upstream and see where it could be improved. It presented its recommendations to Ukraine’s parliament in late November – and a number of other entities since -- and included:

- Beef up the political support for the production-sharing agreement process from the government side as it was not clear that there was committed and concerted resource to support the process.

- Make unexplored or non-producing licences available to the market with safeguards in the form of “proper regulations and controls” and make it easier to trade or farm into licences.

- Base the role and functions of the state geological survey on principles of transparency and accountability.

- Allow state producer Ukrgazvydobuvannya (UGV) to partner with international gas companies to jointly develop resources. This could greatly increase its productivity. Service contracts may provide only limited returns and will not attract the international players.

- Adopt the Mexican ‘Round Zero’ concept where state-owned Pemex lost its statutory monopoly. That would allow UGV to hold the resource/ licences while holding a competitive process to bring in investors.

- Align upstream accounting to standard practices to ease some of the administrative challenges facing international players operating in Ukraine.