Keeping warm with Russian gas [NGW Magazine]

It is customary for Russian businessmen, in conversations about oil and gas, to claim that they are only pursuing business interests; they argue that it is the US that politicises the issue, using gas and oil to pursue broader geopolitical interests. Present-day Russia is not the USSR which, in most cases, neglected economic interests for geopolitical gain – an approach now pursued by China in its elastic Belt and Road initiative.

But neither is the present-day Russian elite the same as the Boris Yeltsin-era elite, for whom cash ruled supreme and no other form of payment was acceptable. Today, Russian policy is a combination of geopolitics and business, which has emerged as the result of a peculiar “symbiosis” of business tycoons – many of them having emerged during the Vladimir Putin era or inherited their property from the Yeltsin-era “privatisers” – and the assertive, idiosyncratic neo-Soviet/nationalist overtone of his successor.

In this new environment, gas is often used as leverage as a means to retain allies and punish enemies. The role that gas plays in this can be seen clearly in Russia’s dealings with Ukraine and Belarus. In the case of Ukraine, Nord Stream 1 has already deprived Kiev of considerable revenue and so increases the risk of political instability. Nord Stream 2 is on the way.

In the case of Belarus, comparatively cheap gas and oil keep Minsk inside Moscow’s orbit. This approach also persists in the case of Armenia and Moldova.

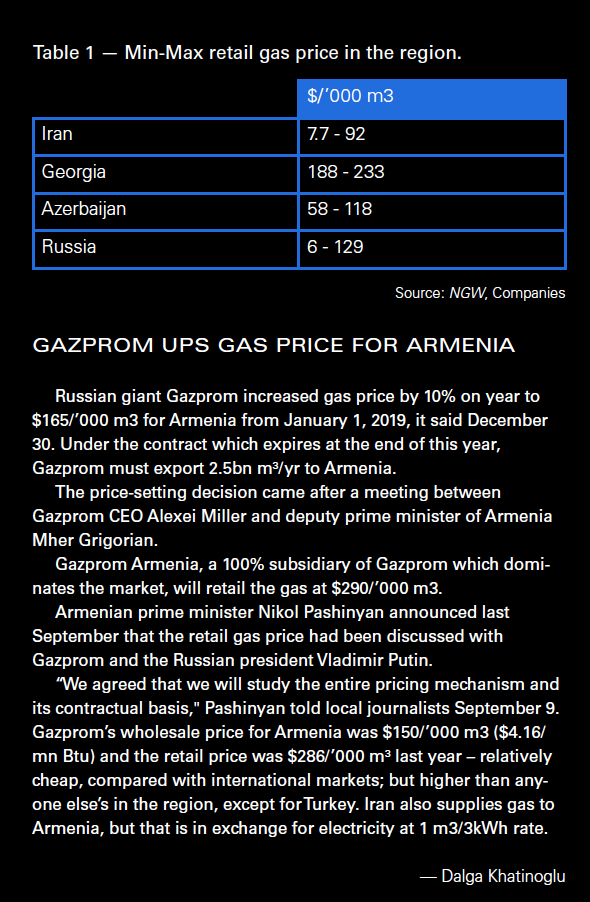

Punishing Armenia

Armenia, historically pro-Russian, has been a part of Russia’s security system, and Gazprom dominates Armenia’s gas market completely. After the May 2018 revolution, the new government tried to extract lower prices from Moscow and threatened to nationalise the Armenian transmission system which Gazprom controls, and through Gazprom, the Kremlin.

Yerevan also flirted with Tehran – Armenia has historically had a good relationship with Iran – and implied that it could get cheaper gas from Iran. But the new Armenian government’s foreign policy was hardly consistent. The relationship with Iran did not last long: the Armenian government decided to turn to the West and proclaimed that it would close the country’s border with Iran.

At that point, Russia had the upper hand: the Kremlin pretended that it already sold gas to the Armenia for quite a low price, and it was in fact Armenian entities inside the country that were charging end-users excessive prices. The Kremlin, in this case, called Armenia’s bluff, ignoring the inconvenient fact that Gazprom controlled the gas distribution system inside Armenia. It worked: the new government did not dare to renationalise it, despite its threat to do so.

The continuing high prices for Armenian customers appear as a means of punishing the Armenian government for challenging Moscow.

The flirtation with Moldova

The story looks different, or at least potentially different with Moldova, whose emergence as an independent state was far from trouble-free. This was mainly a consequence of its ethnic and linguistic composition. Moldova became a part of the Russian empire and later the USSR in parcels, so to speak. Part of the territory was acquired after the Turkish-Russian War, in the beginning of the 19th century. Other parts were acquired by the USSR in 1940, after Stalin struck an agreement with Hitler through the Molotov-Ribbentropp Pact of August 1939. The major goal for Hitler was to secure the Eastern flank in order to strike the West. For Stalin it was also an opportunity for a major land grab and Bessarabia was one of the new acquisitions. The territory belonged to Romania, at that time a German ally. Berlin wanted to keep Moscow on side however and so it did not oppose its annexation. While incorporated into the USSR as a constituent republic, Moldova has undergone the same linguistic and demographic changes as many other republics: the influx of a Russian-speaking population and the increasing domination of the Russian language in public discourse.

While the influence of the Russian language had been felt all over the country, the territorial division between different parts of Moldova has also become clear: the eastern region of Transnistria became predominantly Russian-speaking, and from this perspective, different from the rest of Moldova. The end of the USSR led to the split of Moldova into two parts, with Transnistria seeking political independence from the rest of Moldova. A short but bitter civil war followed which was stopped by Russian peacekeepers; but tensions between the two parts of Moldova remained high. While Transnistria gravitated to Russia, the rest of the republic gravitated to Romania, where lay their cultural roots.

Some Moldovans believed that they were actually Romanian and that their separation from Romania was only nominal. Logically they wanted to unify Moldova with Romania, or at least co-operate with it closely.

Moldova’s energy policy was also deeply connected with the pro-Romanian trend. It was assumed that Romania could produce enough gas to supply not just itself but also Moldova. For a while, there were plans to receive Turkmen gas. According to this plan, gas would be liquefied, transferred to Georgia, and from there to Romania. This idea gained strength from Russia’s conflict with Ukraine and the threat of disruption of the gas supply from the East. There had been continuous demand, for example, to withdraw Russian forces from Transnistria and move closer to Nato. In other cases, people in the capital Kishenev demanded that Russia should pay for keeping troops on Moldovan territory.

Logically, Moscow responded by implying that Moldova might begin to experience problems with Russian gas supply, especially after 2019, when Nord Stream 2 would reduce the importance of Ukraine as the avenue for Russian gas delivery to Europe. Lately however the Kishenev-Moscow relationship has improved. As in the case of nearby Ukraine, the Moldovan population is divided in its approach to Russia. The division here is not just between Transnistria and the rest of Moldova, but can be also seen inside Moldovan society, and has several causes.

One of the most important is the disappointment in the post-Soviet capitalist transformation and the belief that the EU could ensure Moldova’s prosperity. Russia remained an important economic partner, home to many immigrant workers from Moldova. Russia was also a buyer of Moldovan fruit, vegetables and wine, as well as its biggest gas supplier.

In search of compromise

Moldova’s president Igor Dodon tried to compromise. On one hand, he wanted to maintain the good relationship with the EU. On the other hand, he wanted to maintain the same good relationship with Russia.

But this showed a failure to learn from the mistakes of others. Viktor Yanukovich, the former president of Ukraine, had entertained the same flawed plan. On one hand, he wanted to keep the huge loans, actually grants, from Moscow, and the reduction, at least temporarily, of gas prices. On the other hand, he also wanted to integrate Ukraine into the EU and receive tangible economic benefits from this association too. But Moscow demanded full loyalty. The same was the case with Brussels. Yanukovich finally chose Moscow over Brussels, triggering a political crisis that led to his downfall, civil war and Russia’s annexation of Crimea. It also led de facto, if not de jure, to open-ended conflict between Ukraine and Russia. What was the outcome of the conflict for Moscow? Western critics of Moscow’s policy – and they clearly dominated the media space – assured the readers that it was the Kremlin that had instigated the conflict. Moreover, Putin’s imperialists regarded the Ukrainian conflict as the launch-pad for wider intervention on various excuses in the Bush-era ‘neo-con’ style.

The reality was much more complicated. It is true that the Kremlin benefited from the conflict by annexing Crimea and saving the Black Sea fleet. Indeed, the pro-Western government would most certainly have evicted Russia from Crimea and Moscow would have lost its Black Sea fleet for good.

Putin, like other global leaders, sensed that the US was far from being as strong as it was in the beginning of the post-Cold War era, and he took that into account when calculating the risks of taking Crimea.

At the same time, the prolonged conflict with Ukraine brought a clear problem for Putin and the Russian elite, whose interests he represents. The conflict in Ukraine has led to serious conflicts, not just with the US, but with the West. The tension complicated the Kremlin’s plans to build NS 2, the aim of which was to bypass Ukraine. The conflict has also led to anti-Russian sanctions and other problems. The Kremlin clearly wanted to solve the problems with Ukraine on mutually acceptable terms and it does not want to repeat the entire story in the future.

This has informed the Kremlin’s approach to Moldova: it understands that the Moldovan elite and society are split but trying to push the entire country in Russia’s direction would not achieve the Kremlin’s goals. It could even have the opposite effect. Consequently, Putin changed tactics, and offered Dodon a compromise. Moldova would not be a full-fledged member of the Moscow sponsored Eurasian Union, but would be just an ‘observer’. At the same time, Kishinev could maintain its relationship with the EU. Dodon is different from Moldova’s pro-Western parliament and actively promotes a pro-Russia policy. In July 2018, he commented that Russia was the major market for the republic’s agricultural goods. The breakthrough was the meeting between Dodon and Putin in Moscow, leading to lower tariffs on Moldovan agricultural produce. The Kishenev-Moscow detente has potential implications for gas deals.

Moscow-Kishenev relations and gas

The supply of Russian gas to Moldova and its price depend on the convoluted relationship between Kishenev and Moscow, and the contradictory nature of this relationship has continued almost up to the present. On one hand, there seems to be plenty of evidence that Kishenev wants to end its relationship with Gazprom, which it sees as an unreliable partner. Dodon said that Russia’s continuing conflict with Ukraine could lead to more serious problems for Russia’s gas delivery to Moldova and that a solution to this problem must be found.

At the same time, Gazprom management believes that Kishenev should pay for the gas sent to Transnistria. That was the point at which gas imports from Romania seemed attractive, at least to some Moldovan politicians. Some members of the Moldovan elite, notably those who see Moldova as part of the EU in general and Romania in particular, believe that Moldova could avoid dependence on Russian gas. But others have different views; at least their statements have become contradictory. Such is the case with Dodon. He noted, in the context of this narrative, that Putin implicitly promised Moldova a reduction in gas prices of 30%, together with other benefits; and that Moldova can expect a lot of cheap Russian gas. But he has also talked about the need to diversify.

The possible concession on gas prices creates an incentive for Moldova to move closer to Russia. Of course, one could wonder about the practical implications of Moscow’s assurances, but the cases of Armenia and Moldova demonstrate that Moscow actively uses gas when planning its broader geopolitical strategy.