Japan slow to tackle coal [NGW Magazine]

Japanese utility and major LNG buyer Jera announced in October that it will shut all of its inefficient coal-fired power plant by 2030, in line with government policy, and the company aims to be carbon neutral by 2050.

This suggests the country’s electricity utilities are finally getting to grips with a long-standing dependence on the high-carbon fuel.

Jera, a joint venture equally owned by Tokyo Electric Power Co Holdings and Chubu Electric Power, is the country’s largest power generator.

However, what constitutes an ‘inefficient’ coal plant remains an open question. The definition is being decided by the government. Jera said provisionally that ‘inefficient’ might mean any coal plant using supercritical technology or less.

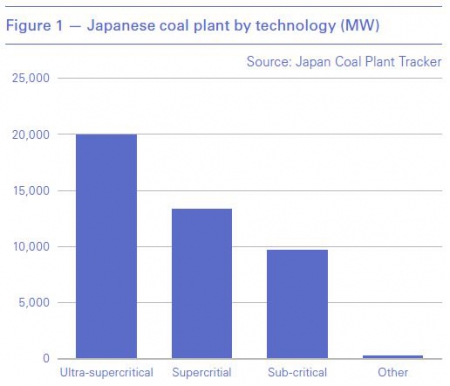

This definition would not be a great burden on the company. According to the Japan Coal Plant Tracker, the country has 43.4 GW of coal-fired plant in operation (Figure 1), of which Jera operates 7.3 GW, but only 1.4 GW of this plant is below Jera’s threshhold.

For the country as a whole, however, about 23 GW of capacity is ‘supercritical or less’, which would mean the closure of more than half of Japan’s coal-fired capacity, if all of the country’s utilities followed Jera’s lead.

However, even then Japan would retain substantial coal-fired generation capacity – around 20 GW. Ultra-supercritical coal plants have efficiencies of about 43%, and therefore emit less carbon dioxide per unit of power generated. But they still emit the same amount of carbon dioxide per ton of coal burnt, roughly twice that of combined-cycle gas turbines.

Moreover, Japan, never having had big gas fields, has not got the geology for carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) that the countries leading the way in this technology have. Retrofitting plants for CCS is not an option unless the carbon dioxide could be shipped to suitable storage sites abroad or alternative storage sites are found domestically.

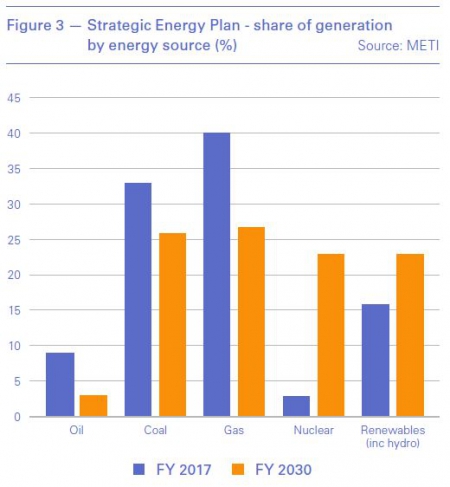

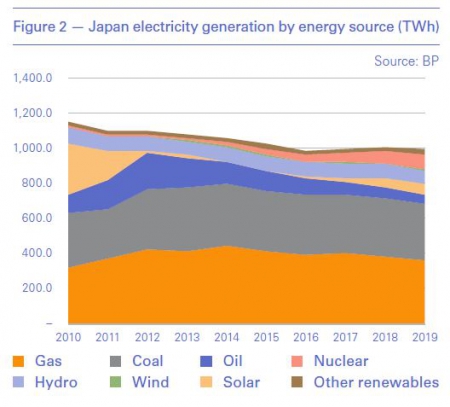

Coal is the second largest source of generation in Japan (Figure 2), supplying 32.6% of the country’s electricity in 2019, while natural gas, imported as LNG, accounted for 36.5%. The government aims to reduce coal’s share of generation to 26% by financial year 2030 from 33% last year and gas’s share from 36.5% to 27%, according to its strategic energy plan (SEP).

Decarbonisation efforts

Under the SEP, Japan’s power sector decarbonisation efforts (Figure 3) depend on much more nuclear plants returning to service than has been the case. Nuclear’s share of electricity generation should rise from 6.6% last year to 22-20% in 2030, while renewable energy capacity rises from 16% in 2017 to 22-24% in 2030.

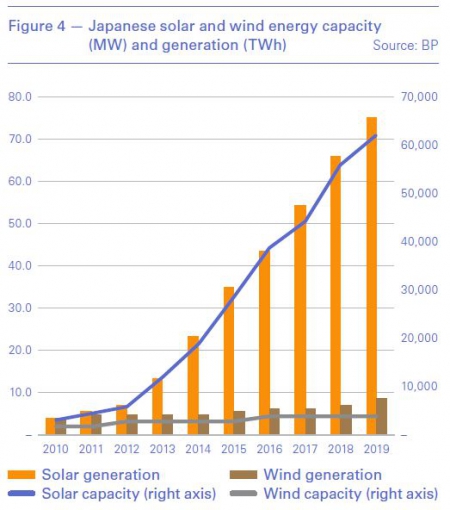

However, it looks highly likely that renewable energy sources will exceed their planned share in the generation mix. In 2019, renewables accounted for 19.6% of electricity generation (Figure 4). Solar photovoltaics (PV) generated 7.6%, already exceeding by 0.6 percentage points the planned target for 2030 of 7.0%.

Solar PV costs in Japan are substantially higher than the global average but are nonetheless on a downward trend. The country’s Renewable Energy Institute (REI), in its October 2019 report Solar Power Generation Costs in Japan, estimated that the average cost of Japanese solar PV in 2018 was $160/MWh, compared with a global weighted average cost of $57/MWh in the first-half of 2019. For the most efficient installations, Japanese solar PV generation costs were approaching electricity exchange prices.

The higher costs were attributed not to more expensive hardware, but mainly to higher construction costs and bigger margins. However, this has not deterred installations. Japanese solar capacity leapt by 11.2 GW in 2018 and 6.3 GW in 2019 to a total of almost 62 GW, putting it on a par with the US.

However, costs could well turn out lower. This year has seen record prices offered into utility-scale tenders for solar PV internationally. In July, a tender was awarded at $13.5/MWh in the United Arab Emirates, a level replicated in August with a bid into an auction in Portugal of $13.2/MWh.

Even if Japan stays behind the curve on a global basis, the downward drift of solar PV costs mean it will be one of the most competitive forms of generation over the next decade.

Wind power

Japan has been relatively slow to embrace wind power with only 3.8 GW capacity installed at the end of 2019, of which just 65.6 MW was offshore.

However, the potential offshore wind resource is huge, even assuming only fixed-base installations rather than floating wind farms. Much of Japan’s nearly 30,000 km of coast has sea beds which fall steeply away from shore.

In its Offshore Wind Outlook 2019, the International Energy Agency estimated that Japan could generate nine times its current electricity demand from offshore wind based on its technical potential. Technical potential excludes sea areas which are environmentally protected or used for other purposes.

Regulatory barriers to offshore wind development are or have been removed. In particular, a law was introduced in April 2019 which allows offshore wind farms to operate for 30 years. It designated eleven development sites and laid out for the first time a legal framework for the use of Japan’s ‘general waters’.

Ministry of energy, technology and industry (Meti) data shows 13 GW of offshore wind projects are being considered by developers and the Japan Wind Power Association said in January that 1.398 GW of offshore wind capacity has embarked on the environmental assessment process, in addition to 1.518 GW of onshore wind. In June, the government started its first auction for an offshore wind farm in Japan’s general waters in the Goto sea area for a floating wind farm.

In 2019, wind accounted for 0.9% of the country’s electricity generation and the target for 2030 is just 1.7%. This target was formulated before the current upsurge in interest in offshore wind, which followed large reductions in cost in north European projects and generally has higher capacity factors than onshore wind. As with solar, there is a high probability that Japanese wind power will exceed its 2030 target by some margin.

The nuclear question

The future of nuclear power in Japan remains a major uncertainty governing gas demand. Just as gas market deregulation forced more price risk on to generators, thereby encouraging more interest in zero fuel cost renewables, electricity market deregulation means few if any companies are likely to take on the risk of nuclear newbuild.

The country’s existing reactors, where the original costs are sunk, should remain competitive, but they have faced costs and delays following the 2011 Fukushima disaster in order to meet stringent new safety regulations and building requirements. So far, 24 reactors have been permanently shut down.

Nuclear restarts have been slow. Meeting the government’s 2030 target of 20-22% generation from nuclear would require all of the country’s 30 still-operable reactors to return to service. To date, nine reactors have returned and 18 are in the restart approval process. In March, two operating reactors, Sendai I and II, were shut down for missing a five-year deadline for building facilities, but they are expected to return to service by the end of the year.

Gas outlook

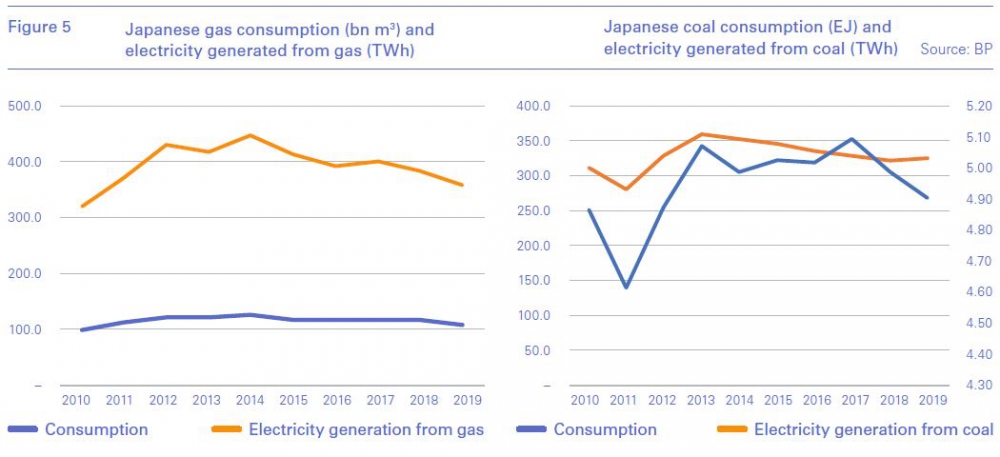

Both gas and coal consumption (Figure 5) jumped following the Fukushima disaster as Japan made up for the huge loss of generating capacity by all means necessary. But since 2013/14, there has been a gradual decline in consumption for both fuels. This reflects structural factors; flat electricity demand; the gradual return of nuclear generation; and rising renewable energy capacity.

The mid-to-long term outlook for energy demand remains on a downward trend, largely as a result of Japan’s declining population and energy efficiency improvements.

Covid-19 will mean a further hit to already weak economic growth. Before the pandemic struck, the Institute of Energy Economics Japan (IEEJ) was predicting GDP growth of 0.6% in 2020/21. In April-June, GDP fell 7.8% from the previous quarter.

LNG imports from January to September were 33.4mn metric tons, down 6.5% year on year. For the 12 months to March 31, Japan imported 76.5mn mt, down 5% year on year. If the SEP is realised in terms of reduced gas-fired generation, LNG imports would fall to 62-64mn mt/yr by 2030.

New leadership – new policies?

A change of guard at the top as prime minister Shinzo Abe steps down for health reasons and Yoshihide Suga takes over is unlikely to see any immediate major changes in energy or climate strategy. Faced with an economic slump, Suga’s policy options are constrained by the country’s high level of debt, which is largely the result of economic stimulus packages in the early era of ‘Abenomics’ that had been designed to rescue the country from deflation.

More radical change could come though, if the septuagenarian Suga proves a caretaker prime minister until the next election in September 2021 and then makes way for new leadership.

An accelerated expansion of renewable energy seems highly probable as a result of falling costs and Japan’s long-standing desire to reduce its heavy dependence on imported fossil fuels. It is also likely that with growing renewable energy generation, more ambitious climate change policies will become more achievable.

Japan could reduce its greenhouse gas emissions faster if gas-fired generation were prioritised over coal, but Japan’s utilities, while increasingly open to renewable energy, also want to protect their existing generation assets. Any change in policy would face strong industrial lobbying. Japan’s ultra-super critical coal plants were built between 1994 and 2013, so even the oldest have more than a decade of commercial use left in them.

Another aspect of Japan’s recent changes to coal policy was to tighten restrictions on government support for coal technology exports. Japan has supported the construction of ultra-super critical coal plant by Japanese firms in countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia.

The new restrictions were welcomed by environmental groups, but they also pointed out significant exemptions which bring into question just how restrictive the new policy might be. Environmental groups hope that weaker prospects for coal technology exports will gradually shift the focus of Japan’s utilities away from coal domestically.

Fossil fuel squeeze

The degree and speed of nuclear’s return will play a key role. If it performs according to plan, the combination of rising renewables and nuclear generation would certainly squeeze fossil fuels, setting LNG demand on the downward path envisaged in the SEP. However, the slow return of reactors so far suggests the country’s nuclear ambitions will probably fall short.

In this scenario, fossil fuel generation still drops as over-achievement in renewables is offset by under-achievement in the nuclear sector.

Hydrogen and even ammonia also now pose threats to natural gas in the power generation sector. In late September Japan took delivery of the world's first shipment of 40mn mt of blue ammonia, the result of a partnership between IEEJ and Saudi Aramco's petrochemicals arm Sabic.

Natural gas was used to produce hydrogen at a plant in the Saudi port of Jubail and then combined with nitrogen to create the ammonia. The carbon dioxide extracted from the gas was captured and used at a methanol plant in Jubail and an enhanced oil recovery (EOR) pilot plant in Uthmaniyah.

Aramco CTO Ahmad Al-Khowaiter said the operation showed the potential of Aramco's hydrocarbon reserves as a source of low-carbon hydrogen and ammonia. IEEJ CEO Toyoda Masakazu estimated that 10% of Japan's power could be generated using 30mn mt/yr of blue ammonia.

"We can start with co-firing blue ammonia in existing power stations, eventually transitioning to single firing with 100% blue ammonia," he said. "There are nations such as Japan which cannot necessarily utilise carbon capture and storage or EOR due to their geological conditions. The carbon neutral blue ammonia/hydrogen will help overcome this regional disadvantage."

Given the alternatives ranging up against gas, perhaps the most promising, or least bad scenario is that a new government adopts more ambitious climate change targets, takes on the coal interests and imposes either a coal phase out policy, emissions trading or an effective carbon tax.