Ireland’s ‘world-leading’ transition [NGW Magazine]

Policymakers and energy companies in Ireland have been playing catch-up with the nation’s obligations on climate and its commitments to the European Union (EU) under the third legislative package on energy. The various energy reforms that are being pursued are starting to bear fruit.

At the beginning of October a new wholesale electricity market arrangement for Ireland and Northern Ireland – known as the Integrated Single Electricity Market, or I-SEM – began operating. A single all-island electricity market had been operating since 2007, with an interconnector between north and south, but it did not conform with the EU’s common rules for electricity markets and cross-border transmission. I-SEM does.

Ireland has also been striving to meet its binding EU target for 16% of the country’s total energy consumption to come from renewable energy sources by 2020. This is proving to be a struggle because not enough progress has been made in renewables penetration into the transport and heat sectors.

Electrifying progress

Electrifying progress

The electricity sector is a different story. To meet the overall target of 16%, the sector was given a target for 40% of generation to come from renewables by 2020. Jonathan O’Sullivan, innovation manager at EirGrid, Ireland’s transmission system operator (TSO), is confident that the target will be met, with onshore wind by far the biggest contributor.

The technical and operational challenges that need to be overcome to meet this target are formidable – so much so that when it comes to integrating variable renewable generation into an isolated grid, Ireland is leading not just the European Union but the world.

To achieve an average of 40% of electricity being generated by renewables, the energy grids in Ireland and Northern Ireland will need to be able to handle 75% of variable renewable electricity at any one time – the system non-synchronous penetration operational limit, or SNSP.

To achieve this, a long-term programme, Delivering a Secure Sustainable Electricity System (DS3, for short), is under way. The power system can already handle a record-breaking SNSP of 65%, says O’Sullivan.

A growing role for gas

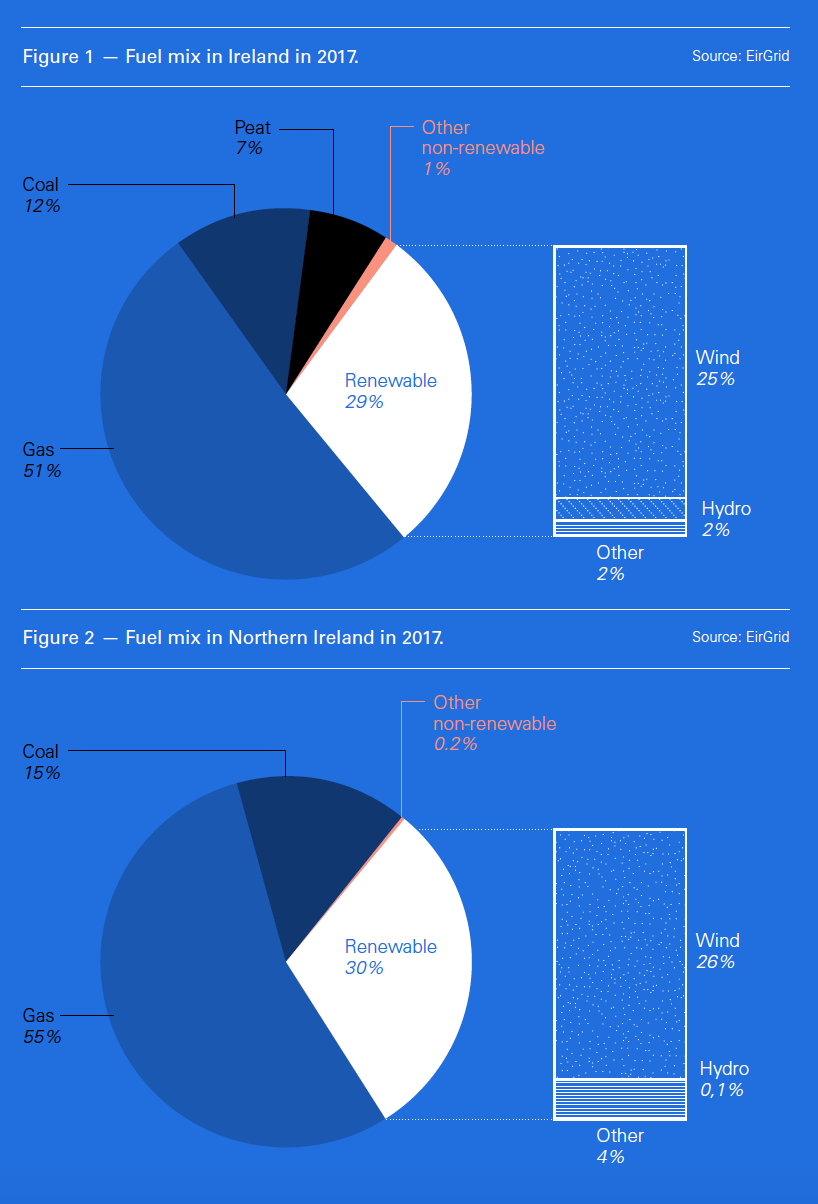

Both Ireland and Northern Ireland (part of the UK) are already heavily dependent on natural gas for electricity generation, as the charts below show. In both cases, gas accounted for just over half the electricity fuel mix in 2017.

Ireland still relies on coal and peat for a fifth of its power, while Northern Ireland relies on coal for 15%. However, the days of burning coal and peat are numbered, partly because of the rapid growth of renewables and partly because of climate policies.

The UK has a policy of phasing out coal from power generation by 2025 and the only coal-fired power station left in Northern Ireland, Kilroot at Carrickfergus, is nearing the end of its operational life.

As for Ireland, in March 2018 the then energy minister Denis Naughten announced the country was joining the Powering Past Coal Alliance and had committed to converting the 900-MW Moneypoint coal-fired power station to less-polluting fuel by 2025. Gas seems to be the favoured option. Subsidy support for peat, a more polluting fuel than coal, will end in 2019 and is unlikely to be renewed. Moreover, there is a deadline of 2030 to phase out peat altogether.

As coal and peat are pushed out of the system, natural gas is expected to play a growing role in backing up variable renewables.

“Not only does gas support Ireland’s vital but intermittent renewable generation,” says Ian O’Flynn, head of commercial at Gas Networks Ireland, the gas TSO; “it also ensures that the use of heavy-emitting generators, such as coal-powered Moneypoint and peat stations in the midlands, is kept as low as possible.”

He adds that during the summer of 2018 gas was at times supplying 90% of the nation’s power because there was so little wind.

A recent report from the energy ministry – the Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment (DCCAE) – says: “It will remain necessary for a certain level of gas-fired generation to continue to be available to ensure continuity of supply and the integrity of the electricity grid during the transition towards a low-carbon energy system.… A proportion of Ireland’s electricity needs will likely continue to be generated from gas over the medium to longer term.”

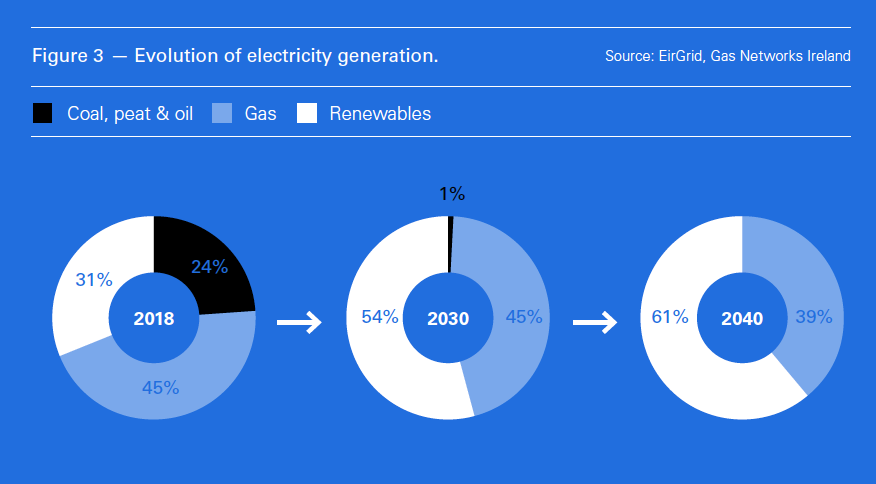

This is explored further in a Long-Term Resilience Study published by EirGrid and Gas Networks Ireland and commissioned by the DCCAE.

In a median scenario it forecasts that gas demand will grow 17% by 2030, while a high-demand scenario would see growth of 27%. This is despite wind capacity growing from the current level of 3.08 GW to over 7 GW by 2030. The share of gas in the median scenario remains the same because overall electricity demand also grows.

But keeping a large electricity network resilient is not just a matter of supplying sufficient energy. To keep voltage and frequency within the required narrow tolerances it is necessary to manage not just active power but also reactive power.

Despite the falling costs of battery storage, the level of storage capacity in most networks is limited, so generation has to match demand changes closely in real time. The unexpected outage of a large generator or interconnector can play havoc if a system does not have a high level of resilience. To keep a network resilient requires a variety of what TSOs call “ancillary services”.

Conventional power stations in which large metal generators are rotating synchronously provide a level of inertia that makes a network inherently more stable than one in which there is a high proportion of non-synchronous generation, such as wind and solar power. The objective of the DS3 programme is to keep an electricity network resilient as the proportion of variable non-synchronous generation grows.

Of all the energy reforms and projects under way in Ireland, it is the DS3 programme that stands out as a world-leading initiative that other nations can learn from.

The spectre of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit

As Britain careers towards Brexit – its intended exit from the European Union, with the March 2019 deadline now only a few months away – the prospect of a hard border on the island of Ireland has emerged as a potential threat, not just to peace and general trade but also to the Integrated Single Electricity Market (I-SEM).

There appear to be three possible outcomes: a negotiated withdrawal; a “no-deal” scenario, the hardest of hard Brexits; or no Brexit at all.

Both the UK and the EU have been at pains to ensure that any withdrawal agreement protects the I-SEM. The current draft specifies that: “The provisions of EU law governing wholesale electricity markets listed in Annex 7 to this protocol shall apply.… in respect of Northern Ireland.” Annex 7 goes on to list the relevant pieces of EU legislation.

If Brexit does not happen – a slim prospect as things stand – clearly there is nothing to worry about.

As for a no-deal Brexit, a technical notice regarding the trading of electricity published by the UK government in October makes for alarming reading.

“If there is no deal,” it says, “EU rules will cease to apply in Northern Ireland, leaving key elements of the single electricity market – trading with Great Britain and cross-border governance arrangements – without any legal basis. Given the benefits to consumers and the economy of the more efficient, shared market, it is strongly in the interests of all parties to agree to a means to avoid the split of the market.”

The government says it would work with the Irish government and the European Commission to come up with some kind of agreement that allowed the I-SEM to continue. But it concedes that “there is a risk that the Single Electricity Market will be unable to continue and the Northern Ireland market would become separated from that of Ireland”.

The impacts north and south of the border would be damaging to producers and consumers alike and would leave governments scrambling to mitigate the effects.