Investors force change [NGW Magazine]

During May the three super-majors – Shell, BP and ExxonMobil – had their annual general meetings (AGM). They all faced shareholder resolutions demanding actions to combat global climate change, but with different outcomes. Nevertheless the concessions made during the AGMs are the beginning of change in the oil and gas industry with potentially far reaching consequences in the longer term.

So far Shell and BP have been taking similar positions on climate change, by acknowledging the threat and the need for action, trying to become part of the solution, but nevertheless carrying on with their mainstream business of developing and exploiting oil and gas.

ExxonMobil has been more hesitant to follow suit, but it acknowledged the need for action more recently.

Shell

Shell CEO Ben van Beurden summed up the company’s strategy at its AGM when he said “our strategic ambitions are to deliver a world-class investment case, to thrive in the energy transition, and to maintain a strong societal licence to operate” – a position also taken by Shell’s chairman, Charles Holliday.

Van Beurden confirmed how Shell has been adapting to changing customer needs as the global energy transition progresses towards a lower-carbon future.

Shell has already set short-term targets to reduce the ‘net-carbon–footprint’ of the energy products it sells by around 20% by 2035 and by around half by 2050. It also set a target to limit methane emissions intensity below 0.2% by 2025.

But van Beurden also added: “We will do this in line with society because both energy demand and energy supply must evolve together. No business can survive unless it sells things that people need and buy.”

Shell is already investing in clean energy in the power sector. It is now getting involved at almost every stage of the sector, from generating electricity, to buying and selling it, and supplying it to customers. Shell believes that the changes in the power industry – more volatility and intermittent supply and demand – are playing to its strengths. It sees this as an opportunity to use the power of its brand and its global customer base to supply not only electricity, but also related services such as car charging, home-based battery storage and smart energy demand optimisation.

Van Beurden said that having a large customer base alongside clean power generation assets gives Shell the opportunity to trade, integrate and optimise. But it would still need to prove the investment case before scaling up.

Shell is also investing in ‘nature-based solutions’ (NBS). On 8 April, it announced a programme to invest at least $300mn in natural ecosystems.

He confirmed that these initiatives have been developed through extensive collaboration with institutional investors working on behalf of Climate Action 100+, an investor initiative launched in 2017 to ‘ensure the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take necessary action on climate change.’

In an industry first, under investor pressure, Shell agreed to link achievement of its carbon emission targets to executive pay, subject to a shareholder vote in 2020. This could be a massive step change. A similar resolution was approved by Total’s shareholders at the French company’s AGM in May, to include climate change targets in its chairman’s pay deals. BP and Chevron have also committed to link employee bonuses to climate-related targets.

In another concession to investors, Shell pledged to review its membership of industry lobbying groups which may take a stance on climate-related topics that undermines the goals of the Paris deal.

Responding to the evolving energy landscape, Shell is redirecting its business into three strategic themes, Core Upstream, Leading Transition and Emerging Power. Its aim is to reshape its portfolio and drive capital allocation for value growth. In particular, the Emerging Power theme will focus on creating business models to meet evolving customer demands as society transitions to much greater levels of electrification.

The company’s position was summed up by Shell’s UK vice president for upstream Steve Phimister, who said during Oil & Gas UK’s industry conference in May that the country needs to take decisive action on the issue of climate change, but not including abandoning oil and gas. This will not happen overnight and “in the meantime, producing oil and gas as well as low carbon energy we see as complementary, not contradictory.” Shell supports a fast energy transition and so does BP.

BP

BP had a more dramatic start to its AGM week. Climate protesters blockaded its London office the day before the AGM.

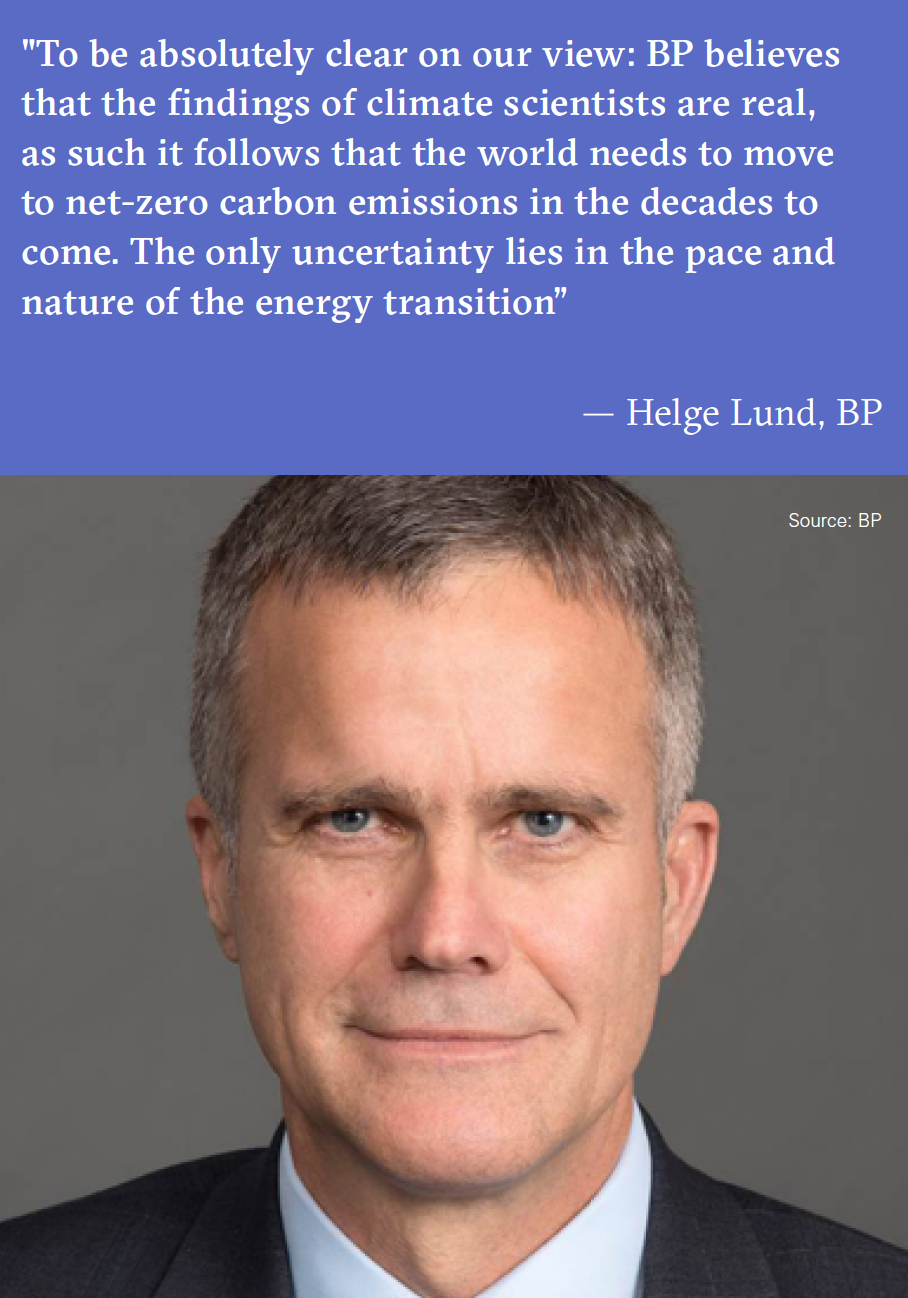

BP’s position on climate change is well articulated in an article in the Financial Times by its chairman, Helge Lund, entitled ‘Why BP supports a fast-shift to low carbon’.

BP has not set up targets like Shell, but it has accepted and adopted a resolution proposed by Climate Action 100+. This commits BP to greater transparency and greater disclosure in showing how its strategy is consistent with the goals of the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change.

Lund said: “We recognise that the world is on an unsustainable path. We believe our strategy is consistent with Paris. And we welcome steps, such as this resolution, that are supportive of a faster transition to a low carbon energy system.” He added: “To be absolutely clear on our view: BP believes that the findings of climate scientists are real, as such it follows that the world needs to move to net-zero carbon emissions in the decades to come. The only uncertainty lies in the pace and nature of the energy transition” – a bold statement.

But despite this, BP was unable to support, and defeated, a second resolution at is AGM to include emission targets in its future strategy. BP objected to this because it has no control over such emissions and “this does not allow for flexibility and would restrict its ability to transform in response to the uncertain path energy transition will take.”

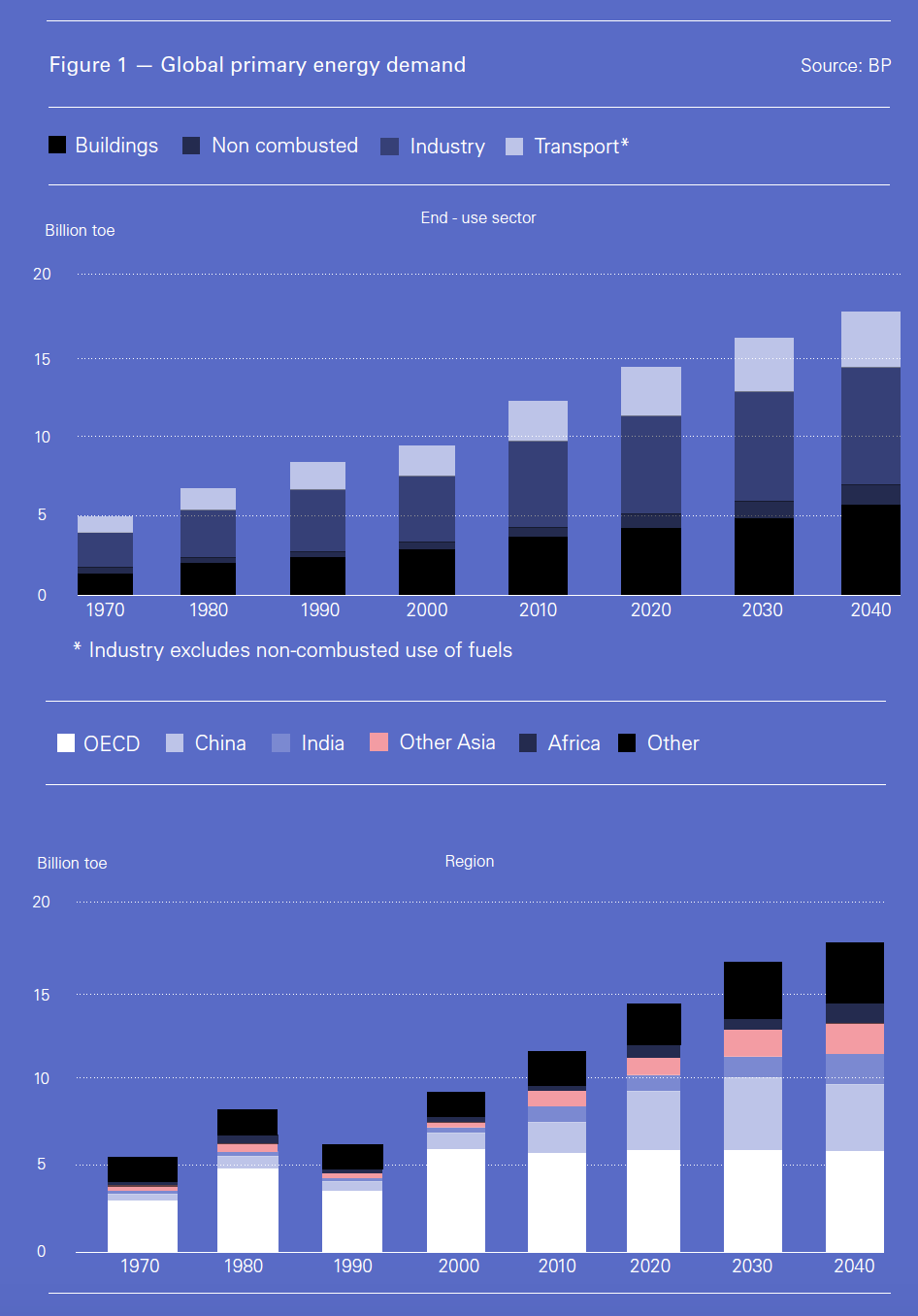

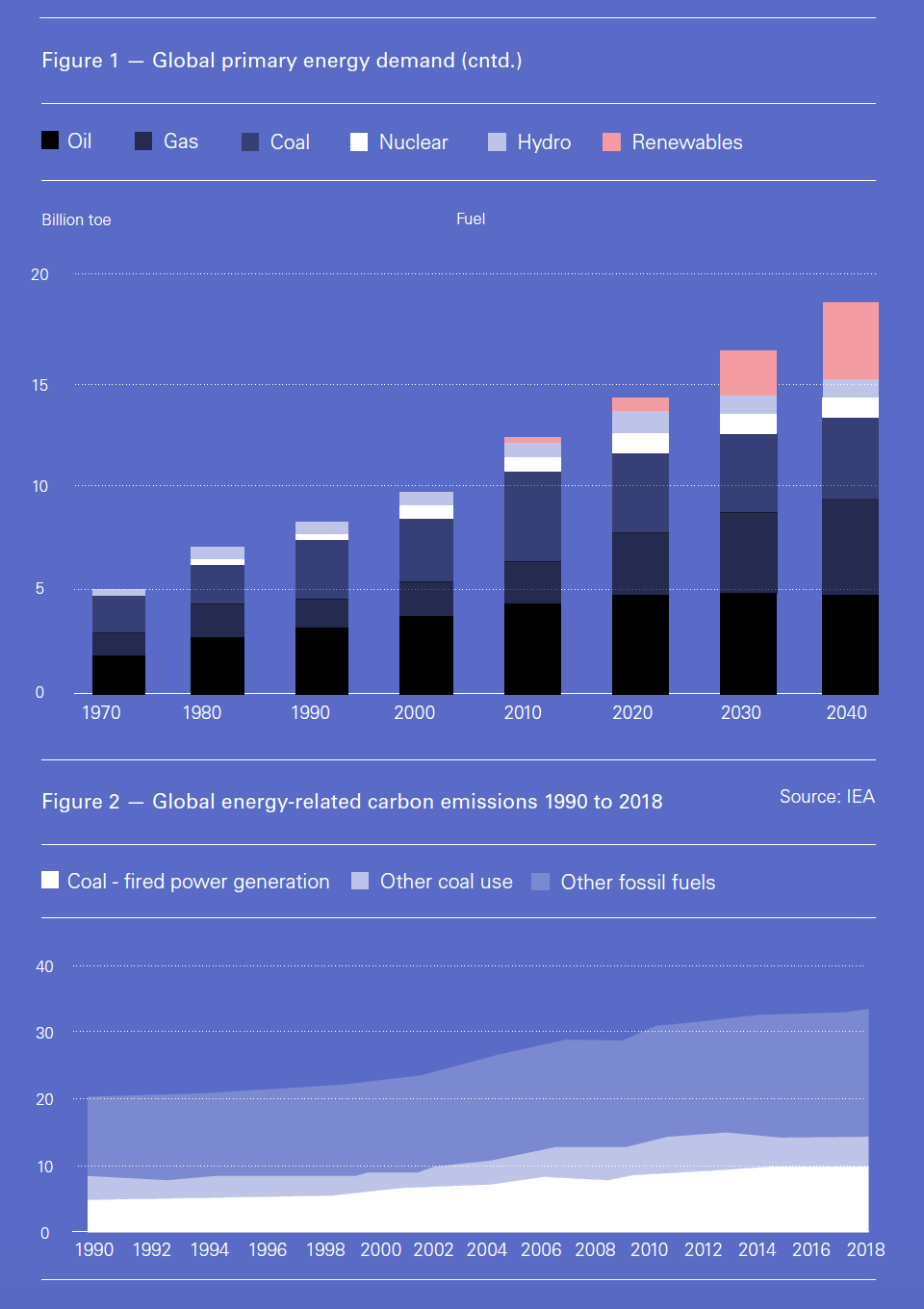

BP recognises that the longer carbon emissions continue to rise, the harder it becomes to achieve timely transition. But equally, it accepts in its BP Energy Outlook 2019 that the world will need more energy in the period to 2040 – the reference period considered in its Outlook (Figure 1). The majority of this increase in global primary energy demand comes from higher income per head in the developing world. Unless more, affordable energy becomes available this rising prosperity will be suppressed.

This is what led Spencer Dale, BP group chief economist, to say: “We are seeing growing competition between different energy sources, driven by abundant energy supplies, and continued improvements in energy efficiency. As the world learns to do more with less, demand for energy will be met by the most diverse fuels mix we have ever seen.”

This is the environment within which BP is battling to balance the two worlds: providing the additional energy the world needs while working to control emissions, that at present are still rising (Figure 2). But as the company says, it cannot go it alone in this direction. It burned its fingers 20 years ago, when it tried that with its ‘Beyond Petroleum’ initiative.

Lund committed BP to being part of the solution, which is to re-engineer the energy system to deliver the additional energy the world will need with much-reduced emissions. He concluded: “Apart from being the right thing to do, it is simply in our own best interests.”

ExxonMobil

Pressure on US oil and gas companies from investors over climate change has in general been less than in Europe. In fact, in April ExxonMobil, with support from the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), succeeded in blocking a vote on a proposal on setting emissions targets.

New York State’s pension fund, the Church of England and other investors had called for ExxonMobil to start setting targets for reducing emissions in line with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement, but the SEC ruled that the company could keep the proposal off the ballot at its annual shareholder meeting in May – which it did.

In addition, shareholders did not approve resolutions calling for the setting up of a special board committee on climate change and to report political contributions and lobbying.

A recurrent proposal at ExxonMobil AGMs to split the chief executive officer and board chairman roles, by appointing an independent chairman, was also defeated, but less narrowly than in the past: it received 41% of the votes.

Shareholders also rejected another climate-related resolution, which called for the company to publish a report “assessing the public health risks of expanding petrochemical operations and investments in areas increasingly prone to climate change-induced storms, flooding and sea level rise.”

In 2017 shareholders voted against the board and forced the company to improve its disclosure of information related to climate change. But so far they have not succeeded in forcing the company to set targets toward meeting the 2015 Paris climate agreement to limit global warming.

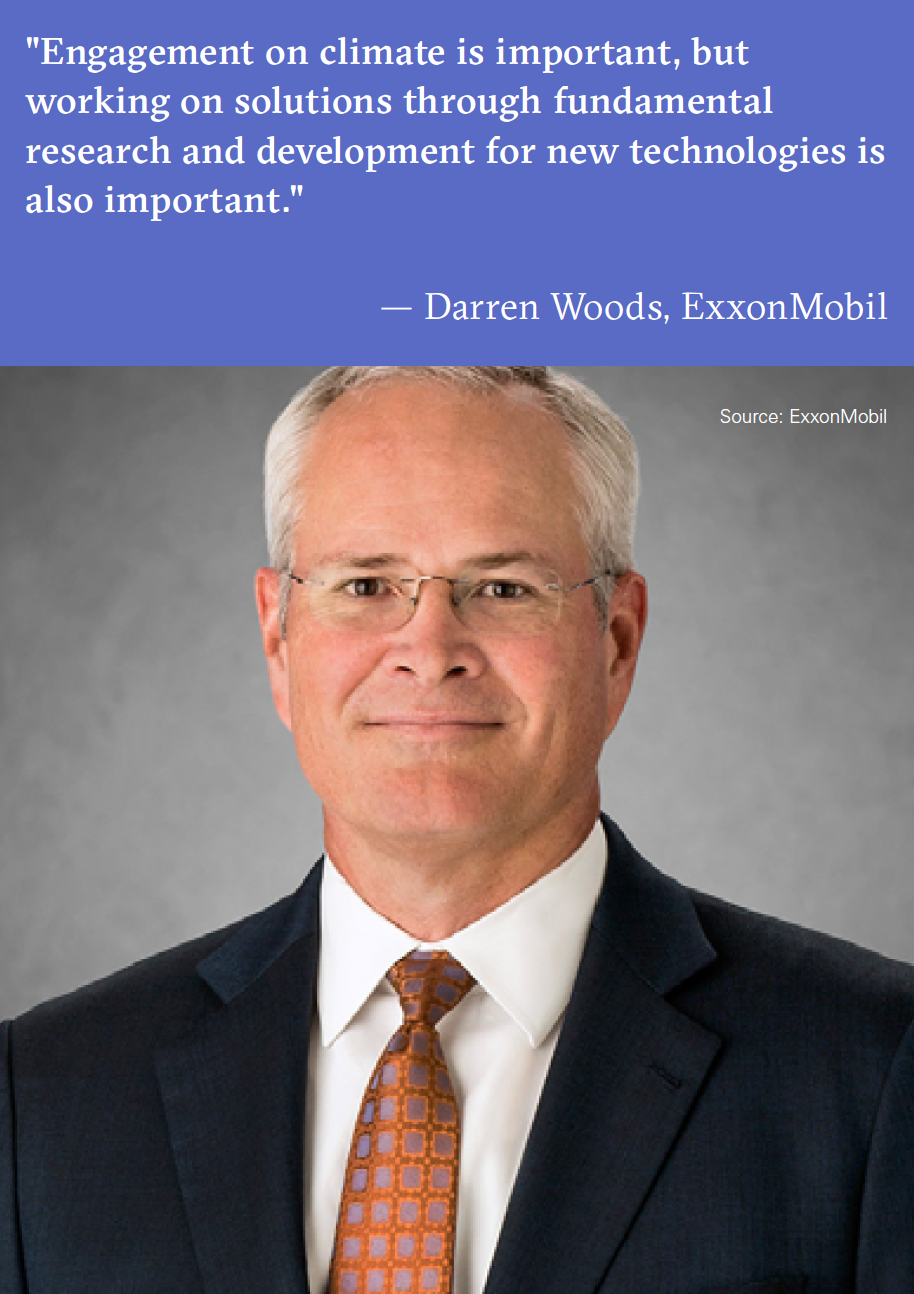

CEO Darren Woods said the company will continue to engage with shareholders, adding: “Engagement on climate is important, but working on solutions through fundamental research and development for new technologies is also important.”

But he has recently committed $100mn over ten years for ExxonMobil to partner with the US Department of Energy's national labs to research and bring lower-emission technologies to commercial scale.

In the meanwhile, demonstrating its commitment to its core business, ExxonMobil launched major expansion programmes to find and produce new reserves of oil and natural gas, as well as to expand the company's refining and chemical footprint. It is also targeting shale production of 1mn barrels/day at the Permian Basin as early as 2024.

Even though shareholders have been pressing the company to define a path toward meeting the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement, ExxonMobil has not yet committed to any targets.

Also in the US, at the company’s AGM in May, Chevron Corp's shareholders rejected three environmental resolutions: proposals to create the company's own board committee on climate change; to report on reducing carbon footprint; and to report on the human right to water.

However, in response to shareholders’ demands, the company published reports in 2017 and 2018 on its climate change risk management.

Increased litigation

In the US, and also in Europe but to a lesser extent, activists are prepared to use climate change litigation to force oil and gas companies, and government, to act. These are bringing up new legal questions in the context of climate change for the first time. Most may not succeed, but it only takes one successful case to set precedent. A well-known case was brought in 2018 by New York state against ExxonMobil claiming that the company defrauded shareholders by downplaying the expected risks of climate change to its business.

Local authorities in the US are also increasingly bringing up climate change liability lawsuits seeking damages for a variety of what they consider to be climate-related problems. But so far none have succeeded and many have been thrown out.

But energy companies, including Shell and BP, cannot ignore these. They are lobbying for a new carbon tax bill that would also include a liability waiver for fossil fuel products sold in the past. This would make most of these lawsuits vanish.

But energy companies, including Shell and BP, cannot ignore these. They are lobbying for a new carbon tax bill that would also include a liability waiver for fossil fuel products sold in the past. This would make most of these lawsuits vanish.

However, until that happens litigation will continue. The logic is that while the energy companies have to fight every case, the activists only have to win one.

Challenges

Following these AGMs, there was considerable criticism that the climate change commitments recently made by oil and gas companies do not go far enough. It of course remains to be seen how these unfold, but nevertheless they constitute important first steps in what promises to be a relentless battle with shareholders and activists to face and respond to the increasing challenges of climate change.

The greatest challenge is that the scale of the required changes in the world’s energy system, and the pace at which they are required to happen, are unprecedented. They would cause massive upheaval not only in the way energy is produced and consumed, but also in all aspects of society.

Oil and gas companies are being pushed to cut emissions from fossil fuel extraction and processing, switch to producing low-carbon fuels, such as gas over coal, improve efficiency in transmission and distribution, invest in new technologies such as carbon capture and storage and boost their presence in renewables.

In all of this, the fact that independent oil and gas companies control only a relatively small part of the oil and gas industry is often missed. Investors and activists have no impact on state-owned energy companies that produce almost 80% of the world’s oil and gas. Any gap left by the independents, or inability to compete, could be filled by state-owned companies. As consultancy E3G CEO Nick Mabey said “Investors would do more good if they pushed governments into creating policy that would bring certainty about how energy companies should operate.”

There are also practical questions to consider. How possible is it to achieve the massive changes required, while keeping the lights on, and how affordable would this be? This is more so in Asia, where more energy is consumed, than in Europe (Figure 1).

But even in the UK, the government has been warned that going for net-zero emissions by 2050 could cost the country more than £1trillion, render some industries economically uncompetitive and hurt public spending.

Van Beurden said at last year’s Oil & Money conference in London: “You can get to 1.5 °C, but not by just by pulling the same levers a little bit harder, because they are being pulled roughly as fast and as hard as we are currently imagining.” He added: “It’s not what some people sometimes think: we’ll just do a little bit more solar, a bit more wind and we’ll get there.”

The problem was highlighted in this year’s Statistical Review of World Energy just released by BP. CEO Bob Dudley said: “Decarbonising the power sector while also meeting the rapidly expanding demand for power, particularly in the developing world, is perhaps the single most important challenge facing the global energy system over the next 20 years. Renewable energy has a vital role to play in meeting that challenge. But it is unlikely to be able to do so on its own.”

Van Beurden stressed that the oil and gas companies understand what needs to be done, but at this stage how to get there is not clear. It also would not be commercially viable without major changes to government policies. He said that even though Shell is and will be investing more in renewables in future, its core business is, and very much will remain, in oil and gas. The energy sector also has an obligation to ensure enough energy supplies are available for the world.

BP’s views are similar. Dudley warned of the risks associated with meeting investor demands for change. He said that “forcing companies to predict an uncertain future using simple assumptions would almost certainly be wrong and, possibly, leave them open to legal action.” He also warned that insufficient spending on new oil and gas production could have far-reaching consequences for energy security across the world. The world still requires oil and gas during energy transition, meaning that there is a responsibility to carry on producing.

Energy firms are quite willing to work with governments to achieve energy transition. Dudley summed this up when he said at the Oil & Money conference: “We can do this even faster and more efficiently with clearer, smarter policy signals from governments.”

The International Energy Agency (IEA) also recommends that governments, not just the energy industry, must take the lead with policies to achieve climate targets to contain global warming. As experience shows, without a major shift in policies change will be slow.

But, shareholders also want to make sure the oil and gas companies they invest in can thrive and their assets do not become uneconomic. Worried about the impact on their wallets, there is pressure on oil and gas companies to manage potential asset value decline and prioritise shareholder returns.

The oil and gas companies have been responding to this by controlling spending and boosting dividends. Shell’s recent announcement that it is setting aside $125bn between 2021 to 2025 to boost distributions to investors is a good example of this.

Oil and gas companies also have to deal with public perception. The industry still needs to overcome mistrust and make the case that it has a genuine desire to work towards achieving climate targets.

However, it is clear from this year’s AGMs that a growing number of asset managers, pension groups and sovereign wealth funds are prepared to use their power to push oil and gas companies to tackle climate change, cut carbon emissions, set long-term targets in line with the Paris agreement, boost disclosure on climate risk and hold managers accountable.

According to available data, the number of investor resolutions focused on climate change across all sectors doubled to 42 between the 2013-14 and 2016-17 voting seasons. Oil and gas companies are under scrutiny like never before – this will only continue.

But as Equinor’s chief economist Eirik Waerness pointed out: “We see many examples of weakened co-operation in the world today. We also see more polarisation in the climate debate, with growing activism for change but also protests against the social impacts of change. And, as renewable energy grows, there is more focus on the consequences of new energy projects on nature. In combination, these trends underscore the political complexity of meeting the climate challenge.”