Investing through the downturn [LNG Condensed]

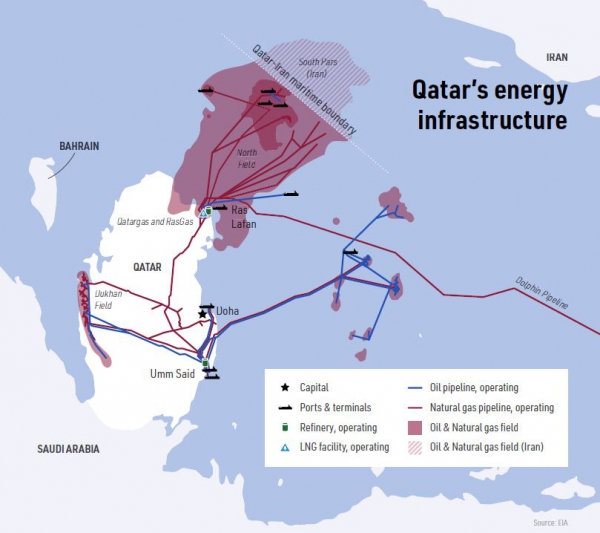

Qatar Petroleum (QP) announced in May that it would cut its capital and operating expenses by 30% this year. This is a larger reduction than many other major oil and gas companies, but QP also said it would move “full steam ahead” with plans to expand its LNG production capacity from 77mn mt/yr to 126mn mt/yr, and that it has no intention of reducing production to weather the period of low prices.

QP does indeed appear to be going full steam ahead. In April, the company reserved capacity at China’s Hudong-Zhinghua shipyard to build LNG carriers for the North Field expansion project in a deal worth more than $3bn. The company is expected to need about 60 new LNG carriers to deliver the fuel from the first phase of the development, the 33mn mt/yr North Field East (NFE) project.

The company also announced in April a start to NFE development drilling, kicking off an 80-well campaign. Some delays have occurred on bids for onshore engineering, procurement and construction contracts, but if there were any expectations that Qatar might slow its expansion program in light of an oversupplied LNG market and reduced demand outlook, these now appear to have been dispelled.

Russia ups its ambitions

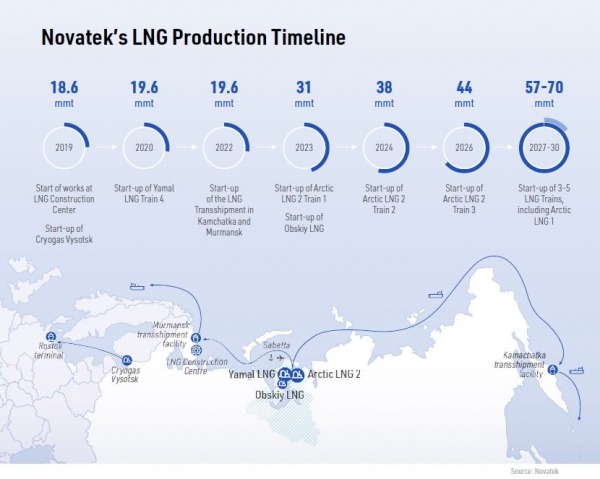

The other country which has maintained and indeed raised its LNG ambitions amidst the pandemic is Russia. In early April, the government adopted a new energy strategy which envisages LNG production rising to 46-65mn mt/yr by 2024 and to 80-140mn mt by 2035, the latter target being an increase from 70-82mn mt/yr.

Moscow has also passed amendments loosening restrictions on which projects are eligible to export gas as LNG. State gas company Gazprom holds a monopoly on the export of gas by pipeline. The new rules mean projects that received licenses after January 1, 2013 will be eligible.

Although Gazprom and state oil company Rosneft both have LNG plans, the new rules, as with the old ones, primarily benefit Novatek, which successfully brought the 16.5mn mt/yr Yamal LNG project on line in phases between 2017 and 2019. A further 0.9mn mt/yr train is expected to come onstream later this year.

The new rules allow the 5mn mt/yr Obskiy LNG project to move ahead, should Novatek sanction the development. This, Novatek believes, could be in operation by 2023, although the company’s chief financial officer Mark Gyetvay said recently the project could be delayed by a year, owing to the 20% reduction in 2020 capital spending announced by the company. Novatek also has further plans on the drawing board, which are expected to deliver 6.6mn mt/yr plus capacity from 2030.

The company’s long-term goal is to produce 57-70mn mt/yr of LNG by 2030, which even at the lower end of the range would put the country on course to meet the government’s long-term energy plan target by 2035.

Although an independent company, with its shares traded on the Moscow and London stock exchange, Novatek’s strategy is closely aligned with the state. The company is leading Russian efforts to develop the ability to construct LNG facilities without the need for foreign technology.

Both Novatek and QP are exploiting huge gas fields, which should keep costs down. Novatek also benefits from Arctic temperatures which means less energy is required to liquefy the gas. QP’s costs will be offset by significant co-production of liquids.

For other developers this means a large amount of competitive new capacity coming to the market amid an uncertain demand outlook.

Spending through the investment cycle

Qatar and Russia’s plans can be seen as spending through the investment cycle, even if the bottom of the cycle has arrived unexpectedly, allowing them to take advantage of low services sector and construction costs. The new capacity will not come onstream for a number of years, when demand for LNG should have returned to its upward trajectory.

However, they are also typical petro-economy strategies. Both rely heavily on oil and gas revenues to support state spending, and neither has managed significant economic diversification. More oil and gas is thus the only option, reinforcing and extending their existing dependence on fossil fuels.

Qatar needs to develop its gas resources to sustain its liquids production. Russia needs to address the uncertainties surrounding European gas demand by reaching new markets.

European gas demand has become more uncertain in the light of the adoption of net zero carbon targets by 2050, and the continued build out of new gas and LNG infrastructure since the Ukrainian gas crises offers alternative non-Russian gas supplies to an increasing number of European countries, threatening Russia’s overall market share.

The announcement in May that Poland has brought on stream a new 70-km gas pipeline in its southeast that forms part of the EU-backed North-South Gas Corridor, is significant. So, too, is the arrival of pipes for the construction of the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria.

Both are part of the infrastructural jigsaw which will enable greater cross-border gas trade in central and southern Europe and eventually link LNG supply from terminals on the Baltic Sea, and proposed ones in Germany, with the Krk LNG terminal in Croatia, as well as Bulgaria with LNG supplies coming in from terminals in Greece. These developments threaten markets formerly fed almost solely by Russian gas.

Slow steamers

Qatar and Russia’s plans contrast with the travails of other developers, who have delayed or reduced their LNG investments. Limited cash flow and a shaky demand outlook mean it has become harder to raise debt and find investors, while the ability to fund investment through internal cash flow has decreased.

But unlike Novatek and QP, the oil and gas majors, which have built up large, globally-diversified LNG portfolios, have a broader range of strategic choices and are not constrained by close alignment to governments dependent on oil and gas revenues.

They have all in recent years diversified their technology investments to some degree in order not to be wrong footed by the prospect of a peak in global oil demand. They have almost all seen their own gas production rise faster than liquids and are eying the possible impacts of electromobility and the much broader electrification of energy supply.

Nonetheless, cost-competitive renewable energy sources have performed well during the pandemic and lie at the centre of the energy transition. When net zero carbon targets by 2050 are taken into account, gas’s role in energy provision starts to become a problem rather than a solution at least in the European context.

Given the current constraints on their own revenues, as a result of low oil and gas prices, rather than go full steam ahead, the majors are slow steaming, a situation when a more fundamental change of direction might be considered.

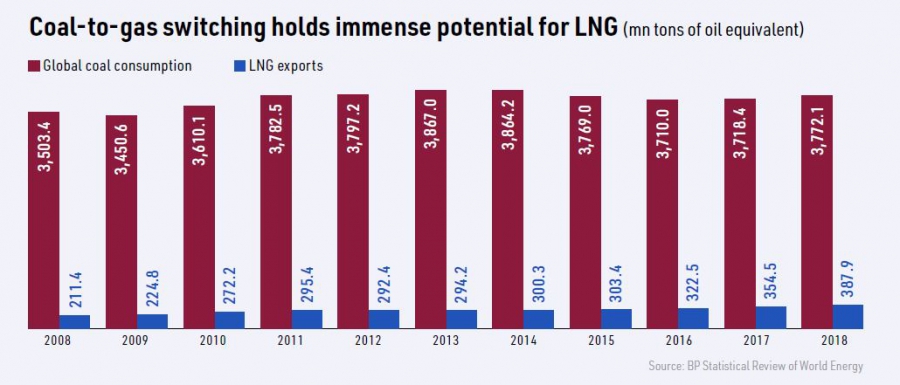

However, these companies are large enough both to survive the current downturn and sustain significant, if reduced, investment. Moreover, gas and LNG sit well within their interpretation of the energy transition -- as a replacement for coal in power generation and for oil in heavy duty transport.

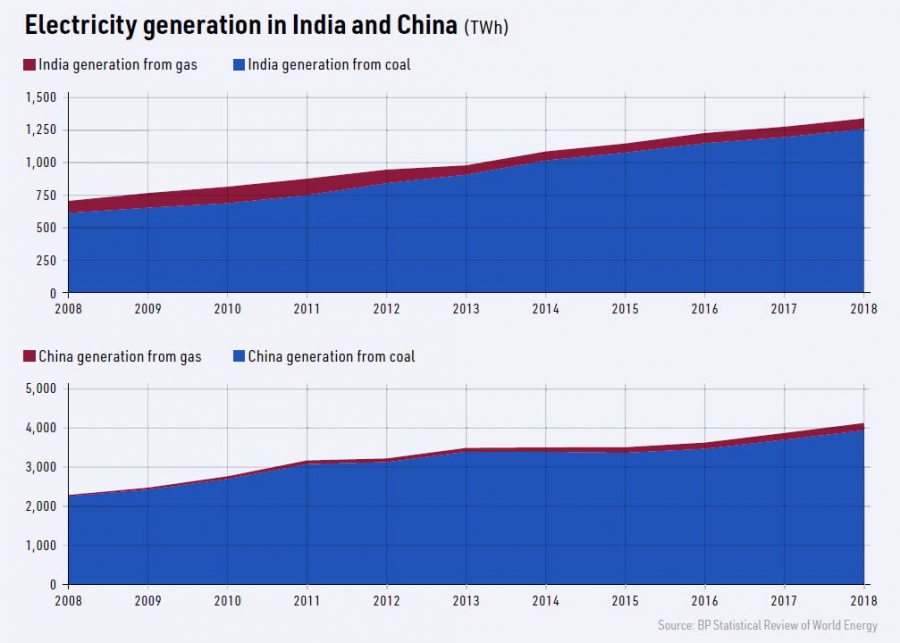

Major economies such as India and China, as well as many other Asian economies, are only in the early stages of gas adoption, a situation which promises sustained market growth for decades to come.

Long-term demand

LNG project investments are generally large, running into multiple billions of dollars, and have to be based on a long-term outlook. A new onshore production facility takes five to six years to build from the financial investment decision and then needs to operate for at least 10 to 20 years, over which time they can be affected by any number of social, political and economic hazards.

Post-Covid-19, a second wave of LNG expansion in the US is now in doubt, as are the timing and scale of a host of proposed LNG developments around the world, for example in Canada, Mozambique and off the coast of West Africa. That Russia and Qatar are determined to go full steam ahead puts pressure on other project developers uncertain of the strength of future demand.

However, some forecasters remain bullish, portraying a world in which LNG demand growth will be more than sufficient for all. In its investor meeting publication, released in April, Novatek showed a forecast from Wood Mackenzie projecting LNG demand growth of 137% between 2018 and 2040. Required liquefaction capacity rises from 314mn mt/yr in 2018 to 740mn mt/yr in 2040, with Asia accounting for the vast majority of incremental demand.

This is plausible based on large-scale gas-for-coal switching in the power sector, particularly in India and China, as well as the expansion of gas use in other sectors such as industry, transport and city use.

The impact of Covid-19 may well be to result in a concentration of supply in the hands of Russia and Qatar and in state-directed companies as oppose to the oil and gas majors or smaller independents. Even so, the possibility of LNG market cartelisation looks remote. Russia has fallen in with Opec not out of choice but necessity, while Qatar left Opec on January 1, 2019, even if both are founder members of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum.

Covid-19 has knocked short-term demand expectations and prices, but the longer-term drivers of gas demand remain in place. It will be those companies both willing and able to invest through the downturn which reap the rewards.