LNG in Transition: from uncertainty to uncertainty

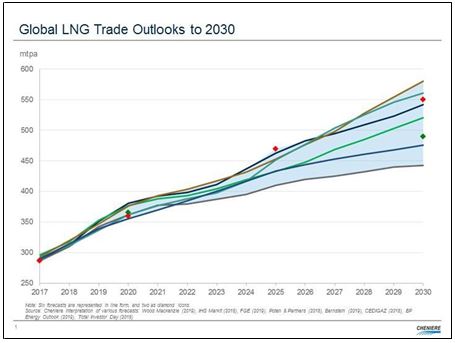

This issue of the Oxford Energy Forum focuses on LNG’s transition from its traditional, more rigid structure to a fully traded commodity. This change is happening during a time of considerable volume growth in the industry, with LNG supply expected to double between 2016 and 2020. The common theme running through this issue is one of uncertainty, be it over the level of demand or supply or the pace of technological advancement along the value chain. An interesting graph provided by Cheniere Energy compares global trade outlooks from eight different sources: consultants, majors, and other organizations. In 2018, global LNG trade was 314 million tonnes (430 billion cubic metres). By 2030, projections vary from 440 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) to 580 mtpa—a difference equivalent to nearly 50 per cent of the 2018 LNG supply level. This reflects the wide range of uncertainties that the LNG market is facing, uncertainties that will be discussed in this issue.

Global LNG trade outlooks to 2030: eight projections

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Even though the LNG chain is disaggregating, the pace of growth of the LNG business is driven by different parts of the chain operating independently. Demand growth in one country can lead to LNG supply commitment for new capacity in another country, or the growth of price hedging tools could enable different buyer and seller price aspirations to be bridged, thus enabling an LNG transaction that was previously impossible.

The market is changing fundamentally and, while there may be little to distinguish many of the new potential supply projects, innovation and technological advancement in each part of the chain is driving costs down. New commercial and sales models are enabling supply projects to meet the requirements of buyers who are themselves operating in extremely uncertain markets that are liberalizing and moving away from long-term cost ‘pass through’ structures. New buyers are entering the market and are able to sign long-term contracts to support the financing of new LNG supply projects, either directly or through aggregators. (An aggregator is defined as a company which purchases LNG from several sources, supplies it to several buyers, and uses its LNG portfolio to its commercial advantage.) The role of traders and aggregators is changing as they take positions along the chain to differentiate themselves, and new companies, including sellers and buyers, seek to trade LNG to gain an additional margin and reduce their risk.

The traditional LNG contract structure where the seller took the (usually oil-related) price risk, while the buyer took the volume risk through long-term take-or-pay offtake contracts, is changing fundamentally. The world today is one of varying contracts, linked through aggregators/traders or directly between buyers and sellers. In 2018, 32 per cent of LNG was delivered on a spot or short-term basis, 25 per cent of which was delivered within 90 days of the transaction date. These percentages will, no doubt, increase further as US LNG, with no contractual destination restrictions, will enable both sellers and buyers to optimize their risks and returns by selling to the highest-value destination, with flexible markets, such as Europe, acting as the balancing mechanism.

The discussion in this issue starts with three papers on LNG supply. Mike Fulwood looks at the current LNG supply position and asks, ‘Is the glut finally here?’ before exploring the factors driving supply and demand over the coming 18 months—concluding that ‘up to the end of 2020, supply growth is expected to exceed demand growth, but thereafter the growth in export capacity is projected to stall, enabling demand growth to start eating away at the excess capacity.’ The article examines the OIES FID Barometer, estimating that the next 12 months may see another 60 to 80 mtpa of new LNG capacity take FID (final investment decision), in addition to the 33 mtpa already taken this year. The article then asks if there could be another glut in 2025/26 and, with a view to the impact on LNG prices, concludes there could be downward pressure on prices for the next 18 months, with prices then firming up, ahead of another potential supply glut and price weakness in 2025/26. What is clear from this article is the uncertainty and volatility that the LNG business will face over the coming five to seven years.

The challenges in bringing an LNG project to FID are examined by Claudio Steuer, who notes that LNG projects are among the most capital-intensive energy projects per unit of energy from well to burner tip. In an industry study, 64 per cent of the projects surveyed faced cost overruns and 73 per cent faced schedule delays. The article identifies the key LNG project development risks and sets out a list of the essential conditions to take FID on an LNG project. The management of risk along the LNG value chain is key, and the article emphasizes that ‘the critical path to reaching FID in LNG projects (rather than the technical aspects of the project development) has become the underpinning of the commercial and financial dimensions of the project.’ The decoupling of the established contractual structure, which results in greater complexity that could lead to project delays, has further complicated this.

The final article in the supply section, by James Henderson, examines whether pipeline gas is a real supply alternative for gas buyers in Asia and whether LNG will remain the major means of gas supply to these hydrocarbon-hungry markets. The article argues that, at least in some countries, pipeline gas can be an alternative to LNG, with China providing the most obvious example of a country that is maximizing its diversification options. Historically LNG imports were contracted from a wide range of LNG suppliers, thus providing supply diversity and hence security of supply, but LNG supply by ship does not come without risks. The Straits of Hormuz and Malacca are choke points that could be blocked, creating security-of-supply concerns for Asian buyers. Pipeline supply diversification reduces perceived LNG risks. China is sourcing pipeline gas from Central Asia, Myanmar, and Russia, but these pipeline gas options are not available to all Asian countries. Countries such as Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan could have pipeline supply options, which, although still risky, could give these important growth economies vital strategic as well as economic diversification.

This issue then examines LNG demand through three further papers. Howard Rogers focuses on Asia and asks if Asian markets will continue to see substantial demand growth or if demand will fall as countries move to renewable sources or keep using cheaper coal which could cause concerns to the LNG companies. The article asks some fundamental questions related to demand in both the new and mature Asian markets and concludes that the growth in Asian LNG demand may be at risk.

Chinese LNG imports, though currently strong, are vulnerable to global trade barriers and lower-than-expected GDP growth. Other demand drivers including the uncertainty of government energy mix policy and the extent to which domestic gas production declines will impact LNG imports. These factors, together with the pace of efforts to reduce both CO2 and particulate pollution and the potential start-up or phase-out of nuclear power, create a high level of uncertainty in the region that, in 2018, imported 75 per cent of global LNG.1

In the second demand-focused article, Anouk Honore focuses on Europe to see what sectors and countries will see gas demand growth and asks a fundamental question: ‘Is there a place for LNG in Europe in the 2020s?’ The article identifies key uncertainties regarding the pace and scale of Europe’s conventional gas production decline, due to fields depleting, or to political or environmental decisions (especially in the Netherlands related to the Groningen field), or both. Where an immediate fall in production could help relieve the potential LNG glut in Europe in 2020 and 2021, it could lead to a tightening of the market in 2023/2024. The disagreement between Russia and Ukraine over the transit of gas through Ukraine also adds uncertainty to gas supply in Europe. Further ahead, after 2025, decarbonization policies could lead to a fall in European natural gas demand.

The article notes that it is the demand for gas in non-European countries that will determine the volume of competitive LNG that is available for Europe, a region that provides the global flexible market for LNG, with demand driven by hub gas prices. Higher pipeline and LNG supply would impact hub prices and would determine the relative attractiveness of the European market compared to others.

Finally in this section, Chris LeFevre investigates the potential for additional LNG demand from the marine and road transport sectors. He notes that, although transportation is attracting a lot of interest as a new market for gas, LNG as a transport fuel faces considerable uncertainty over the breadth, scale, and rapidity of uptake. From 2020, International Maritime Organization rules will ban ships from using fuels with a sulphur content above 0.5 per cent, compared with 3.5 per cent today (unless they are equipped with scrubbers or use low-sulphur fuel). This will create a demand for LNG, but there are alternative means by which ship owners can meet these rules. The article also examines the drivers behind the development of LNG in transport and the regions and sectors where demand is likely to be most significant. Growth in LNG demand in both the marine and road transport sectors is uncertain, but is expected to be steady rather than dramatic, and is ‘not expected to have a major impact on the development of the global LNG market’.

The key changes that are being used by players in the industry in driving LNG’s transition to a globally traded commodity have been in pricing, risk management tools and contractual structures. In the first article in the pricing and trading section, Anne- Sophie Corbeau examines the roller-coaster LNG market of the past 18 months, likening it to a ‘theatre piece in two acts’ in which the market moved from being relatively tight in winter 2018/19, with elevated spot prices in Asia and Europe, to a period of relative oversupply, with Asian spot prices (JKM [Japan Korea Marker]) and European gas prices (NBP [National Balancing Point]) falling towards the level of US LNG exporters’ operating costs. The article considers the implications of the current LNG oversupply for global LNG markets and prices, and the potential future outlook. Examining the role of JKM, the article asks whether Asian buyers will move away from oil indexation and whether LNG pricing will become commoditized (i.e. priced against its own fundamentals), arguing that the path to a fully commoditized market could be a lengthy one.

The growth of hedging tools to manage LNG market pricing exposure has been dramatic. Gordon Bennett argues that liquidity is the measure that determines a market’s ability to provide independent price discovery and transparency and enable risk transfer between market participants. A liquid market, by enabling competition, encourages the ‘most optimal allocation of an asset’.

Even though there are several potential global gas trading hubs, liquidity will coalesce around a few key benchmarks. TTF (Title Transfer Facility) and JKM have emerged as global benchmarks. Whether JKM will remain Asia’s only benchmark is yet to be determined, but even if other benchmarks do develop, JKM’s ongoing rise in volumes and liquidity seems assured. In discussing the rapid rise of the JKM futures contracts, the ratio of the spot LNG to derivative market is 1:1, and this increased liquidity will, in itself, lead to ‘more derivative volume and use for physical indexation’.

Many long-term LNG contracts are bound by strict pricing clauses, and Agnieszka Ason discusses how, with LNG markets in transition, LNG contracts are also changing, creating considerable contracting uncertainty for both buyers and sellers. The article notes that the push towards price flexibility has been a key focus in recent negotiations and changes to LNG contract terms in Asia. One area of importance is the inclusion of more detailed price review clauses in newer Asian LNG contracts and the potential use of price arbitrations in case of disputes. The article notes that conditions for price reviews in new Asian LNG contracts are likely to involve shorter price review periods and the inclusion of triggers; downstream market conditions are likely to become more relevant in future reviews. What is not yet clear is whether the changes in price review clauses will lead to wider changes in Asian LNG contracts.

The last section of this issue examines technology in the LNG chain. Bruce Moore focuses on shipping, an element that is often dismissed as being of lesser importance than other parts of the chain, but as he points out, ‘no ship means no movement of LNG’! Shipping LNG is costly; LNG ships cost approximately double the equivalent oil tonnage while carrying one-quarter of the energy. The availability and cost of LNG shipping can make or break the economics of an LNG deal, whether long, medium or short term. As the sector commoditizes further, shipping, and specifically shipping costs, will become increasingly important, as will maintaining the safety record of the industry. The article challenges the traditional norm that dedicated long-term shipping is required to support the development of the LNG value chain, and examines what is required for the development of a reliable short-term shipping market.

Another area of the chain where technology is having a major impact is liquefaction, and the final two papers focus on this area of the chain. Christopher Caswell discusses liquefaction costs and asks whether new LNG plant costs can be competitive and meet the industry’s aspirational target cost of US$500/tonne. He argues that this cost level is achievable as a stretch goal and challenges teams to look at new technologies and execution methods. He questions the ability to ‘commoditize’ plant design as a means to reduce costs outside North America. He further argues that it is important to look at projects from both a top-down and bottom-up view in order to achieve such low cost levels.

One potential method is to use offshore floating liquefaction (FLNG) units rather than larger, more expensive land-based facilities. In the final technology-related paper, Brian Songhurst asks if FLNG will just be a niche supply source or whether it could become a mainstream technology. The article notes that as well as project development issues, other factors are important. These include weather restrictions for berthing and loading, higher operating costs, the political importance of local content for these high-visibility projects, and the fact that most of the current undeveloped gas reserves lie onshore or close to shore. That said, it is likely, as seen in Mozambique, that FLNG has a role to play as a marginal field enabling tool for longer- term world-scale LNG production.

The editor would like to thank all the contributors to this issue of the Oxford Energy Forum for their fascinating articles, Amanda Morgan for copy editing, and Kate Teasdale for pulling it all together.

I hope you enjoy this issue of the Forum, and if you would like to discuss any of the points it makes, please feel free to contact me (david.ledesma@oxfordenergy.org) or the authors of the articles direct.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.