How to keep the gas flowing in Europe: Interview with Walter Boltz [NGW Magazine]

NGW: You made an important statement during your presentation at Flame 2019: “Voices for an all-electric world are decreasing as issues like resilience, costs, network development, storage, etc. are being more considered.” Can you elaborate on this and its implications?

As the EU climate and energy policy goals were set higher and higher over the past decade, the energy industry started to search for solutions to meet those challenges. For a while the electricity sector representatives presented answers which were at first sight very appealing and easy to understand: "We power everything with renewable electricity and it is as easy as to plug in a toaster. Wind and sun do not cost anything and are available in almost unlimited amounts."

On the other hand, the gas sector has significant issues in overcoming its fossil-fuel image. So, for many people natural gas was not a credible solution for the future energy system. The gas sector responded with the ‘gas as a transition fuel’ idea, which looked appealing for the short term but was a dangerous concept because you accept that after the transition there is no need for gas!

I think the change in mindset in the energy sector itself began when people realised that the ‘all-electric’ concept has several unresolved problems, with no apparent solution likely to appear until perhaps towards 2050.

- Long-term, seasonal storage of electricity.

- Long-distance transportation of huge amounts of electricity. Building high-voltage lines in sufficient quantity by 2040 to 2050 seems to be a challenge too far.

- Where to put all the wind power plants? They have to be out of sight to be acceptable for the public, but close enough to demand in order to keep costs manageable.

- Resilience and growing complexity of a highly decentralised and digitalised system. Some major generators seem unable to keep their websites and simple commercial software safe from hackers and distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks. Who believes it will be possible to make the operation of very complex electricity systems, with millions of small generators and highly complex demand side management solutions, sufficiently secure? This becomes even more important if this is the ONLY energy system we have!

So over the last two years many experts have accepted, that an ‘all-electric’ energy system with mostly (90% +) renewable electricity may be impossible to achieve by 2050.

Whereas the gas system can offer decarbonised solutions to some of the problems, and the gas sector can do this with considerably lower cost than an all-electric option.

NGW: You also said that what is needed is a new narrative for the future energy system and the contribution of the existing gas infrastructure. Again, can you elaborate on what you have in mind?

We need a future energy system that is almost carbon-free, and we need this sooner rather than later. And when I say energy system I mean all energy sectors: electricity, heating, transportation, and, partly also, industry.

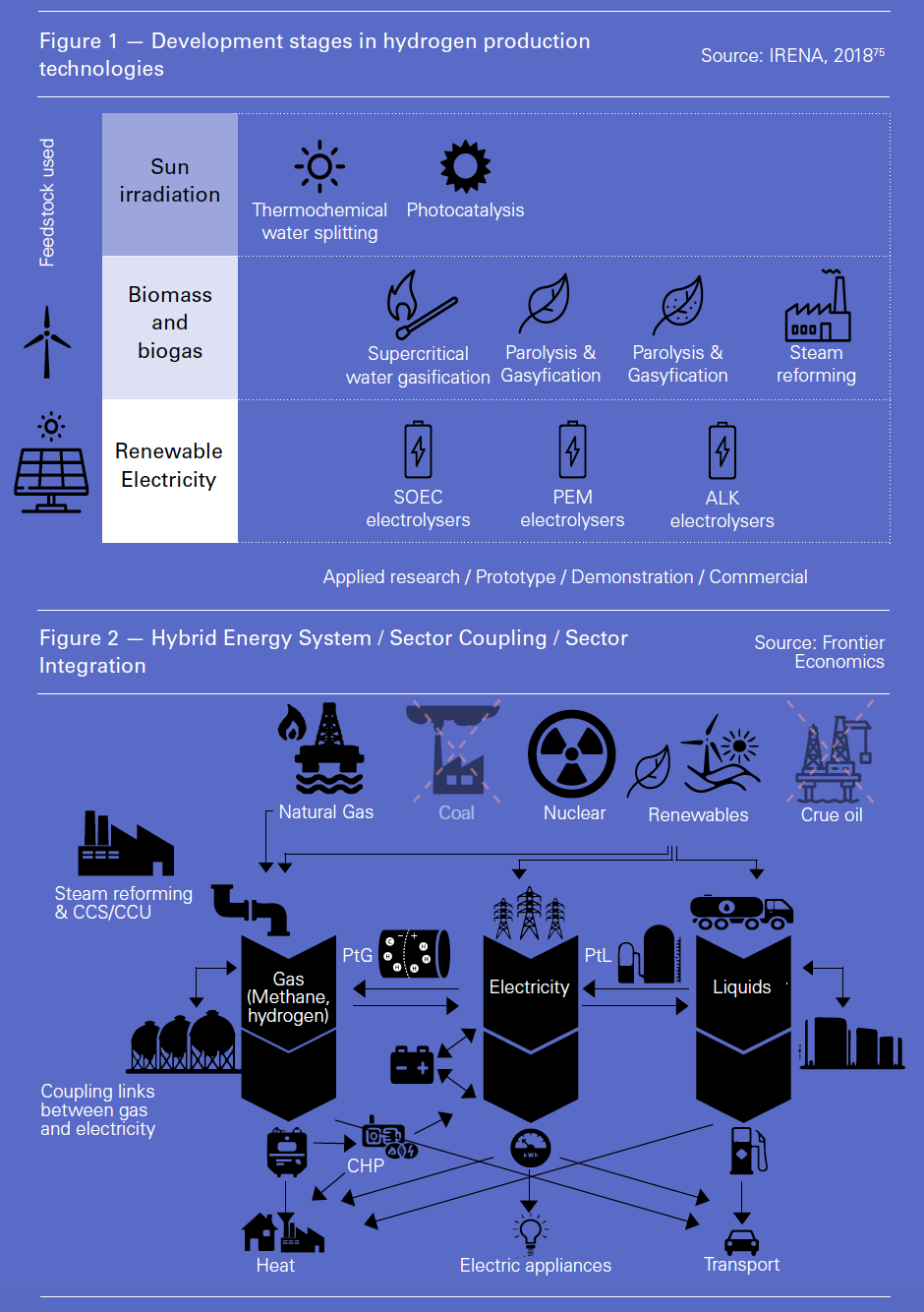

It is clear that the electricity network, including existing renewable generation capacities, cannot provide all energy needs of European society. However, we also have an existing, well developed and mostly paid for gas infrastructure (Figure 1) which offers opportunities for our objectives if we employ it wisely. Gas has to become eventually fully decarbonized if it wants to play a long-term role. There are available technologies but costs need to come down and pilot projects need to become much larger.

To make this happen it is necessary that we stay technology-neutral as we do not know which route will be the most efficient one: eg hydrogen from power to gas (P2G), blended in the gas system, or hydrogen from pyrolysis of natural gas in separate networks, or steam methane reforming and carbon capture and storage and so on (Figure 2).

The gas infrastructure – gas pipelines and storage – exists and can help solve some of the problems we are encountering with the renewable electricity system. Gas infrastructure can be used to store renewable energy, in the form of hydrogen produced from P2G in gas storage. The existing pipelines can transport vast amounts of energy efficiently over long distances, and so on.

NGW: What investments are needed to ensure that the existing gas infrastructure can serve as the backbone of the future hybrid energy system?

For using the gas infrastructure in the future, we only need limited additional investments. Concepts such as the hybrid energy system sector coupling or sector integration are all very similar and are possibilities to achieve this. We need some big pilot projects in P2G facilities, pyrolysis and biogas production; we need applied research and development as many of the technologies exist but need large scale applications to drive down costs. And we need some experiments as we have to learn the best (most economical) ways to use these technologies.

The infrastructure operators need to invest in conversion facilities, metering and gas quality management, but these are limited compared with the overall infrastructure costs.

Many ‘investments’ are needed in organisations and coordination as the transmission system operators’ jobs will become more varied and complex if we want to retain the EU gas market and at the same time allow different gas qualities to coexist. The transmission system operators (TSOs) will be the ones responsible for managing these differences without limiting gas trading.

And finally we need to consider the financing systems for such investments and for the additional system costs incurred with such a development. How these costs are recovered through the regulatory system and who should pay for them - small household customers, industry?

NGW: Who is going to do this and how can we ensure this is delivered?

I believe the key role is for TSOs as infrastructure ties everything together and they are – at least initially – the best market actor to do this, since they are not in competition and will find it easier to make many of the early investments in facilities and infrastructure, if the cost recovery and socialisation of these costs are properly regulated.

As we have seen in renewable electricity it is quite expensive to motivate market players to take big risks, such as building the first few off-shore wind farms or photovoltaic installations. Practically speaking the public sector had to offer such high rates of return – in the form of feed-in tariffs – that the risks and uncertainties were more than adequately covered. And this has resulted in very high burdens for energy customers for many years to come.

With TSOs on the other hand we have a ‘tried and trusted’ mechanism of regulated tariffs that enable an efficient socialisation of costs. The TSOs need recovery of actual costs only and not the lure of potentially double-digit profits to start them on such innovative projects.

To make this happen we need some smart regulation and a few ‘tweaks’ in regulatory rules, eg some flexibility regarding unbundling rules, and so on. This most likely needs EU legislation to make this possible in a harmonised way across the EU.

NGW: You talked about uncertainties and flexibilities. Can you elaborate?

The potential for renewable energy generation – solar, wind, hydro, agricultural waste and so on – and energy storage (in geological formations), as well as existing electricity and gas capacity and congestion are very different across Europe. Therefore, we need flexibility regarding financing possibilities as well as regulation.

For example, in some regions it might make sense to generate energy in off-shore wind farms and transport it via gas pipelines, instead of electricity cables, to industrial centres that might not be close to the beach or where tourism is a consideration.

The existing regulatory system, especially the unbundling rules, clearly says that system operators are not allowed to generate/produce energy. Any sector integration technology would be a generation/production facility. Therefore, the possibilities for TSOs and distribution system operators to contribute are limited. However, if the market does not deliver, we need to talk about the flexibility that allows/obliges those regulated entities to temporarily step in, but under regulatory supervision.

At a time when we do not yet know the ultimate, most efficient, technology it is important to leave some room to try things out while we learn. The uncertainties of whether this is possible and how, need to be reduced.

NGW: Given that the answer to Q1 applies globally, is this a European system or does it need to be more global?

I think the idea of a hybrid energy system is something that would work everywhere, but, as we already face different situations in different regions in Europe which call for flexibility, this will be even more the case on a global scale.

However, if we are talking about decarbonisation of gas I firmly believe that we need to discuss whether in the future we want to import natural gas and decarbonise it in Europe or whether we want to import already decarbonised gas in whatever form.

In the US we see a less ambitious and less ‘dogmatic’ approach towards decarbonising the energy sector. There they call it the ‘integrated energy system’ – while in Europe we call it a ‘hybrid system of decarbonization’ .

If you have sustainable and decarbonised energy as an objective, without too rigid targets, it becomes easier to manage than if you have the 2050 targets in absolute terms.

NGW: If Europe goes it alone, will it be disadvantaged against other competitor economies such as the US and south and southeast Asia?

If we go it alone we will not have that much impact on climate change. So yes, from this perspective it will be a big disadvantage. However, I cannot imagine that Europe will go it alone, but it looks as if we will be early movers.

From the economic point of view, the answer depends on the time-frame you look at. In the short run, we will have higher energy-related costs, but in the mid and long run I am confident that the costs will significantly decrease.

However, I think it is important to not look at the cost of energy in isolation, as the climate change challenge affects every single aspect of our society, as we need to take into consideration aspects such as effects on jobs, health, air quality, and so on.

Europe is a huge market and will remain an attractive destination market for producers from all over the world. It is up to Europe as an entity, or the European Union, to decide which standards or offset products should be imposed at the border. For exporters, this question will have to be assessed carefully. This is one of the areas where incentives might be needed.

NGW: Decarbonisation calls for urgent action, but it has to have a global reach to be effective. The biggest polluters are in North America and in Asia. Can Europe convince them to adopt this common model? If not, will this diminish its effectiveness in terms of impact on climate change?

If we want to reach climate goals, we have no choice but to convince at least the biggest polluters outside Europe – China, US, India/SE Asia – to join. Otherwise all our actions will be to no avail. But we should not underestimate the effects of good examples. Many of these economies believe more climate protection means less economic growth and welfare. If we are able to show that this is not the case and that you can have a prosperous and environmentally friendly, fully decarbonised, energy sector, this will be an important example and will have a strong impact on these countries.

NGW: Public perception is running fast and may be ahead of what can be practically achieved without major disruption and cost. How can this be managed?

We need a straightforward narrative and fact-based evidence explaining complex relations. The younger generation has understood what is at stake. This is not to scare people unnecessarily, but this is the reality we need to face. People are not stupid but they tend to forget about things they feel uncomfortable with. Therefore, we need to improve efforts regarding the knowledge of society about not only climate change but also the energy system and what this means for our everyday life. It is the backbone of our modern society with smartphones, social media, escalators and cashpoints everywhere as well as central heating, public and individual transport, remote controls, etc.

NGW: What is the timing of implementing the Hybrid Energy System?

We have to start thinking and planning now. We first need bigger investments in pilot projects. We also need to introduce organisational measures now, for example a green gas labelling system, guarantees of origin for green gas, standards for gas quality, and so on.

The bigger rollout needs to start around 2030 so that we can have the “green gas system” in place by 2045 to 2050