Indonesia: the next big LNG importer? [Gas in Transition]

Indonesia was the world’s largest LNG exporter in 1990, with sales of 20.35mn mt, accounting for 38.4% of global trade. Its share of the market declined steadily from the 1990s, although it only lost the title of largest LNG exporter to Qatar in 2006. With no respite from the fall in sales, by 2021, it had dropped through the ranks of LNG exporters to be placed eighth.

In part because of the constitutional stipulation that domestic needs have priority over the export of commodities, Indonesia has an ambivalent attitude to exporting gas, whether as LNG or piped to Singapore and Malaysia. Opponents of exports argue that gas should be used at home to manufacture products for export, rather than exported as a raw material to industrial competitors.

Falling oil production – down 3.1%/year from 2011 to 2021 -- is another reason why domestic use of gas has been prioritised. A large amount of Indonesian electricity was produced from oil until relatively recently, so switching to gas-fired generation was seen as a way of freeing up oil production for use in higher value applications such as transport.

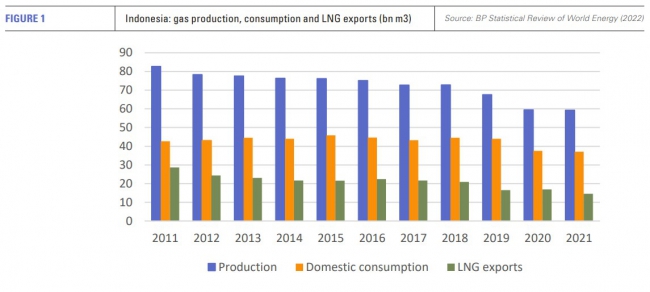

These factors have led to increasing restrictions on LNG exports, with overseas sales declining steadily. According to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2022, LNG exports almost halved from 28.7bn m3 in 2011 to 14.6bn m3 in 2021.

Falling gas output

While the domestic market obligation is often cited as the rationale for restricting LNG exports, there is a more fundamental reason for the shift from overseas sales. Indonesian gas output has been falling for years, and there are few signs that the trend will be reversed. According to BP’s data, Indonesian gas production fell from 82.7bn m3 in 2011 to 59.3bn m3 in 2021.

It is less that domestic gas use is preferable for economic or constitutional reasons, and more that there is insufficient gas to physically supply both the domestic and export markets.

The fall in output is due in large part to constrained private and especially overseas investment in the gas industry and wider energy sector. Always problematic because of the country’s opaque legal and regulatory environment, international investment has never fully recovered from the unilateral contractual changes imposed by Jakarta during the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

The fall in output is due in large part to constrained private and especially overseas investment in the gas industry and wider energy sector. Always problematic because of the country’s opaque legal and regulatory environment, international investment has never fully recovered from the unilateral contractual changes imposed by Jakarta during the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

The impact of low investment has been felt throughout the gas chain. A lack of exploration spending, for example, is one of the main reasons for the precipitous fall in Indonesian natural gas reserves.

According to the Directorate General of Oil and Gas, proven and potential reserves totalled 4.1 trillion m3 in 2016. By 2021, the total was estimated at less than 1.7 trillion m3.

Project delays

A lack of capital is not the only problem. Even projects that have secured investment can remain mired in delays as a result of regulatory and other issues.

Take, for example, the offshore Masela Block in the Arafura Sea. Japan’s Inpex won an open bid for the block in 1998, with Anglo-Dutch major Shell subsequently acquiring a 35% stake.

As currently envisaged, the $20bn project includes development of the 359bn-m3 Abadi gas field, a 9.5mm mt/yr onshore LNG plant backed by a sales agreement with the state electricity company PT PLN, gas pipelines to supply 4.2mn m3/day to the domestic market and condensate production.

Yet despite the value of the project, Masela has suffered a series of setbacks, including switching from a floating LNG plant to an onshore facility, Shell’s decision to withdraw from the project in 2020, and the requirement to add expensive carbon capture and storage equipment.

In the latest bid to kick-start the project, the Japanese government in July offered financing so the state energy company PT Pertamina or Indonesia’s sovereign wealth fund could buy Shell’s stake in the project. While Masela was at one stage targeted for operation by 2027, Inpex now says it is scheduled for operation in the early 2030s.

Reduced exports have not increased gas availability

Low exploration and development spending combined with implementation delays have resulted in falling gas output. This, in turn, meant the near-halving of LNG exports over the last decade failed to release large amounts of gas for use in the domestic market.

In fact, Indonesian gas consumption fell from 42.7bn m3 in 2011 to 37.1bn m3 in 2021. Over the same period, gas’s share of total primary energy supply fell from 22% in 2011 to 17% in 2021, according to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR).

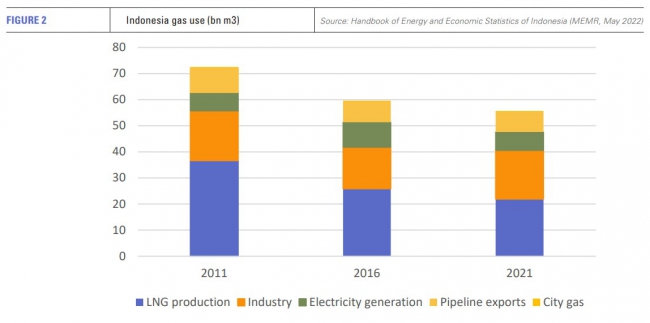

Indonesian gas use is concentrated in the industrial and electricity generation sectors. In 2021, it accounted for only 0.21% of residential and 1.66% of commercial sector energy use, and for only a negligible amount in transport, according to MEMR data.

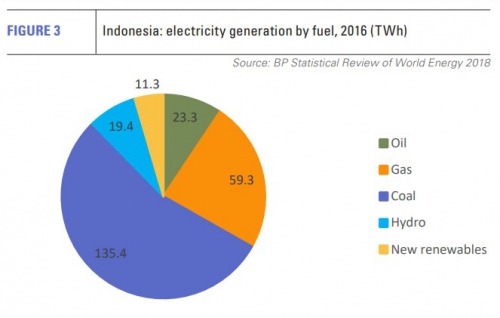

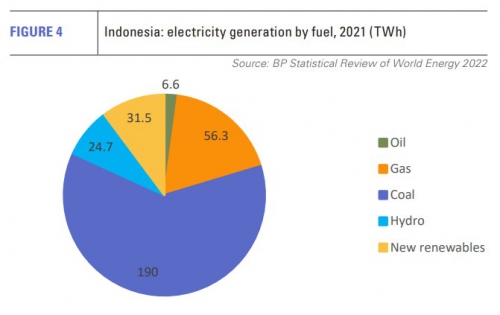

By contrast, it accounted for a third of industrial energy use in 2021, most gas being used in the metal, fertiliser and ceramics industries. In addition, at 56.3 TWh, gas contributed 18% of total electricity output in 2021. This was not dissimilar to the 59.3 TWh of electricity produced from gas in 2016, although in that year gas accounted for almost a quarter of total electricity output.

The declining share of gas-fired electricity generation has largely been compensated for by increasing coal use. Coal-fired generation reached 190 TWh in 2021, and accounted for 61.4% of total power production compared to 54.5% in 2016.

The trend in coal production is in marked contrast to that of gas over the past decade, with output rising from 353.3mn mt in 2011 to 613.9 million mt in 2021. A substantial part of the production is exported – 70% in 2021 – but domestic coal consumption also rose by two-thirds over the decade, with an increasing proportion going to power generation.

Coal use by generators increased from 45 million mt to 112.1mn mt between 2011 and 2021, with the proportion of domestic coal consumption used to generate electricity rising from 57% to 84% over the same period.

Coal or climate?

Coal use has underpinned burgeoning growth in Indonesian electricity consumption, but recently-announced government plans stipulate that greenhouse gas emissions must fall by between 29% to 41% by 2030, while electricity demand is projected to increase by 4.4%/year to 2030. Addressing both climate targets and rising power demand will only be possible with much reduced coal use.

This begs the question as to what will replace coal? Based on performance to date, renewable energy is unlikely to be the answer in the near to medium term.

Indonesia has substantial renewable energy potential, estimated at 94.3 GW for hydropower, 207.8 GW for solar, 60.6 GW for wind, 28.5 GW geothermal and 18 GW of ocean energy. However, progress in deploying capacity of any type has been disappointing.

The hydro, geothermal and ocean energy options have long lead times and are capital intensive. Solar and wind are less expensive and have much shorter development times, but together accounted for only 0.12% of total primary energy supply in 2021. Among the issues hindering solar and wind projects are, as usual, lack of capital, problematic power sales tariffs, and difficulties securing project sites in what is a densely-populated country.

It has been proposed that imports of solar electricity could kick-start the supply of renewable-based power to Indonesia, for instance through the proposed Australia-Asia Transmission Link. But operation of the 20-GW project does not seem likely in the near to medium term, while Singapore is first in line to receive power from the project.

Step forward LNG

If a substantial amount of coal-fired generation is to be displaced in the relatively near term, a substantial increase in gas use will be needed as the bridge fuel during what could be a long transition period to a renewable-based energy system. Much of that gas will have to be imported.

State energy body SKK Migas has claimed that domestic gas output could double to 124bn m3 by 2030, but the legacy of a decades-long lack of investment in the gas industry means there is little likelihood that this will be achieved. The prospects for gas imports via pipeline are equally low, if not lower, over the next decade, so the answer seems to be LNG imports.

Some facilities capable of importing LNG are already operational, with existing liquefaction plants such as Arun having been reconfigured to import the fuel. A substantial amount of new capacity is also operational, under construction or planned.

The projects are primarily intended to move domestic gas around an archipelago nation where pipelines are often infeasible, but LNG is also being imported. Most of the new-build projects are floating storage and regasification units and most of the projects serve Java, but facilities are also being developed off the coast of other islands, including Sumatra and Bali.

How much LNG Indonesia will actually import will largely depend on how serious the government is in reducing coal-fired generation to meet its climate targets. This is especially so given the substantial current price gap between coal and LNG.

However, the country hosts a large amount of under-utilised gas-fired generation capacity, much of it accessible to operational or planned LNG import terminals. Assuming both sufficient political will to address climate change and a fall in the difference between coal and LNG prices, the market is potentially substantial.