India: striking an energy balance [NGW Magazine]

The International Energy Agency (IEA) released its first in-depth review of India with its 2020 Energy Policy Review in partnership with NITI Aayog, a government think-tank that was established to achieve sustainable development goals.

The IEA says the review, published January 10, highlights India’s many success stories, including major investments in distribution to bring electricity to more people. But it also identifies the challenges that India will face in its quest for sustainable development.

Introducing it, NITI Aayog special secretary Shri RP Gupta said the review would help the government meet its energy objectives “by setting out a range of recommendations in each energy policy area.”

The IEA executive director Fatih Birol said the energy choices that India makes will be “critical for Indian citizens as well as the future of the planet.”

And he is not exaggerating. With a population of 1.4bn – and rising – and one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies, India will be a major actor in future global energy markets. The report says its demand for energy is set to double by 2040: electricity demand may triple while oil demand is expected to grow faster than that of any other major economy. These make it all the more urgent for it to improve its energy security.

The IEA welcomed India’s plans for large-scale renewable energy auctions and attract foreign investors to its oil and gas markets.

India’s economy has hit a rough patch, and the World Bank has cut India’s growth for the financial year 2019 to 2020 to 5% from 6% – the lowest in 11 years. Sluggish consumer demand and failing manufacturing sector are indications of tougher times ahead.

As a result, the Eurasia Group ranked India as fifth highest geopolitical risk in its 2020 list. It said the government’s ‘social’ policies at the expense of an economic agenda were affecting also its foreign policy image. These may lead to intensified communal and sectarian instability, as well as foreign policy and economic setbacks in 2020.

Below-forecast oil and gas output owing to operational difficulties and delays in drilling meant that oil and gas import dependence rose in 2019. As well as draining state resources, they also make the country more vulnerable to external market shocks.

Key findings

- India achieved strong growth in renewables. These now account for almost 23% of the country’s total installed capacity.

- India has done well with energy efficiency improvements, which helped avoid 15% of additional energy demand – in terms of oil and gas imports – and reduced air pollution as well as contributed to a drop of 300mn metric tons of CO2 emissions between 2000 and 2018.

- India’s oil demand growth is set to overtake China’s by mid-2020s, priming the country for more refinery investment.

- Domestic oil production is expected to rise only marginally, making India more reliant on crude imports and more vulnerable to supply disruption in the Middle East.

- India aims to increase the share of natural gas in the country’s energy mix to 15% by 2030, from 6% in 2019.

- India is making progress towards its target of 175 GW of renewable capacity by 2022, with a new target to achieve 450 GW by 2030, helping the country to meet its Nationally Declared Commitments.

- Around 750mn people in India gained access to electricity between 2000 and 2019, reflecting strong and effective policy implementation.

The IEA’s recommendations include stronger regulators to ensure non-discriminatory access to infrastructure; moving from state allocation to market pricing; and further rationalisation of energy subsidies. And key perhaps is to co-ordinate energy policy across government in a national framework.

Energy minister Dharmendra Pradhan said the review vindicated the significant advances made by the country in realising its vision, including its energy transition.

National Energy Policy

The review says: “The draft National Energy Policy (NEP) by NITI Aayog, now under consultation, is an excellent framework and should be adopted swiftly to guide policy-making, implementation and enforcement across central and state governments.”

It recommends that India should adopt the draft NEP, prepared by NITI Aayog in 2017.

Its key objectives are: access at affordable prices; improved security and independence; greater sustainability; and rapid economic growth.

The NEP identifies energy as a key input towards raising the standard of living of Indian citizens. Its main aims are:

- Universal electrification by 2022; manufacturing to contribute a quarter of India’s GDP, from a sixth in 2017; oil imports to fall by 10%; and 175 GW renewable energy;

- A 35% reduction in emissions intensity in the next decade in comparison with 2005, and more than a 40% contribution from non-fossil fuels in the electricity mix;

- Energy security by making the various ministries that set their own sectoral agendas work together more closely.

It also identifies key global developments that require policy clarity:

- The move away from fossil fuels;

- Oversupply in the oil and gas markets and so low prices;

- Abundant natural gas for years to come;

- Maturity of renewable energy technologies;

- Climate-change concerns.

A government priority is to ensure its citizens have access to sustainable and clean energy.

In the light of the energy challenges faced by the country, and global energy-related developments, the NEP sets out the national energy objectives and the strategy to meet them over a medium term time-span to 2040.

Primary energy demand

According to BP’s Energy Outlook 2019, India’s share of total global primary energy demand is set to roughly double to about 11% by 2040, underpinned by strong population growth and economic development. India is expected to account for more than a quarter of net global primary energy demand growth between 2017-2040, of which about two fifths will be met by coal. So the country’s CO2 emissions will grow 116% by 2040.

Industry sector is the largest energy consumer in India: in the last decade, total final consumption (TFC) rose by 50%, with all sectors growing (Figure 1).

Nevertheless, the Economic Survey of India (ESI) for 2018-19 found that per-capita energy use – 0.6 metric tons/yr of oil equivalent – is only a third of the global average. Even though India accounts for about 18% of world’s population, it uses only around 6% of the world’s primary energy.

This is confirmed in the opening statement in India’s NEP, which says that energy is a key input towards raising the standard of living of citizens of any country.

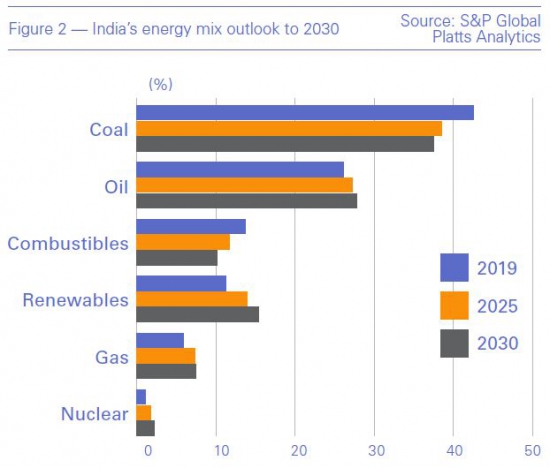

India has steadily been using more electricity and this trend will continue, but fed less by coal (Figure 2) and more by renewables.

Figure 2 reflects the rise in renewables matching the decline in coal. But gas demand is not expected to grow rapidly and its share will still be below 8% by 2030, owing to infrastructure bottlenecks.

The ESI concluded that “India’s economic future and prosperity is dependent on her ability to provide affordable, reliable and sustainable energy to all her citizens.”

Coal

Coal is still king because it is so cheap: produced mostly domestically, it also provides employment. Coal India has over 300,000 people on its payroll.

According to BP, coal’s share in India’s primary energy consumption will drop from 56% in 2017 to 48% in 2040. But in real terms it will more than double, from 424mn toe in 2017 to 917mn toe by 2040.

The US Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) International Energy Outlook for 2019 (IEO2019), predicts that India will lead global growth in industrial consumption of coal by 2050, driven largely by growth in the country’s steel and cement sectors.

However, there is one success story. Coal is meeting a shrinking share of the power market thanks to renewables.

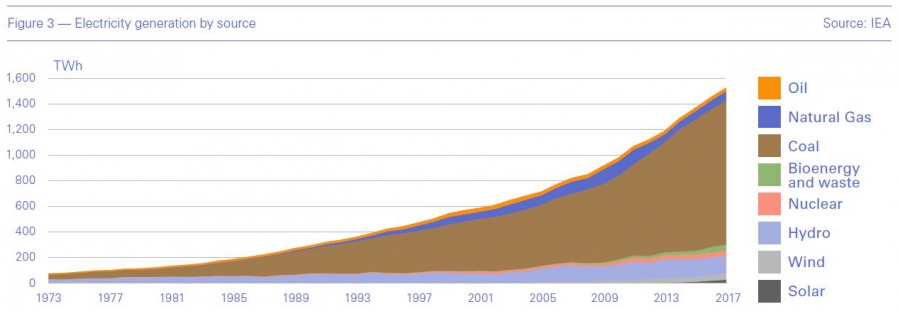

But coal still generates 72% of India’s electricity (Figure 3). This is why coal will continue to be integral to India’s economy during the next two decades.

Electricity generation went up by over 90% during the decade to 2017, mainly from coal. IEA’s Review asserts that an efficient coal sector is critically important not only for electricity generation, but also for industrial development in areas such as steel, cement and fertilisers.

Oil

According to the IEA, India’s oil demand is expected to reach 6mn b/d by 2024 from 4.4mn bls/d in 2017, making the country a key driver for global oil demand growth. It ranks third in terms of global oil consumption after China and the US. It is also the fourth‑largest oil refiner and a net exporter of refined products.

But with over 80% of its oil needs shipped through the Straits of Hormuz, the Indian economy is and will become even more exposed to risks of supply disruptions, geopolitical uncertainties and the volatility of oil prices. As a result, the IEA recommended that India expands its oil reserves.

India has prioritised reducing oil imports in a few years to two-thirds – from 85% today – increasing domestic upstream activities, and diversifying its sources of supply. It wants to spend more in overseas fields in the Middle East and Africa.

Natural gas

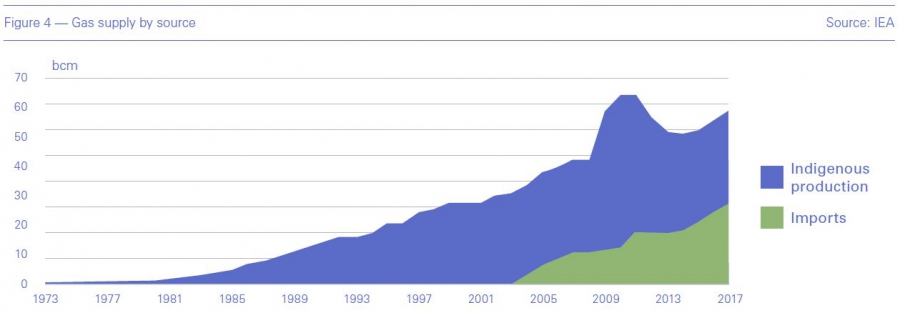

With domestic natural gas production declining by 1.5% in 2019, gas import dependence exceeded 51%, significantly up from 46% in 2017 (Figure 4).

According to BP’s Energy Outlook, demand will grow from 45bn m³/yr in 2017 to 185bn m³/yr by 2040. But this will comprise only a small part of the overall mix, with the gas contribution increasing from 6% in 2017 to 8% in 2040.

According to the review, the government wants the share of natural gas to reach 15% of the total by 2030, from 6% in 2017. This is quite ambitious, but it would allow India to improve the environmental sustainability and flexibility of its energy system. However, infrastructure hurdles and high prices are making this difficult to achieve.

But ultimately the problem for gas is economics – LNG imports are simply too expensive. During the first half of 2019 spot LNG price averaged $5.32 per mn Btu and Brent-linked long-term contracts averaged $8.82 mn Btu. The domestic gas price was $3.69 per mn Btu. The price of coal over the same period averaged $2.75 per mn Btu. This explains why coal in king in India. As a result, it is difficult for coal-to-gas switching to happen without specific government policies.

Pradhan has confirmed the importance of gas to India. He said that India is becoming a gas-based economy and developing indigenously produced biofuels, quite apart from implementing renewable energy and energy efficiency measures, that can potentially achieve India’s much-needed carbon emission reductions.

He also said: "We are aggressively working to build City Gas Distribution Network covering more than 400 districts of India. This network will serve 72% of India's population with cleaner and affordable gas over more than 50% of India's geography." He added "I am confident that these initiatives in the gas sector would bring about a transformative change in India's energy landscape."

The role of gas has grown in India’s residential and transport sectors but has fallen in power generation, where imported natural gas remains squeezed by cheap renewables and coal.

Increasing domestic gas production has been a key government priority, but with output coming below forecast levels over the past few years, India has to rely on increasing imports of LNG. It has five operating regasification terminals. Projects under construction could result in up to 11 additional terminals over the next seven years. But these and the required pipeline infrastructure are facing serious challenges.

The IEA has called for a liquid gas market as a means to overcome these problems: the move from gas allocation and multiple pricing regimes to the creation of a hub will allow domestic gas and LNG imports can be used in the most efficient way and competition can flourish.

But ultimately, if natural gas is to gain a longer-term foothold in India and in emerging markets, the cost gap to competing fuels, including solar, wind and coal, must be kept as low as possible.

Renewables

Renewables - solar, wind and hydro - driven by increasingly low prices, met about 70% of the growth in India’s demand for electricity during the first half of 2019. The ESI found that globally, India stands fourth in wind power, fifth in solar power and fifth in overall renewable power installed capacity.

The prime minister Narendra Modi announced at the UN climate summit in September that India will increase renewable energy capacity to 450 GW, and even though he did not give a timetable, other reports indicate 2030. The current target is to achieve 175 GW by 2022. At the end of 2019 India achieved 84 GW combined solar, wind and biomass capacity. These are ambitious targets, and even if India does not achieve them fully, the potential benefits in terms of reduced coal consumption and emissions can be enormous.

Large-scale auctions have contributed to more renewable energy development at ever cheaper prices. But government targets are quite high given the lack of interest from financial institutions as well as investors. Other capital strategies are needed to fund change. The ESI has said that if India is to achieve its renewable energy targets it will need $30bn annual investment for the next decade.

If achieved, India’s new targets could mean that in the longer-term electricity demand could be met mostly by non-fossil fuels, especially if combined with storage.

Storage is needed to reduce dependence on coal-fired power generation, which still provides the required baseload. With India’s focus on renewable energy and electric mobility, domestic energy storage solutions are set to play a crucial role in the storage sectors’ success.

In addition, with no common standards for open market trading between states, India’s lack of a national energy market, supported by policies and regulatory frameworks is becoming a serious obstacle.

But given the low cost of renewables and the fact they reduce the need for expensive energy imports, despite challenges, growth of renewable energy is expected to be rapid.

Not surprisingly, the sector has been at the centre of policy attention and the Indian government has been focusing on measures to help unleash its full potential.

Carbon emissions

During the last ten years India’s energy and emission intensities fell by more than a fifth. Its per-capita emissions today are 1.6 metric tons (mt) of CO2, well below the global average of 4.4 mt, while its share of global total carbon emissions is about 6.4%.

This is reflected in the Climate Action Tracker report on India. It states that the country is on course to achieve its 2 °C-compatible NDC target under the Paris Agreement.

Because of its heavy dependence on coal, India’s power sector is responsible for half of India’s CO2 emissions.

According to a Carbon Brief report, growth in India’s carbon emissions slowed down sharply during the first eight months of 2019, going up only by 2% and putting the country on track to its lowest annual increase in nearly 20 years.

The main reason was a slowdown in the expansion of coal-fired electricity generation, with renewable output surging and demand growth slowing.

According to Carbon Brief, an added benefit from this is that slower growth in coal-based power generation is also benefiting the India’s air quality efforts.

Implications

Pradhan recognises that energy security is paramount importance and said that India has “made great strides in recent years towards achieving universal access to modern energy,” adding that “we have more ground to cover and also to ensure that the initiatives are implemented for achieving universal coverage in the country."

Pradhan said that in order to achieve this, an estimated investment of $100bn has been lined up in oil and gas infrastructure. This includes a gas pipeline network that, according to the minister, will soon be covering the length and breadth of the country. India has just approved $774mn funding for a 1,656-km natural gas pipeline to link eight states in its northeast, to be completed by 2023, as part of a national gas grid being built to connect remote locations.

However, import dependency and the high cost of LNG are limitations that must be overcome if gas is to gain ground at the expense of coal.

Energy security has now become a prime policy priority for the Indian government. Pradhan said: "We have taken note of IEA's recommendation for reinforcement of India's oil emergency response policy. Enhancing international engagement on global oil security issues is already an active goal being pursued by my ministry. Energy has become an essential commodity in our bilateral trade engagements with several key trading partners and in positioning India as an important strategic player in the global energy landscape."

India now has the institutional framework it needs to attract more investment for its growing energy needs, including for R&D and its ‘Made-in-India’ manufacturing initiative. This is becoming increasingly important, as energy demand and investment needs increase in line with the country’s economic expansion.

The key factors in India are keeping pace with growing energy and electricity demand, energy security, energy access, meeting health, poverty, and education needs and air quality in major cities. These take priority and climate and the environment follow.

India has some of the world’s most ambitious renewable energy targets, and the government and country are striving to deliver on those goals, as well as to accelerate the transformation of India’s energy sector. But whether it can realise its energy potential will depend on how well it copes with the economic and social headwinds.

_f900x314_1579515164.JPG)