Global hydrogen demand is rising, but lags behind expectations [Gas in Transition]

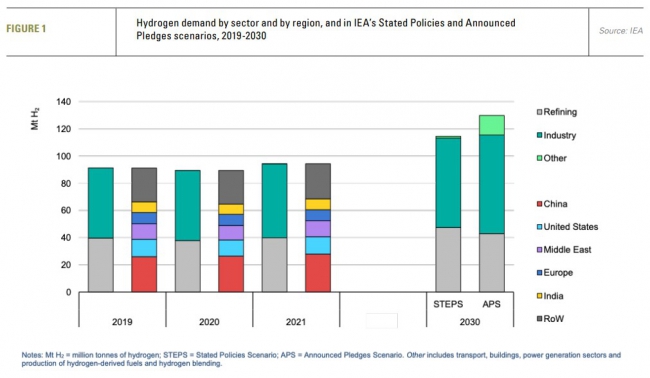

That was the main conclusion from the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2022 Global Hydrogen Review, published in September. By the end of 2021, global annual hydrogen demand increased to 94mn metric tons, up from the pre-pandemic level of 91mn mt in 2019. This is significant, but still limited given the interest production of green hydrogen is attracting globally in the drive to accelerate energy transition. It is equivalent to about 2.5% of global final energy consumption. The IEA estimates that this will grow to 115mn mt by 2030, well below the 200mn mt estimated to be required by 2030 in order to be on track to meet net-zero by 2050.

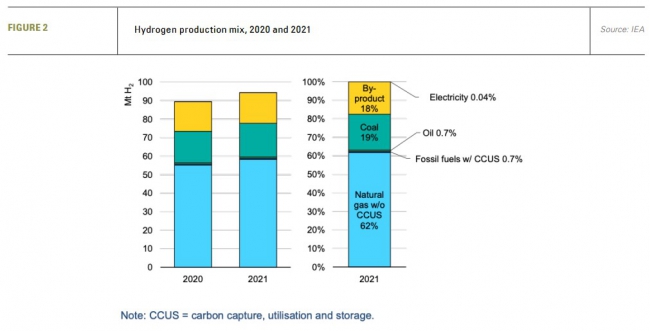

What is disappointing is that out of this, low-emission hydrogen was less than 1mn mt, and, even then, almost all of it came from plants using fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

On the positive side, according to the IEA, the global pipeline of projects for the production of low-emission hydrogen is growing fast, with production of hydrogen from electrolysis expected to reach 9-14mn mt by 2030. But this is still far short of the EU’s requirement to supply the 20mn mt of hydrogen targeted in the Fit-for-55 package and the REPowerEU plan.

On the other hand, there are increasing numbers of major companies entering into strategic partnerships to secure hydrogen for use in hard-to-abate sectors: heavy industry, transport and shipping.

The IEA states that uncertainties about demand, lack of regulatory frameworks and of available infrastructure to deliver hydrogen to end users, is slowing down project implementation. Only about 4% of projects at advanced planning stages are under construction or have reached final investment decision (FID).

Even though it is encouraging to note the strong momentum behind hydrogen, the relatively slow growth so far, particularly of green hydrogen, must be accelerated substantially if the levels needed to achieve decarbonisation targets are to be achieved.

Global hydrogen demand

Global hydrogen demand increased by 5% in 2021 (see figure 1) to 94mn mt, demonstrating recovery from the effects of the pandemic. But most of the increase came from usage in traditional applications, particularly in refining and chemicals.

Demand for hydrogen in new applications, such as in heavy industry, transport, power generation and the buildings sectors or the production of hydrogen-derived fuels, was very low in 2021. China was the world’s largest consumer in 2021, with the US second.

IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), based on current policy settings as well as policies that have already been announced, suggests that hydrogen demand could reach 115mn mt by 2030. Its Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), that assumes that all climate commitments made by governments around the world will be met in full, leads to 130mn mt by 2030. However, based on actual performance and challenges so far the APS outlook is likely to prove optimistic.

Hydrogen production

Most hydrogen production in 2021 was in the form of grey hydrogen, from unabated fossil fuels (see figure 2), with no benefit to climate change. Production of low-carbon hydrogen – using CCS – was very low, less than 1mn mt, and almost all of it was blue hydrogen.

However, many new projects have been announced for the production of low-carbon hydrogen, with the expectation that future growth is likely to be much faster. The IEA estimates that if – against experience so far – all of these are constructed, this may reach 24mn mt by 2030.

Notable among new initiatives is the new US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). This includes major provisions to support production of low-carbon and green hydrogen through “production credits” – by as much as $3/kg of hydrogen when produced using renewables – and is expected to have a major impact over the next ten years.

The US hopes that the IRA production credit will incentivise low-carbon hydrogen producers, maximise its use in heavy industrial processes and create new industries based on replacement of fossil fuels by hydrogen in areas such as shipping, aviation, transport and as a means to store and transport energy.

According to the IEA, electrolyzer manufacturing capacity is about 8 GW/yr, but based on industry announcements this is expected to increase six-fold by 2025 and it could exceed 60 GW/yr by 2030, with costs expected to fall by as much as 70% by then. But the IEA warns that developing these projects will require time and support and, based on current experience, some may never be realised. Even though momentum is building, the IEA has called for greater policy support to get this going faster.

Large amounts of green hydrogen are expected to be produced in Latin America, Middle East and Africa, often for export to Europe and Asia. These can help reduce European industry emissions while at the same time build low-carbon energy sectors in developing countries. But to achieve that goal, the EU must formulate strict economic, environmental and social criteria for imports.

Several electrolyser projects were announced last year in China. The country is the world's largest hydrogen producer and consumer and, through massively increased R&D spending, its goal is to become the world's largest hydrogen technology provider.

Hydrogen infrastructure

The IEA says that today hydrogen is mostly produced close to where it is used. But ultimately, the potential for green hydrogen production will be a function of land availability. As production volumes increase, transport distances will need to expand to meet increasing demand. As a result, “significantly more hydrogen infrastructure will need to be developed to connect areas with good resources for low-carbon hydrogen production with markets.” This is particularly the case for green hydrogen production in North Africa and the Middle East – where land availability is not a problem and renewable potential is vast – to be exported to Europe.

Currently there are about 2600 km of hydrogen pipelines operating in the US and about 2000 km in Europe.

Over the next few years hydrogen is likely to continue being produced in clusters close to where it is used, mainly industrial facilities or refineries. More widespread use of hydrogen later this decade could require retrofitting and repurposing of existing natural gas networks, as well as building new dedicated hydrogen infrastructure.

Even though many of the elements of infrastructure required to produce and transport hydrogen already exist, the IEA says that “the level of growth of low-emission hydrogen demand required to meet climate commitments and goals will require innovation to scale up the supply chain, including some technologies that are still at an early stage of development, particularly for long transportation distances.”

Hydrogen policies

Hydrogen is now seen by many as key in the transition towards clean energy, with an increasing number of new national hydrogen strategies being announced. Some have progressed into implementation and the development of regulations and legislation to support production and use of hydrogen.

Notable among these is the US Inflation Reduction Act that is expected to accelerate hydrogen production in the US, but also spearhead the development of new hydrogen-based or hydrogen-using industries. Many see this as the most important development in the history of green hydrogen so far. It could become a game-changer.

The IEA’s review has identified five areas that are considered to be necessary for hydrogen deployment during the energy transition:

- Establish targets and/or long-term policy signals to create a vision for the role of hydrogen in the overall energy policy framework to provide stakeholders with certainty that there will be a future market place for hydrogen

- Policies to support demand creation for low-emission hydrogen67 as a key lever to stimulate its adoption as a clean energy vector

- Policies to mitigate investment risks in projects across the hydrogen value chain, facilitate access to finance and accelerate deployment

- Promote R&D, innovation, strategic demonstration projects and knowledge-sharing, which are essential to drive down costs and increase the competitiveness of hydrogen technologies

- Establish appropriate regulatory frameworks, standards and certification systems to assure practices, mitigate barriers, facilitate trade and boost investor and consumer confidence in a low-emission hydrogen market.

The review uses these areas to inform policy-makers about progress and implementation gaps. Governments need to move from announcements to actual policy implementations and removal of regulatory barriers.

In Europe, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are launching new policy and subsidy schemes that are expected to accelerate project investment decisions.

Impact of the energy crisis

The IEA concluded earlier in the year that the world is falling short on climate goals and reliable clean energy supplies, stating that “even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the world was far off track from achieving its shared energy and climate goals.” The energy crisis and the war in Ukraine have made this even more challenging.

On the other hand, high natural gas prices mean that blue hydrogen is now that much more expensive to produce, something that may help accelerate production on green hydrogen. High natural gas prices are also leading to calls for acceleration of energy transition and replacement of natural gas by green hydrogen. But these are likely to prove optimistic as the window of opportunity may be short. High gas prices are expected to come down significantly by 2026.

In its World Energy Investment 2022 report, the IEA states that “Clean hydrogen-focused companies are raising more money than ever before, and the value of a portfolio of leading firms in this space has quadrupled since the end of 2019.”

An example is the Hy24 hydrogen fund, backed by global companies and financial institutions including TotalEnergies, Baker Hughes and Axa, that a year after its launch managed to raise €2bn to invest in green hydrogen projects. Another is the IPCEI Hy2Tech project, approved by the European Commission, to support the development of the hydrogen value chain, including generation, fuel cells, storage, transport and distribution of hydrogen and end-user applications, especially in the field of mobility. It is expected to receive €5.4bn of public support from 15 EU member states.

But annual investment in low-carbon hydrogen is still quite low, standing at around $0.5bn. In order to supply the extra 15mn mt of hydrogen targeted in the REPowerEU plan, the IEA estimates that “cumulative capital investment totalling around $600bn globally would be needed up to 2030, with 60% of this for infrastructure outside the EU.”

On a more positive note, looking ahead, the IEA states that the global energy crisis is boosting interest in low-carbon hydrogen and that, with more policy support, the pipeline of projects should accelerate.

Challenges

Clearly hydrogen is unlikely to replace natural gas in substantial volumes any time soon. For example, based on the IEA Review, the EU is unlikely to meet its target of 20mn mt by 2030. As a result, plans to accelerate phasing-out consumption of natural gas on the assumption that it will be replaced by green hydrogen are premature. This must reflect actual growth – or realistic estimates - in the production of green hydrogen. Otherwise, the EU is in danger of sleep-walking into another gas supply crisis in a few years, with the risk of prolonging the use of highly polluting coal and lignite, much as is happening now.

Otherwise, Saudi Aramco CEO Amin Nasser’s warnings that, at a time of growing energy demand globally, “governmental transition plans for alternative fuel and energy sources failed to stand the test of time” and that there is “little hope of ending the crisis soon”, may prove to be prophetic.

It is telling that Fatih Birol, IEA executive director, felt the need to state that “there are growing signs that hydrogen will be an important element of the transition to an affordable, secure and clean energy system, but there are still major advances in technology, regulation and demand needed for it to fulfil its potential." In other words, he admits that as things stand, unlocking hydrogen’s potential will take time – we will not be getting there any time soon.

The negative side of setting up ambitious hydrogen targets and not meeting them is that it may have unwanted consequences. Europe, based on policies for a rapid transition to green energy – in which green hydrogen is expected to make a very significant contribution – is accelerating phasing out natural gas. If green hydrogen targets are not met, as the IEA review shows, we may end-up with another energy crisis as we approach 2030.

The IEA also said a lack of demand-creation could hinder final investment decisions, and called on governments to move from policy announcements to implementation.

Similar warnings have been made by the industry association Hydrogen Council, which pointed out that most of the projects it tracked remained in the announcement phase.

In addition, commercialisation and deployment of green hydrogen on a large-scale faces significant challenges with regards to production, storage, transport and distribution and end-use that need to be addressed in order to bring costs down and improve competitiveness.

Even then, there are warnings that green fuels – ammonia and methanol – costs could be high in 2050, limiting their competitiveness against conventional fuels, even after the projected cost-cutting innovations and scale-up, that merit consideration when developing future plans.

Another challenge is the amount of new renewable energy that would be required to produce green hydrogen – the process is energy-intensive. According to Recharge calculations, producing 14mn mt of green hydrogen annually by 2030 would require 186 GW of offshore wind, or 444 GW of solar power (using capacity factors of 43% and 18%, respectively). By the end of 2021, the world had installed 55.7 GW of offshore wind and 843 GW of solar. Evidently, in order to produce the quantities of green hydrogen needed to achieve net-zero by 2050 – estimated to be about 600mn mt annually – global renewable generation capacity must be expanded massively.

However, there are signs that, at least in Europe, the steel sector may be taking the lead. The IEA said that “hydrogen project announcements are growing fast, just a year after the first pilot plant using hydrogen in the direct reduction of iron started production.”

There is a lot of hope but also hype behind green hydrogen. The IEA’s review shows that hope abounds, but at present hype predominates. Much more needs to happen before green hydrogen delivers on its promise.