[GGP] The Future of Coal

Over past centuries, coal has helped power economic development and lifted billions of people out of poverty. Coal’s role has accelerated since 2000, with global consumption increasing by almost two-thirds, driven by its rising use in China and India. The global coal trade doubled to 1.5 billion tonnes a year over the same period. With a rapidly expanding supply from Australia and Indonesia meeting this demand, as well that of other major importers including Japan and South Korea, the global coal landscape was effectively redrawn.

At the same time, coal was emerging as a leading contributor to climate change and air pollution. To keep within sight of the Paris Agreement target of restricting global warming to ‘well below 2C’, coal burning for power must decline rapidly, leaving the energy systems of advanced economies by 2030, and of developing economies by 2050. However, it is the urgent need to address air pollution and the increasing competitiveness of renewables that are hastening change in countries that depend on coal.

Hopes of an early and rapid decline were raised in 2013, when China’s coal consumption peaked earlier than expected. China is the largest single determinant of coal demand, accounting for almost half of all global coal consumption and one in every four tonnes of traded coal. Global coal demand fell in turn, declining from 2013 to 2016. But with a small increase in demand last year, there are now concerns that coal may cling on, plateauing rather than declining at the pace required.

The future of coal remains an urgent question. Global trends mask different regional stories – while climate and air quality policies, the emergence of shale gas and the collapsing cost of renewables have all added to coal’s decline among many member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and in China, rising demand in parts of Asia have largely offset these falls.

While an international consensus on the need for a fast and orderly coal phase out is forming, exporters of coal and related technologies continue to hold hopes of a future market for coal in these countries. The risk is that despite the disruption that coal is facing in established markets, new coal supply and demand infrastructure continues to be developed, and that once in place, it will lock out cheaper and cleaner energy technologies.

The collapsing economics of coal

Britain, which was the first country to develop coal-fired power, may now be one of the first to end it. Last year saw the UK’s first ‘coal-free’ day since start of the Industrial Revolution. June saw the number of hours powered without coal pass a landmark 1,000 – or a cumulative 42 days – this year. At this rate, British coal plants will be idle long before 2025, the date that ministers have set for phase out.

Similar commitments are now emerging across the OECD. At least 10 coal-burning EU countries have pledged to eliminate coal between now and 2030, led by France which will go coal-free in 2021. The UK and Canada, which has committed to phase out by 2025, sought to harness this momentum with the launch of the Powering Past Coal Alliance at the UN Climate Summit in Bonn last year. At least 28 countries have now joined the alliance, which requires OECD signatories to end coal by 2030, and developing ones by 2050.

Rising carbon prices and the shift towards gas as a low-carbon ‘transition fuel’ are contributing to coal’s decline, but the collapsing cost of renewables is the real game changer.

In the UK, new renewable generation is already cheaper than the cost of new gas per megawatt hour, and costs will continue to drop significantly. And across Europe, a new generation of subsidy-free renewable energy is on the horizon. Coal phase out in countries such as the UK and Austria may be also helped by the fact that ageing coal plant is due for replacement. At the same time, the economics of maintaining coal plants look increasingly dubious. Over half of Europe’s coal-fired power stations are now loss-making, and almost all will be by 2030, according the NGO, Carbon Tracker. Delays in closing this capacity could result in €22 billion in losses across Europe, and €12 billion in Germany alone, to 2030.

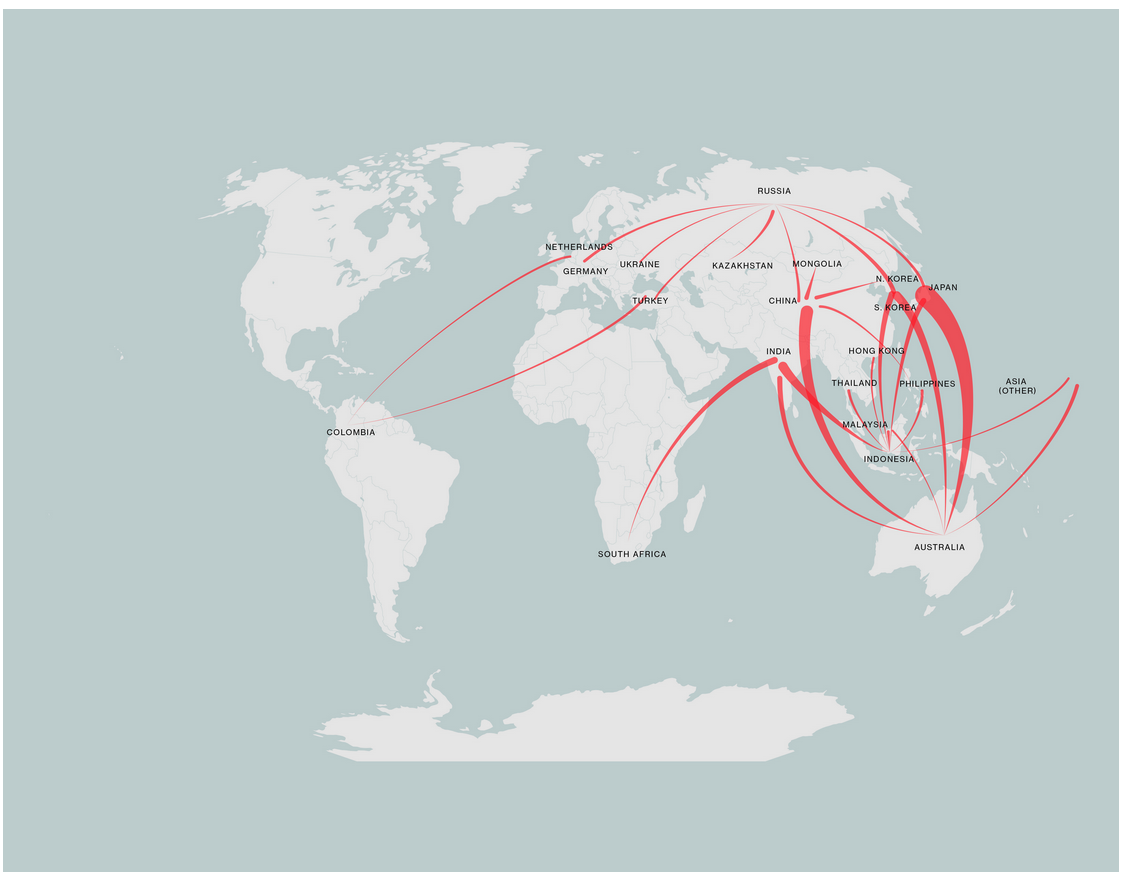

Coal trade flows

The graphic shows global coal trade flows, which have become increasingly focused on Asia as many advanced economies have moved towards gas and renewable energy. Over the past ten years, China and India’s growing demand transformed the trade. Australia and Indonesia emerged as the world’s biggest exporters, accounting for over half of global exports. The data shows all coal trade flows above 10 million tonnes per annum in 2016. Here are the top five:

Australia to Japan 123 Mpta

Indonesia to China 106 Mpta

Indonesia to India 95.7 Mpta

Australia to China 73.6 Mpta

Australia to India 56.2 Mpta

Source: resourcetrade.earth

Managing the political economy of coal decline

It might appear that in this context, commitments to phase out coal will not require huge political will. Yet the vast majority of coal for power is mined and consumed in the same country. Those countries that are committed to coal phase out tend to be importers with little or no domestic production – Canada is the anomaly here.

Managing coal’s decline in countries such as Germany, Poland, the US and China – where domestic coal interests are powerful constituents – is far more complicated.

In the United States, pledges to revive the coal sector have become a political battleground, even though the industry employs only about 50,000 people.

The Trump administration argues that the reversal of Obama-era policies including the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan and support for the Paris Agreement would restore the coal industry and mining jobs. As Trump put it, he ‘was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris’. By contrast, the Mayor of Pittsburg, at the heart of coal country, reaffirmed the city’s commitment to Paris ‘for our people, our economy and our future’.

Despite the rhetoric, there are few signs of a coal boom in the US. Coal’s decline over the past few years is largely explained by its inability to compete with domestic shale gas and renewables at home, and high-volume, low-cost exporters abroad. This would still be no guarantee of jobs, with automation reducing the labour requirements of the mining sector.

These pressures are well understood in China, the world’s largest coal producer, consumer and importer. While the Chinese leadership has not committed to phase out coal, it is proactively phasing down. Damage to public health caused by air pollution are thought to be equivalent to more than 10 per cent of China’s GDP.

Improving air quality and closing down surplus and inefficient coal and heavy industry are strategic priorities under the 13th Five Year Plan, and are crucial to China’s structural transition. Managing the decline of coal mining regions will be tricky, with almost three million coal workers to reskill and many ‘zombie’ companies to wean off of public finance.

Similar dynamics are now emerging in India at an earlier stage of development. Its cities already dominate global air pollution rankings, and civil society campaigns for clean air are gaining pace. Solar and wind power is now being sold at a lower cost than two-thirds of India’s coal power. With coal plants running at around half of their full capacity, there is growing concern that stranded coal assets – those that are losing their value due to the low-carbon transition – may present a risk to India’s banking system.

India’s increasingly ambitious renewable targets and the government’s announcement of a moratorium on new coal plant approvals until 2027 may mark the most significant turning point yet for coal.

Phase down at home, phase up abroad?

Despite this disruption at home, support for coal continues. China, Japan, South Korea and India alone account for an estimated $22 billion of the $24 billion of investment in new coal projects planned by G20 countries, the vast majority of which is in India and middle-income economies in Southeast Asia, according to the NGO, Oil Change International.

Around 500 million tonnes of new coal capacity is currently under consideration, according to the International Energy Agency, justified by expectations of rising demand in these markets.

Policies on coal play an influential role in development choices. While most development banks will finance coal only ‘in exceptional circumstances’, the Asian Development Bank continues to support high-efficiency, low-emissions or ‘clean coal’ technologies, in line with the interests of its major stakeholders.

Coal exports occupy a central role in Australia’s bilateral relationships in the region, and it reportedly lobbied the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to fund coal. In a move likened to ‘selling tobacco at a cancer conference’ the US sought to strike coal deals with developing countries at the last UN Climate Summit.

China’s overseas choices are likely to be among the greatest determinants of future coal demand. The Belt and Road Initiative will entail massive infrastructure development and looser capital controls. It could play a transformative role in helping partner countries develop clean energy systems, especially if the AIIB develops the right policies to deliver its promise of being ‘lean, green and clean’.

However, the Belt and Road could also act as an ‘escape valve’ for squeezed Chinese coal and heavy industrial interests. Populous, energy-poor countries along its route including Pakistan and Bangladesh are already emerging as growth markets for coal.

There is clearly demand for energy in all of these markets, but crucially, this need not mean a future for coal. Coal is no longer the cheapest energy source in many of these markets, and where it is, governments are starting to acknowledge the social and environmental costs of its use.

As India’s recent policy shifts indicate, the societal and economic headwinds coal is facing are not exclusive to rich countries – they are evident further down the development curve. ‘Clean coal’ plus carbon capture and storage could in theory mitigate these impacts, but these technologies are not materializing on the ground at anywhere near the speed required.

There is now a window of opportunity in which to shape the future of coal. From the emergence of ‘coalitions of the willing’ such as the Powering Past Coal Alliance, to India’s leadership of the International Solar Alliance alongside France, momentum around coal phase out is growing quickly, and both demand and support for clean technologies is accelerating.

One key question both for the success of these initiatives and for the future of coal will be the extent to which they are supported or undermined by the policies of the major exporters of coal and coal technologies – notably Australia, Indonesia, China, Japan and South Korea – and of the AIIB, Chinese development banks and other key actors along the Belt and Road.

Siân Bradley

Siân Bradley is a Research Associate, Energy, Environment and Resources at Chatham House. This article first appeared in The World Today, the magazine of Chatham House. www.theworldtoday.org

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.