[GGP] Natural Gas Market Reforms in East Asia: Motivation, Development and Consequences

The year 2017 marked an important turn in national developments in natural gas markets in the Asia Pacific Region: Japan saw its next stages in market liberalization in natural gas, electricity and heating sectors; China, on track in becoming the largest global importer of natural gas, might have crossed the watershed between import parity netback pricing and market pricing; while Korea announced its ambitions to break up monopolies in the natural gas and electricity sectors. In this article, the details of these developments are examined.

The Asia Pacific is the one of the largest natural gas consuming and importing regions in the world. China, Japan and Korea, three of major gas-consuming countries in this region and the world overall, are working on restructuring their natural gas sectors as part of wider energy sector reform agendas focused on overcoming domestic issues.

In Japan, the main problem is the lack of connectivity between the regions and the lack of competition. In China, the cost-plus pricing approach used to create problems for the expansion of domestic gas production and undermined international activities of the Chinese companies because of the gap between lower domestic prices and higher LNG prices, while the role of natural gas in the energy sector overall remained insufficient to help China reach its emission reduction targets. The Republic of Korea tries to reform the natural gas sector led by state corporation. Below we will have a look at the details of these developments and examine whether these changes bear the potential to transform the structure of the regional gas market.

Natural gas market reform in Japan

Japan is one of the largest importers of natural gas and for decades held the spot of the largest buyer of LNG in the global market, with nearly 100% import dependency. Infrastructure and the natural gas transportation system in Japan traditionally belonged to vertically integrated private energy companies. Regional monopolies were allowed to prevent multiple investments. As a result, natural gas transportation systems of different prefectures are not well connected to each other. The problem exists in various sectors, including in natural gas and electricity. This created some serious problems after the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power plant (NPP) in 2011, after which the nuclear sector of the country was put on hold to undergo safety checks. Regions facing electricity shortages could not receive adequate amounts of neither natural gas nor electricity from adjacent provinces. The imports of fossil fuels, including LNG, increased substantially, while this coincided with a period of historically high prices for oil and LNG. As a result, energy market reforms were accelerated. Energy market reforms in Japan aim to overcome the disconnectedness of the networks as well as to promote new business models for energy companies.

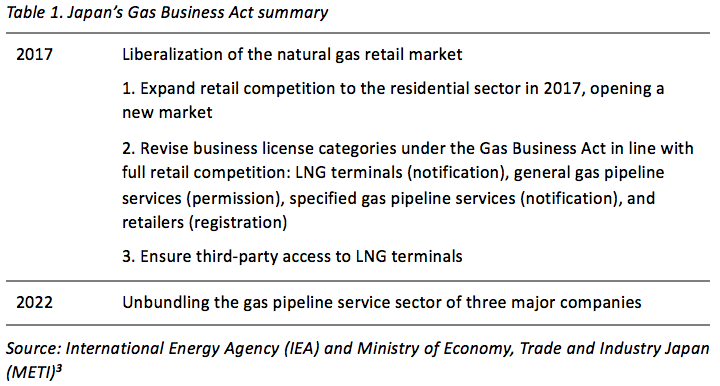

Directions for the natural gas sector development were summarized in the Gas Business Act (see Table 1) and include:

• Ensuring security of supplies;

• Decoupling gas prices from the oil price and ensuring the lowest possible rates;

• Expanding the areas serviced by gas companies through greater diversity of retail choices for gas companies and pricing plans for gas consumers;

• Diversifying the uses for natural gas.

Before this liberalization of the natural gas retail market, it was divided into two sectors: the liberalized sector and regulated sector. Consumers had the right to choose suppliers if their consumption exceeded 100 000 cubic meters per year. If annual consumption was less than 100 000 cubic meters per year, the regulated tariff was applied (see Table 2). With the implementation of the Gas Business Act, the regulated sector now became fully competitive.

.png)

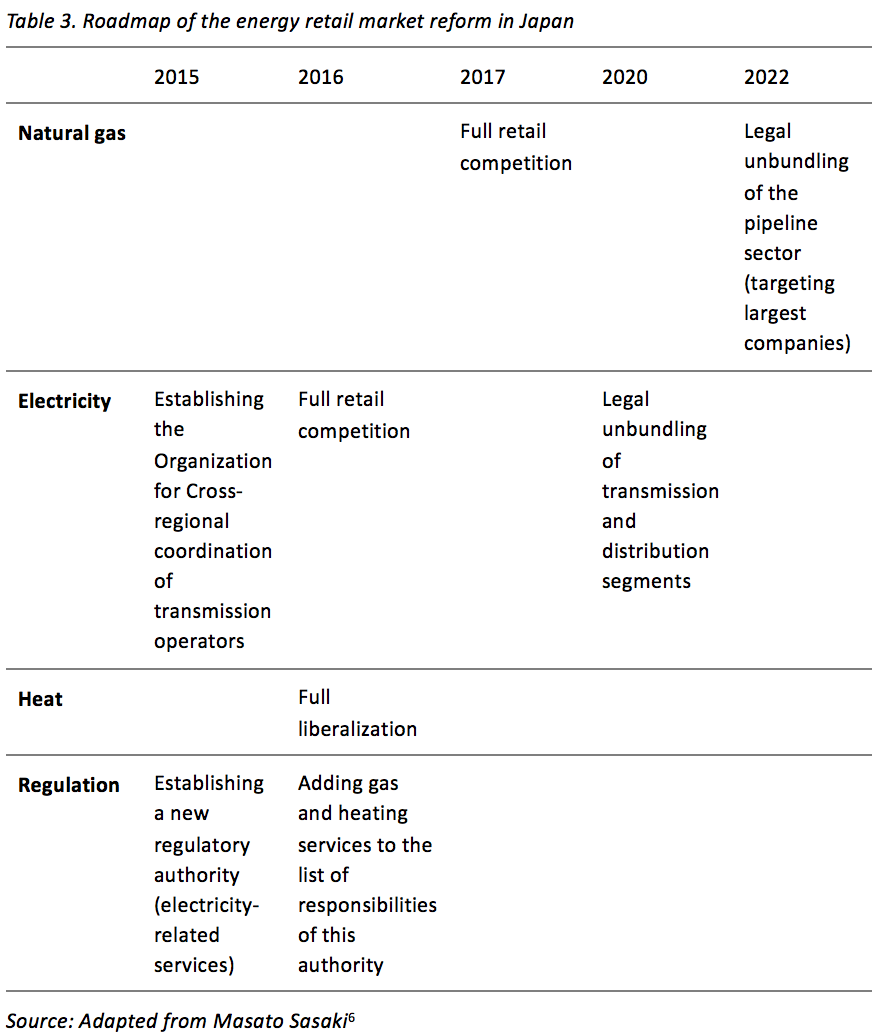

The reforms in the natural gas sector are part of an overall energy sector liberalization effort. The developments across natural gas, electricity, heat sectors and in the field of regulatory oversight are all part of a wider energy retail market reform Roadmap (see Table 3).

In our view, these significant changes in the energy sector in Japan may have serious regional implications. One particular reason is that liberalization of the gas market also concerns the LNG sector. Besides access to the pipeline infrastructure, the government plans to facilitate access to LNG import terminals and other LNG infrastructure as well. Companies only need to officially notify the regulator at the beginning of their activities and receive permission. Apart from existing gas utility companies, New business entities (mainly electricity generating companies) have been registered as gas retailers and have started launching their gas retail business. In 2022, the pipeline sectors are to be legally unbundled from their manufacturing or retail gas business sectors.

What this means for the regional and global LNG market is that more Japanese companies will refer to the spot market in order to meet their obligations in the domestic market as they gain access to both infrastructure and customers. This explains the overall interest of Japanese companies towards more flexible conditions for natural gas procurement (including less rigid terms of long-term contracts as well as a fully functioning regional gas trading hub for spot deals and hedging operations). But this reform does not yet provide sufficient basis for creating such natural gas trading hub in Japan.

Natural gas market reform in China

China is one of the most prominent players in the natural gas market: not only did it overtake South Korea as the second largest importer of LNG in 2017, but it is also actively expanding its pipeline imports and in the context of dropping LNG imports in Japan as a result of re-start of nuclear power plants, China may well become the largest gas importer in the world in 2018. Due to the nature of China’s gas import strategy (a ‘compass’ of gas import routes connects the country with Central Asia, Southeast Asia, world LNG markets and potentially Russia) and its sheer size, developments in this market carry the potential of China taking on an integrator’s role in the Asian natural gas market.

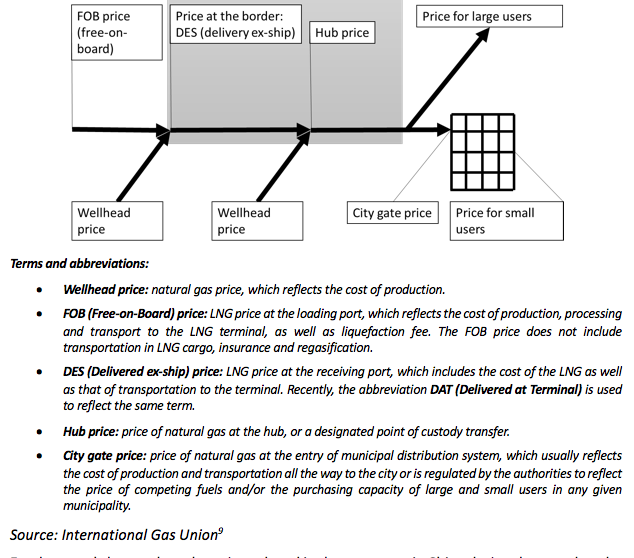

As of 2018, China’s natural gas market looks closest to actually realizing a natural gas trading hub, but the situation in the natural has market of this country was certainly not like this before. Until 2011, the market was largely regulated, with the government setting the levels of wellhead prices as well as the prices for end users (for clarification of various types of prices, see Figure 1). This system was not productive: gas companies would experience significant difficulties because of the gap between international LNG prices and domestic prices. A low level of domestic prices also inhibited natural gas exploration and production efforts domestically. Overall, the regulated gas pricing system created obstacles to the expansion of natural gas within China’s energy mix, which has become imperative ever since the PRC took a path toward cutting emission levels.

Figure 1. Types of natural gas prices along the supply chain

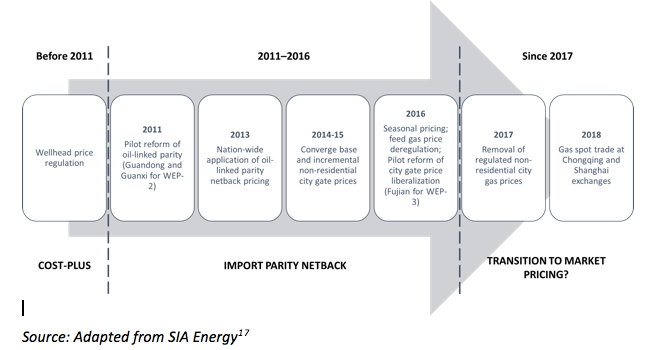

Fundamental changes have been introduced in the gas sector in China during the past decade. Since 2011, China makes consistent steps to move away from price regulation (or cost-plus principle) toward market-based pricing.

In December 2011, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) introduced pilot netback pricing in the Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. Maximum gas prices at the city gate in these provinces became linked to the mazut and LPG price imported in Shanghai by a ratio of 60:40 with a discount of 10% whilst the weighed purchasing capability of citizens in each region and transmission tariffs was also taken into account.

The next step was undertaken in July 2013, when the NDRC announced a two-tiered city-gate price system for 29 provinces. The price controls for all types of gas supplied by pipeline switched from the wellhead to the city gate. Prices for offshore, domestic and imported LNG and unconventional resources became exempt from price controls unless delivered via regional pipeline networks. CNOOC received exclusive rights to buy offshore gas from independent producers. Prices in the municipalities were defined by a base demand and the price of incremental gas volumes. Natural gas consumption exceeding the 2012 level was classified as the ‘incremental volume’. The price of natural gas consumption beyond the ’base demand’ was indexed to the import price of mazut and LPG in Shanghai at a ratio of 60:40 with a discount of 15%. The price in each region was weighed by the transportation costs from Shanghai and the purchasing power in each region.

Therefore, in each region, the price ceiling and the base demand price were at a different level.

In 2015, the NDRC announced that China officially ended its two-tier gas pricing system. The ‘incremental’ city-gate prices were cut and the factual city-gate prices were raised in every province in order for the two different gas prices to converge. In 2017, the NDRC announced a new stage in its natural gas market reform: regulation of non-residential city gate price is now to be removed. Gas companies are encouraged to gradually split sales and pipeline businesses to promote a market-based pricing mechanism and the government is only to step in when abnormal price fluctuations occur. Finally, at the end of 2017, it was announced that the creation of a Chinese gas index is one of the priorities, and there are two exchanges now trading natural gas: Shanghai and Chongqing. These developments suggest that the Chinese natural gas market moves toward a principally new stage in its development. As summarized below (Figure 2), the movement is logically geared towards the market pricing of natural gas.

Figure 2. Natural gas pricing reform in China: Chronology

What will be the outcomes for the regional and global gas markets? Firstly, it is important to mention that China has created a set of pre-conditions for competitive price discovery (removal of regulated prices). Secondly, China is currently making steps to launch a gas price index. If such an index earns the trust of outside players, it may serve as the regional index as well. Therefore, changes in the national gas market of China can have a transformative influence on the regional gas market structure.

Energy market and state energy company reform in South Korea

Together with Japan and China, South Korea is one of the largest players in the LNG market, and until 2017 it was the second largest importer of LNG after Japan, until overtaken by China. Currently, the natural gas market in Korea is also experiencing some changes.

Wholesale gas market in Korea is monopolized by the state company, Korea Gas Corporation (KOGAS). Traditionally KOGAS was the sole seller of natural gas in the wholesale market and in addition to that, it has always been the largest importer of LNG in the country, being responsible for over 90% of all LNG imports. In June 2016, the Korean government approved the plan of gradual opening of gas imports and the wholesale market to the private sector by 2025, , after KOGAS’ 9 million tons per year long-term contracted volumes of LNG with Qatar and Oman expire in 2024. The liberalization of the gas market is aimed at strengthening competition in the gas and electricity market.

It is worth mentioning that natural gas and electricity sectors are closely interlinked in Korea, like in many other countries: the developments in the electricity generation mix directly affect demand for natural gas. Under the 8th electricity plan announced in 2017, which reflects environmental and safety factors in addition to objectives of stable power supply and economic efficiency, Korea will produce more power from renewable energy sources and natural gas, while gradually reducing its reliance on nuclear power and coal. Thus, the role of natural gas is likely is likely to strengthen. Like in natural gas, electricity sector is also dominated by a single entity – Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO). While KEPCO and other companies in the electricity and industrial sector could import LNG, it was possible to use it for their own consumption only. However, as private companies can gain access to the wholesale market after 2025, the competition in gas and electricity markets is very likely to increase.

In January 2019, the new edition of the “National Energy Master Plan” (which is updated every five years) will be published. The National Energy Master Plan is a comprehensive document that covers all energy sectors, and systematically links and coordinates energy-related plans from a macro perspective. The expectation of a new focus in energy policy comes from the fact that the newly elected administration puts more emphasis on the promotion of clean energy sources such as renewables. The administration also stresses the need to decrease consumption of coal and increase the role of natural gas. Gradual retirement of nuclear plants is another factor in the policy change; permissions for new generating capacity are not being granted, while the existing licenses are not being renewed. Overall, it is expected that ‘green energy’ will be the beneficiary of the new energy policy in Korea and in line with that, it is expected that natural gas will be used as a cleaner (‘bridging’) fuel on the road to the renewables era. This potential change in the reforms can put the liberalization of natural gas and electricity markets and role of KOGAS and KEPCO at the center of the reform. In these circumstances, pricing starts to play a major role as it determines the competitiveness of gas in the energy mix versus the alternatives.

Currently, wholesale natural gas price is indexed to raw material cost (LNG import cost and exchange rate) and the retail prices for both natural gas and electricity are regulated. There are no plans yet to change the pricing system. Therefore, liberalization of the natural gas and electricity markets in Korea will remain at a relatively low level for a longer time due to the lack of retail and wholesale market competition and absence of unbundling in the midstream sector. The situation looks similar to that of Japan, with only one difference: in Korea, the role of the monopolist players is stronger, which makes market liberalization something more of a long-term, and quite distant perspective. At the same time, it is important to mention that Korean companies cooperate with the newly founded Japan’s Energy for a New Era’s (JERA) – an innovative energy company with a focus on LNG and trade-liberalization – aspirations toward more flexible conditions for natural gas trade.

CONCLUSION

Three of major gas-consuming countries in Asia and the world, are working on restructuring their natural gas sectors as part of wider energy sector reform agendas focused on overcoming domestic issues. Energy market reforms in these countries are not identical due to different market situation and developments.

• The reforms in the natural gas sector in Japan are part of an overall energy sector liberalization effort. The developments across natural gas, electricity, heat sectors and in the field of regulatory oversight are all part of a wider energy retail market reform Roadmap. More Japanese companies will refer to the spot market in order to meet their obligations in the domestic market as they gain access to both infrastructure and customers. The overall interest of Japanese companies towards more flexible conditions for natural gas procurement is increasing, including less rigid terms of long-term contracts as well as a fully functioning regional gas trading hub for spot deals and hedging operations.

• In China, the cost-plus pricing approach used to create problems for the expansion of domestic gas production and undermined international activities of the Chinese companies because of the gap between lower domestic prices and higher LNG prices. The role of natural gas in the energy sector overall remained insufficient to help China reach its emission reduction targets. The outcomes for the regional and global gas markets is that China has created a set of pre-conditions for competitive price discovery by removing regulated prices. Secondly, China is currently making steps to launch a gas price index. If such an index earns the trust of outside players, it may serve as the regional index as well. Therefore, changes in the national gas market of China can have a transformative influence on the regional gas market structure.

• The Republic of Korea tries to reform the natural gas sector led by the state corporations. Korea announced its ambitions to break up monopolies in the natural gas and electricity sectors. Under the 8th electricity plan, Korea will produce more power from renewable energy sources and natural gas, while gradually reducing its reliance on nuclear power and coal. Therefore, the role of natural gas is likely to strengthen. Private companies can gain access to the wholesale market after 2025, the competition in gas and electricity markets is expected to increase. Liberalization of the natural gas and electricity markets in Korea will remain at a relatively low level for a longer time due to the lack of retail and wholesale market competition and absence of unbundling in the midstream sector.

Thus we may conclude that the three Northeast Asian countries have transformed their domestic natural gas markets in order to have more competition. Their national efforts may well have a spillover effect on the regional market. It is important for LNG buyers to move away from oil indexation toward a pricing principle that would reflect market conditions in the natural gas market (instead of the oil market). This naturally creates the demand for the launch of a regional natural gas trading hub, which becomes a much more realistic outlook in the context of national liberalization.

Possibility of launching a regional gas hub is the topic to be addressed in our next article.

Jinsok Sung, PhD candidate at Gubkin Russian State University of Oil and Gas and researcher at Working Group “Small Scale LNG” at the Energy Center of Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO. Jinsok’s doctoral dissertation is titled “Development of LNG market and comparative analysis of two natural gas pricing mechanisms in the North East Asia”. His research focuses on energy markets, especially natural gas/LNG markets. Address for correspondence: jinsok.sung@gmail.com, jinsok.sung@gubkin.ru

Irina Mironova, Editor-in-Chief of the ENERPO Journal and other publications of the ENERPO Research Center. She is pursuing her PhD in Energy Economics. Irina has previously worked in research at the Energy Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Russian Center for Policy Studies, Energy Charter Secretariat, Clingendael International Energy Programme. Teaching experience includes ENERPO (Energy Politics in Eurasia MA Programme at the European University at Saint Petersburg), Venice International University, OSCE Academy in Bishkek, Saint Petersburg State University of Economics. Address for correspondence: imironova@eu.spb.ru

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.