[GGP] China's Belt and Road Initiative and the Mediterranean Region: The Energy Dimension

Introduction

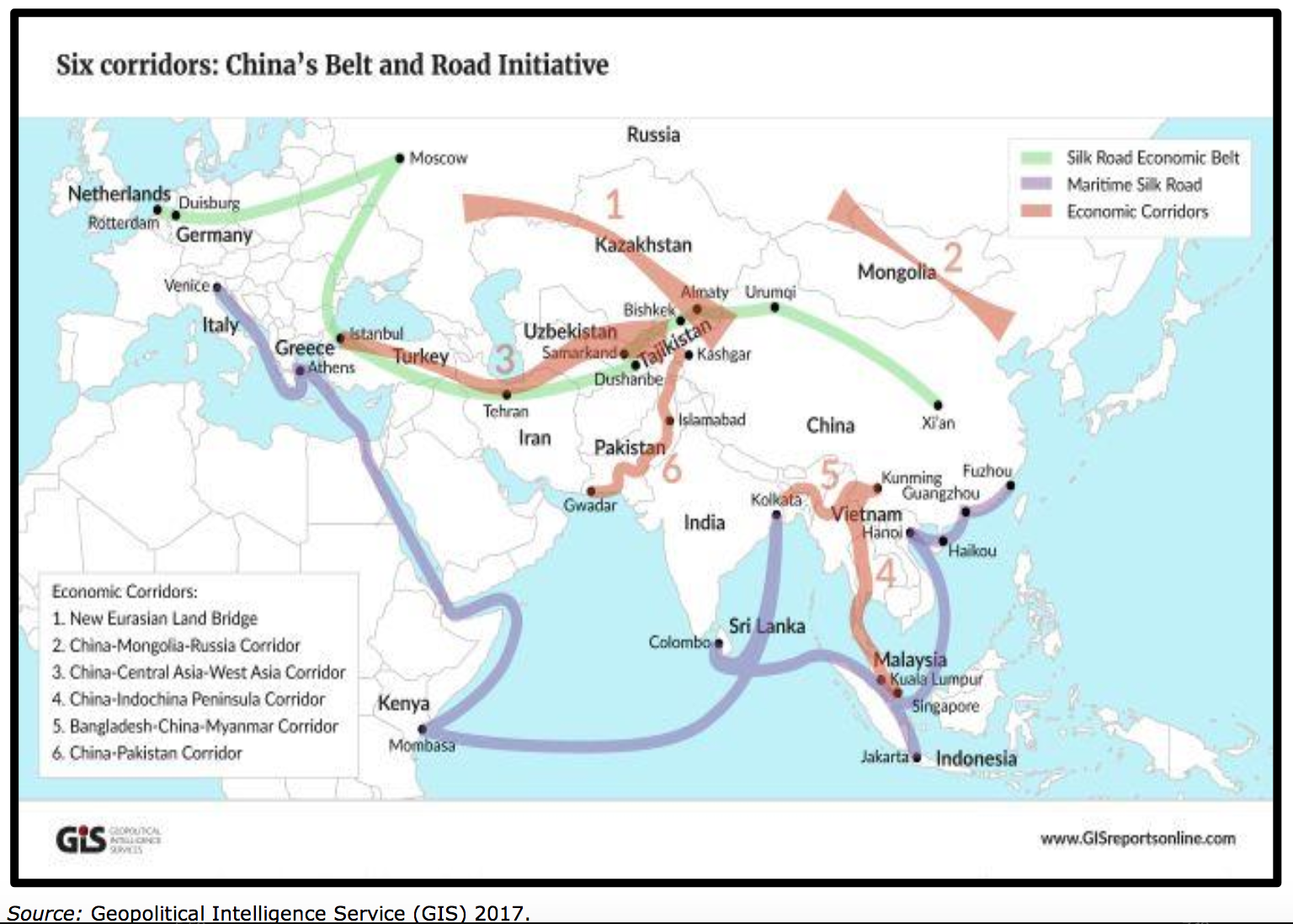

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – previously called ‘One Belt, One Road (OBOR)’ - has been designed by China as its new guiding economic and foreign policy framework with a focus on its direct neighborhood at its southern and western borders, but also reaching out to the Persian Gulf, Africa and Europe, involving 65 countries and 15 Chinese provinces until 2015/16. Meanwhile, investments as part of the BRI have extended to more than 80 countries. As centuries ago during the times of Marco Polo, China views itself as the ‘Middle Kingdom’ geographically and geopolitically and, therewith, as the global center of world trade.

But the BRI is not just a strategy to enhance China’s commercial, trade and other economic interests. According to official declarations by China’s president Xi Jinping in May 2017, designating it as ‘the project of the century’, it is considered as a vehicle to open markets, expand export overcapacities, generate employment, reduce regional inequalities, promote political stability and security through development as well as prosperity and to restore Chinese spheres of influence in the Eurasian landmass and beyond. It is conceived in China’s historical roots, designed as a multipurpose umbrella for its comprehensive economic, domestic and foreign policy development in order to increase its geo-economic and geopolitical influence. Ultimately, it is a renewed form of China’s traditional hegemony over its neighbors and rivals as practiced centuries ago, but adopted for the 21st century.

The BRI has originally been launched by China’s new President Xi Jinping as the OBOR initiative in a speech at the Nazarbayev University in Astana (Kazakhstan) in September 2013. The framework concept, which combines the previous programs of ‘China’s Silk Road Economic Belt’ and ‘21st - Century Maritime Silk Road Strategy (MSR)’, makes the country’s regional neighborhood –both on the continent and in the seas –the main strategic priority in its economic, foreign and security policies along six economic corridors (see figure 1). Should China successfully implement its BRI and its ideas of regional as well as global order, the Eurasian map might be re-defined and the geopolitical influence of the U.S., the EU as well as Russia might be marginalized. But as big as China’s geopolitical ambitions are, the economically related security challenges of the BRI are equally as big. This also holds true for its MSR - strategy, which itself is being considered one of the largest trading networks in world history.

With the BRI, China envisages to spur regional cooperation by leveraging China’s economic and financial power potential of up to USD 1 trillion for regional investments and trade. It will not only link China’s economy with those of Southeast, South and Central Asia, but also with the Middle East (i.e. the Gulf region), Africa and Europe. Already now, China is the world’s largest economy (based on GDP and the World Bank’s purchasing power parity calculations) as well as the worldwide biggest energy producer, exporter, and consumer. By 2020, China could become the world’s largest overseas investor as well. Its offshore assets might triple from USD 6.4 trillion to almost USD 20 trillion.

Figure 1: The Six Economic Corridors of the BRI

China’s geo-economic strategy of an interconnected economy with its neighboring countries and countries beyond the regional neighborhood aims at creating an integrated economic network of supply and value chains - especially in the production, transport and energy sectors. It demands massive investments in ports, airports, transnational railways, highways, container trade and fiber optic cables as well as energy projects such as the development of onshore and offshore oil and gas fields, energy infrastructures and the expansion of renewable energy sources (RES).

Traditionally, China has always interpreted energy import dependencies as vulnerabilities and, therefore, has opted for ‘energy independence’ and self-sufficiency. On the side of its BRI partners, China’s overseas energy projects as part of the BRI need to be analysed in more detail as they offer both opportunities and strategic risks for international energy cooperation and global climate mitigation policies. The overseas (energy) investments in the framework of BRI are becoming ever more important in the light of the mid-and longer-term strategic developments of China’s energy security nexus.

The focus of the following analysis is directed towards the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, here

separately examined for the Persian Gulf region and in a second step North Africa. As highlighted during a conference on “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: The Return of the Silk Road to the Mediterranean” by the KAS Regional Program Political Dialogue South Mediterranean in April 2018, North African countries are looking with great interest and expectations at any larger Chinese investments in their region as part of the BRI. The discussions revealed, however, that they tend to overlook some of China’s problematic conditions and circumstances of those BRI investments as has already been demonstrated in Africa, Central Asia, South Asia and Europe. In the EU, China’s investment policies, including those of the BRI, have come increasingly under criticism as those investments are seen at best to serve the member states’ short-term economic interests, but to undermine their mid-and longer-term strategic interests, such as the EU’s common foreign and security policies towards China and other third powers.

In Germany, China’s largest trade partner in Europe, the China debate has shifted from a largely positive tone to a very critical and sceptical tone. Moreover, and despite the official support of the IMF, its managing director Christine Lagarde recently warned Chinese policymakers of financing unneeded and unsustainable projects in countries with heavy debt burdens, which limits other spending such as debt services and creating balance of payments and makes these countries dependent on China’s geopolitical interests.

According to a report by the Washington Center for Global Development, eight countries included in the BRI strategy are already facing problems of servicing debt due to their large borrowing from China, namely Pakistan, Djibouti, the Maldives, Laos, Montenegro, Mongolia, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

The following analysis will at first give an overview of China’s energy security nexus as well as energy dimensions of the BRI as determining Beijing’s BRI investment strategies. It will then explore China’s BRI strategy focusing on the Persian Gulf as part of its larger energy investment and energy security strategy towards the MENA region. Thereupon, it will give an overlook of North Africa’s energy sector and potential investment options for China’s extending BRI strategy

Read the Full Analysis, China's Belt and Road Initiative and the Mediterranean Region: The Energy Dimension, by Dr. Frank Umbach, Konrad-Adenauer Foundation (KAS), Regional Program Political Dialogue South Mediterranean. HERE

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.