Geopolitics of the energy transition [NGW Magazine]

The International Renewable Agency (Irena) issued a report in January 2019, A New World: Geopolitics of Energy Transformation (GET).

What prompted the report was awareness that “that the growing deployment of renewables has set in motion a global energy transformation with significant implications for geopolitics,” said Irena’s director-general, Adnan Amin.

GET was the outcome of work carried out by an independent commission chaired by former Icelandic president Olafur Ragnar Grimsson and comprising leaders from the world of politics, energy, economics, trade, environment and development.

Introducing the report, Amin said: “The energy sources powering our societies have been undergoing a period of rapid change. Renewables have emerged as a technologically feasible, economically attractive and sustainable choice that increasingly can meet the energy needs of many countries, corporations and citizens. As tackling climate change becomes more and more critical and renewables steadily increase their capacity to meet our energy needs, the global transition to sustainable sources of energy will continue to accelerate.”

He added: “Renewables enable countries to strengthen their energy security and achieve greater energy independence…. The rapid development of renewable technologies and their widespread deployment is certain to have significant long-term effects on geopolitical dynamics.”.png)

There is increasing conviction that energy transformation is changing the world, presenting both opportunities and challenges – creating ‘A New World’ as GET s title says. Adoption of renewables is now based much more on costs and benefits, rather than just environmental factors, and they are becoming as competitive as conventional sources of energy. This has been driven by technological and systems innovation, but political and administrative innovation will also be required.

Innovation is changing the business of energy. Things are getting lighter, cheaper, and easier to build. Digitalisation and electrification are having a profound impact on global energy systems. These trends are not going to stop.

The CEO of Italian power generator Enel, Francesco Starace, said that: “Renewable energy was once referred to as alternative energy, and this hindered the development. Renewables were seen as unpredictable and too expensive. These perceptions prevented the diffusion of renewable energy all over the world. As of today, renewables speak for themselves. They are no longer referred to as alternative energy and they are competitive on cost, they are reliable and they are a mainstream source of energy. This is widely recognised thanks to the efforts of Irena in what has been a decade of change.”

The publication of the report coincides with calls by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) for greater action to avoid the worst effects of climate change. But it will not be plain sailing. Renewable energy is now firmly part of the global energy equation, but there is a very long way to go before it can provide reliably and sustainably the quantities of energy the world needs.

Even Irena warns that renewable energy needs to be scaled up at least six times faster for the world to start to meet the goals set out in the Paris Agreement.

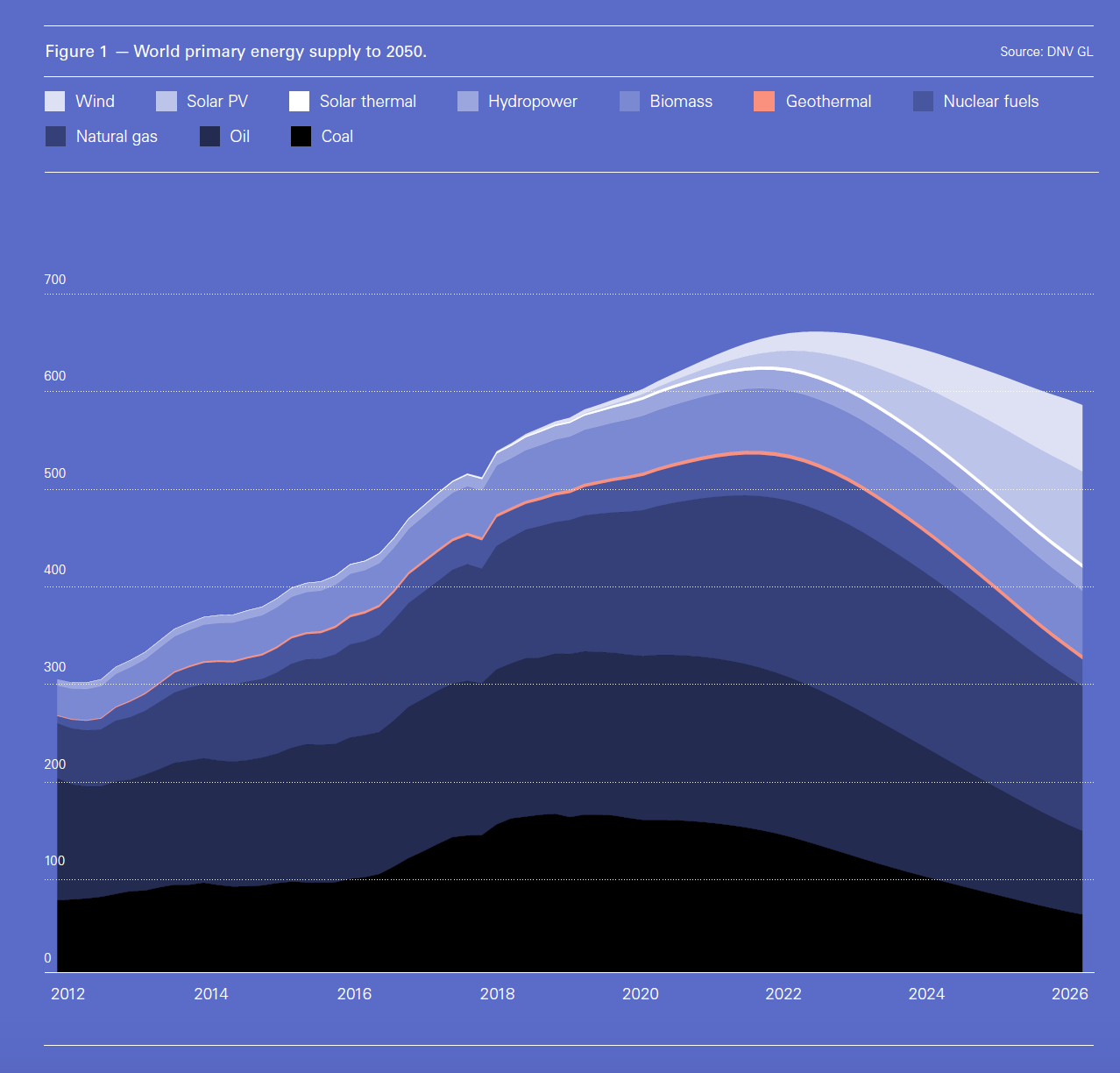

This is illustrated by DNV GL’s ‘Energy Transition Outlook’ to 2050 (Figure 1), largely based on Paris Agreement NDCs.

As DNV GL shows, even by 2040 close to 60% of world primary energy will still be provided by fossil fuels. It will be after 2050 before clean energy, including nuclear, could be providing more than half of world primary energy. And even by then renewables, solar and wind, will be providing only 27% of this.

BP and the International Energy Agency (IEA) are more pessimistic in terms of renewables in their outlooks, showing that fossil fuels will still be providing 74% of world primary energy by 2040.

As can be seen from Figure 1, renewables do not start having any significant impact in replacing fossil fuels until after 2030. Until then, or according to BP and IEA probably until 2040, the world will have to rely mostly on fossil fuels to provide the bulk of the expected growth in primary energy demand. Renewable energy will grow fast and be disruptive, but it can only cover some of the need for energy.

Clearly, energy transition will be a lengthy process, with renewables having a bigger role to play, but they will have to co-exist with fossil fuels for a long time to come. Making sure that the world has ample and reliable access to energy to satisfy demand over this period may complicate the geopolitics of energy transition.

Global energy transformation

Grimsson says in his introduction that “the global energy transformation is already becoming a major geopolitical force: changing the power structures of regions and states, bringing the promise of energy independence to nations and communities, enhancing energy security and democratic empowerment.”

GET concludes that global energy transformation driven by renewables will reshape relations between states and lead to fundamental structural changes in economies and society. The world that will emerge from the renewable energy transition will be very different from the one that was built on a foundation of fossil fuels.

Global geopolitics will change and the dynamics of relationships between and within states will also be transformed. Power will become more decentralised. The influence of states that invest heavily in renewable technologies and build up their capacity to take advantage of the opportunities they create will grow – both economically and geopolitically. A prime example of this is China.

But there are also warnings. The world must avoid the technology dominance of a few. Otherwise, the mistakes of the past may be repeated and the expectation that democratisation and independence will be enhanced may be limited.

In a recent review, German think-tank Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) drew similar conclusions. It said that “the geographical concentration of technology leadership and an imbalance in global finance raise new threats. These may translate into veritable geopolitical risks that require global co-operation in order to be overcome.” It also noted that “the energy transformation process itself is still progressing far too slowly.”

GET also warns that states that rely heavily on fossil fuel exports and do not adapt to the energy transition will face risks and lose influence.

The supply of energy will no longer be under the control of a small number of states, since the majority of countries will have the potential to produce their own renewable energy and achieve energy independence, enhancing their development and security as a result.

Energy transition will generate considerable benefits and opportunities. It is expected to:

- strengthen the energy security and energy independence of most countries;

- promote prosperity and job creation;

- improve food and water security; and

- enhance sustainability and equity.

Some states will be able to leapfrog technologies based on fossil fuels and rely on renewables to provide their future energy. The result of such developments is that the number of energy-related conflicts is likely to fall.

GET recommends that countries must prepare for the changes ahead and develop strategies to enhance the prospects of a smooth transition as the energy transformation will generate new challenges.

Fossil fuel-exporting countries may face instability if they do not reinvent themselves for a new energy age. A rapid shift away from fossil fuels could create a financial shock with significant consequences for their economies. Workers and communities who depend on fossil fuels may be hit adversely.

Risks may also emerge with regard to cyber-security and new dependencies on certain minerals.

Despite difficulties, energy transformation will ultimately move the world in the right direction by addressing climate change, combating pollution, and promoting prosperity and sustainable development.

The report states that as the world gets ready for the geopolitical consequences of energy transformation, it can provide government leaders, business and all sectors of society with a foundation for dialogue and debate, thereby contributing to policy development and new courses of action.

Altogether, a comprehensive set of recommendations backed up by data. But what the timing of these developments is hard to pin down: some are already happening while others will take longer.

Renewable energy growth

Renewables are growing at an unprecedented rate and are consistently surpassing expectations in the power sector. But their contribution to transport, heating and industry is still limited. Nevertheless, the global energy transition is with us, it is irreversible and it is led by renewables combined with energy efficiency.

The impact of this growth has, so far, been mostly in the electricity sector. Electricity accounts for 19% of total final energy consumption - with renewables providing about a quarter of it - but its share is expected to grow as increased electrification of end-use sectors takes place. This is also the view of the IEA in its World Energy Outlook 2018 (WEO2018).

One of the key take-aways from WEO2018 is that of all the forms of energy, electricity will see the most dramatic transformation. In advanced economies, electricity demand growth will be modest, but the investment requirement is still huge as the generation mix changes in favour of renewables and infrastructure is upgraded. In developing economies, electricity demand is expected to be doubled, putting cleaner, universally available and affordable electricity at the centre of strategies for economic development and emissions reduction.

According to WEO2018, renewables have become the technology of choice in electricity, making up almost two thirds of global capacity additions to 2040, driven by falling costs and supportive government policies. This is transforming the global power mix, with the share of renewables in generation expected to rise to over 40% by 2040, from 25% today. Between now and 2040, nearly 90% of electricity demand growth will be in developing countries, with China and India at the forefront.

Electricity networks may in time become the main conduits for cross-border energy transfers, rather than oil and gas pipelines, tankers and LNG carriers. In addition, off-grid renewable energy solutions, including stand-alone systems and mini-grids, have emerged as a mainstream, cost-competitive option to expand access to electricity.

But despite these positive developments and progress to date, the speed of energy transformation is uncertain. Even Irena agrees that the energy transition needs to significantly pick up the pace.

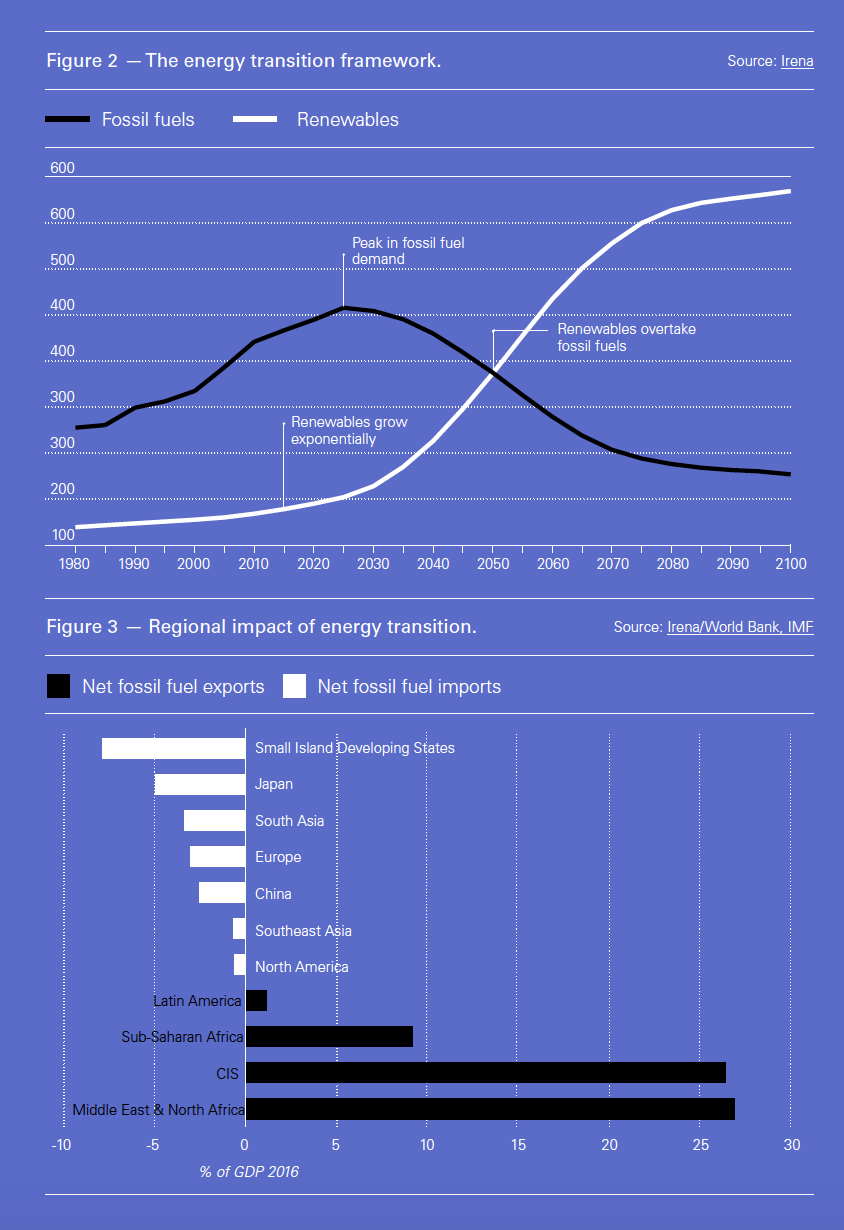

Projections, based on models with differing assumptions, become more uncertain the further ahead they look. Nevertheless they help illustrate the potential dynamics of change, as shown in Figure 2, based on Shell’s Sky scenario.

Achieving the goals set out in the Paris Agreement requires fossil fuel demand to peak, in this case at around 2030, with renewables eventually overtaking fossil fuels, in this case around 2050. In reality, the speed and timing depends on how the dynamic forces of change drive global energy transformation and deployment of renewables. These include:

- declining cost

- pollution and climate change

- renewable energy targets – policy-driven

- technological innovation

- corporate and investor action; and

- public opinion/divestment/litigation

Electricity is becoming the fuel of modern life. In many parts of the world electrical power and political power are inextricably intertwined – keeping the lights on is considered to be a natural right. This has profound implications.

To take an optimistic view, rapid cost declines and a more helpful political and economic environment will drive the shift from an era of centralised power and ownership to one of decentralisation and democratisation.

Impact on geopolitics

As a former US president Jimmy Carter said, “No one can ever embargo the sun or interrupt its delivery to us.” And according to Grimsson, GET represents a first attempt anywhere in the world, from either political, business or academic community, to outline the implications of the new geopolitical structures.

Renewables will transform geopolitics because:

- renewable energy resources are available in one form or another in most countries, unlike fossil fuels that are concentrated in specific geographic locations;

- renewable energy is inexhaustible and more difficult to disrupt;

- renewable energy sources can be deployed at almost any scale and lend themselves better to decentralised forms of energy production and consumption; and

- they have zero marginal costs.

The energy transition will affect different regions of the world regions in different ways. This can be illustrated by looking at each region’s net fossil fuel exports and imports as a share of GDP (Figure 3).

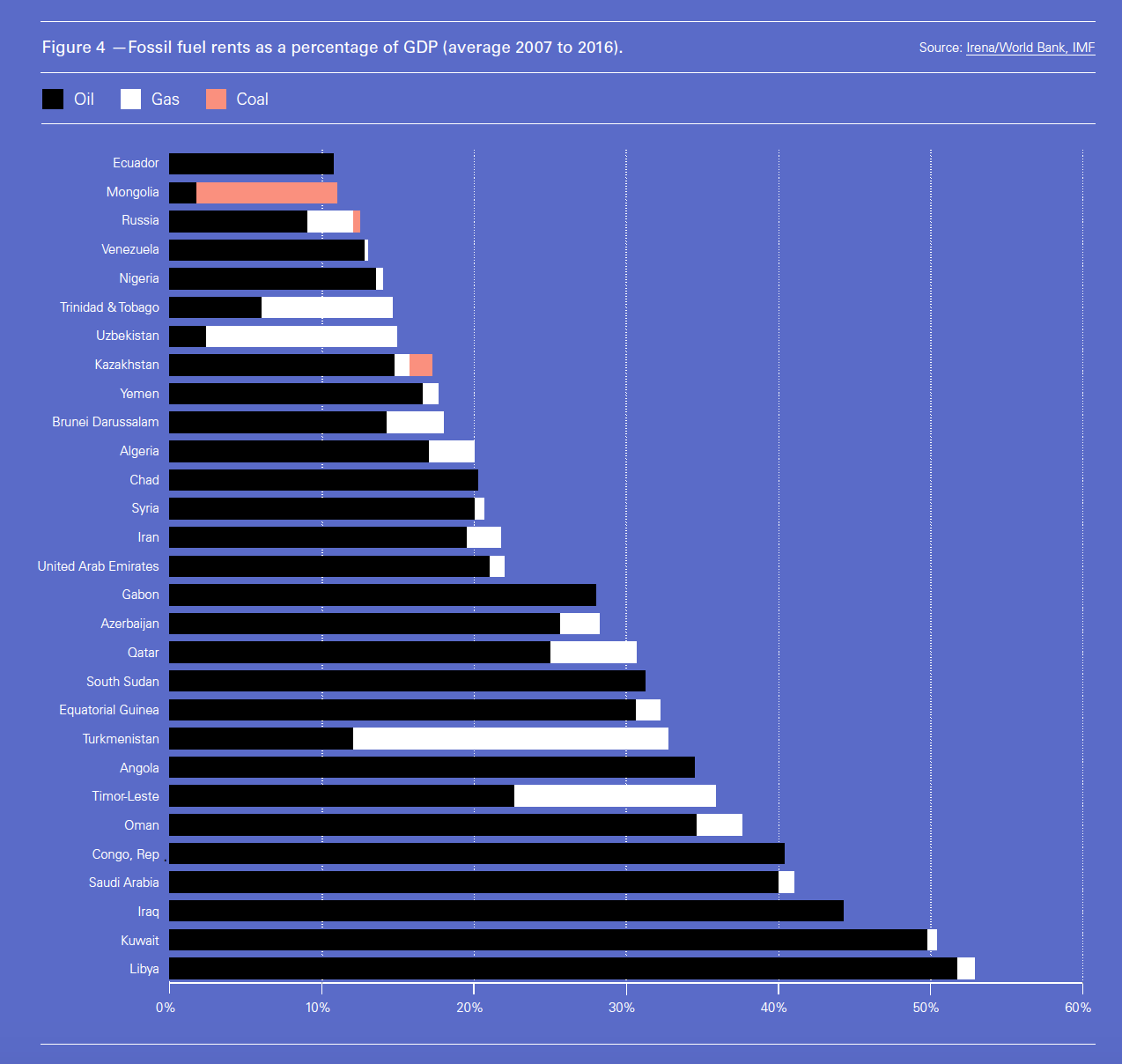

The Middle East and North Africa, together with sub-Saharan Africa and countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS, principally Russia but also Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and one or two other energy producers from the former Soviet Union), are the regions most exposed to reductions in fossil fuel revenues (Figure 4) and diminishing political influence. Declining export revenues will affect their economic growth prospects and national budgets adversely. To prevent economic disruption, they will need to adapt their economies and reduce their dependence on fossil fuels, or risk face instability.

Other regions will benefit if they adopt renewable energy sources rather than fossil fuels, gaining energy independence and reducing their energy bills. But as Figures 1 and 2 show, this will be a long-term process.

But there are already a number of countries, such as Brazil, Costa Rica, New Zealand and Kenya, that generate more than 80% of their electricity from a combination of hydro, geothermal, wind, biomass and solar power.

Another factor with impact on global geopolitics is energy security. Concerns over energy security have marked the conduct of international relations, the formation of alliances, the protection of national interests, and defence planning. Oil interests have shaped the relations between the US and the Middle East for decades. In the longer-term one possible consequence of energy transformation will be to reduce the geostrategic importance of oil and gas as tools of foreign policy.

Energy security is driving major economies such as China, India and Japan to increasingly turn to indigenous resources for their energy and develop deeper ties with energy supplier countries.

In a renewable energy economy, most countries will be able to achieve energy independence, by being able to more on indigenous renewable resource. They will have greater energy security, more freedom to take the energy decisions that suit them and will also be able to pursue their strategic and foreign policy goals more independently. In addition, they will not need to cushion their economies from global fuel price volatility, often as a result of remote geopolitical events. Transition to renewable energy will also create new trade patterns.

These are factors that will not merely influence the balance of power between countries, they will also reconfigure alliances and trade flows, and create new interdependencies around electric grids and new commodities, such as materials required for batteries. Conversely, alliances built on fossil fuels are likely to weaken.

In addition, the energy transformation will also create opportunities to overcome root causes of geopolitical instability and conflict, especially those associated with fossil fuels. As Amin said “It is imperative for global leaders and policy makers to anticipate these changes, and be able to manage and navigate the new geopolitical environment.”

Impact on natural gas

However, as Figure 1 shows, fossil fuels, and more so natural gas as the cleanest, will be required for a long time to come, to 2050 and probably beyond. The rise of renewables does not mean that the decline of the fossil industry is inevitable. Renewables are not ramping-up quickly enough to replace fossil fuels – at least for the foreseeable future.

It is for this reason that the European Commission sees natural gas playing an important role in energy transition at least to 2035. But nevertheless EU’s 2050 energy strategy aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by between 80% and 95% when compared to 1990. A key question is what happens to gas between 2035 and 2050? By then, cheap renewables, backed up by storage, are likely to dominate power generation at the expense of gas.

Figure 1 also shows oil peaking earlier than natural gas and declining faster. As a result, Shell and other majors are in the process of growing their natural gas portfolios relative to oil. In addition, Qatar’s recent decision to leave Opec to focus more on export of LNG, illustrates the challenge that Opec faces amid future and potential structural changes in the oil market.

Shale gas will account for ever more of the supply picture, with US shale development on track for huge growth in the coming decades, with the potential to account for about half of global oil and natural gas growth by 2025. This is already impacting global gas markets and related geopolitics.

Another energy transformation with major geopolitical implications is the increasing use of LNG to transport gas geographically more widely – in effect commoditising gas.

Natural gas flows through pipelines are in one direction, from an exporter to an importer, and require fixed transportation infrastructure. This poses limitations, lack of competition, price inflexibility and can conflicts that do not happen with LNG.

The movement towards a more interconnected global gas market, as a result of growing trade in LNG, intensifies competition among suppliers, while changing the way that countries need to think about managing potential shortfalls in supply. In fact LNG is expected to be providing most of the growth in global gas trade, with its share expected to increase from 42% in 2017 to almost 60% by 2040.

In the longer-term decarbonisation of natural gas to produce hydrogen, without CO2 emissions, is a technological option that looks increasingly viable and offers a way forward for gas in a carbon-neutral world, especially when used in regions that possess abundant supplies of renewable energy. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) may also be an option.

Implications of GET

While global energy consumption continues to shift to Asia, increasingly geopolitical factors are exerting new and complex influences on energy markets, underscoring the critical importance of energy and supply security.

Food security and energy are strictly connected: three quarters of the world’s poor live in rural areas and rely on agriculture. Renewable energy solutions can be life saving in this context.

Globally, including China and India, the tide of public opinion is on the turn, favouring stronger action to mitigate climate change and air pollution. This is likely to lead to a faster-than-forecast adoption of low carbon and renewable energy, mainly at the expense of coal and natural gas in power generation, and of crude oil for transportation.

The issue of acceleration of energy transformation in view of climate change is becoming a topic in itself. However, while most countries recognise this, and the imperatives of energy transformation in terms of climate change and economic benefits, technological challenges and international cooperation are critical in order to ensure an adequate pace of change. This still requires fundamental shifts in strategies, policies, investments and mindsets.

As Amin said: “Those that lead in clean technology and investments stand to gain the most from energy transformation. We are very quickly, moving away from energy geopolitics characterized by scarcity and conflict, to an energy future built on abundance and peace.” The world that will eventually emerge from the renewable energy transition will be very different from the one that was built on a foundation of fossil fuels.

It is this energy abundance, created by the inexorable penetration of global energy demand by renewables, that is increasing energy competition and is bringing energy costs down globally.

The report findings have the potential to alter relations between states and bring out new challenges in global geopolitics. But at this stage, it is only a beginning.

More will need to be done to identify risks associated with energy transition and what policies will be needed to address these and ensure a rules-based, legally-driven, transition backed-up by international governance structures. But, as stated earlier, change is coming and it is coming quickly.

Transformation driven by renewables will be disruptive and will require a high degree of confidence building and trust among nations, well-regulated markets and rules based cooperation. But ultimately the environmental and socio-economic benefits of energy transformation far outweigh the challenges – provided that the right policies and strategies are in place.