Gazprom and its domestic challengers [NGW Magazine]

The past decade was a tough one for Russian gas giant Gazprom, having its modus operandi in the European Union repeatedly questioned as the market there grows ever more competitive. The global economic crisis and the consequent drop in European gas demand a decade ago coincided with rising threats from LNG producers in the US and Qatar.

This has powerfully affected Russia’s gas exports to the region, which fell from 158bn m³ in 2008 to around 100bn m³ in 2010, according to Gazprom Export’s figures.

The situation was further aggravated by weak price; and the European Commission’s push for market liberalisation and diversification of gas supply sources have additionally weakened Gazprom’s positions as the main EU’s gas supplier.

On top of that, events in Ukraine have downgraded foreign perception of Russian gas, making extra imports less attractive despite their low cost.

And while Gazprom makes every effort to preserve its market share in Europe, its position at home is scarcely better, since other gas producers have been seeking for some time now to strengthen their grip on the market at its expense.

After the break-up of the USSR, competition in the domestic gas market was never prohibited but the extremely low state regulated prices meant it was not economic for the private gas companies that emerged in the early 1990s to compete, thus allowing Gazprom to enjoy its quasi-monopoly position as a distributor of gas.

This picture started gradually to change when the Russian government, after years of delay. set up annual price increases until they reached net-back parity with Gazprom’s export prices. As domestic prices began to rise consistently – although not so fast as projected in Russia’s 2003 Energy Strategy – the Russian market became much more attractive for these producers, as they now had the chance to market their gas for a reasonable profit margin.

The companies started further to expand their resource base buying assets, mainly in the gas-rich Western Siberia region, near Gazprom’s trunk pipeline system for further transport to end-users. The right to this capacity is over 20 years old but it was generally left to the goodwill of Gazprom, which enjoyed its exclusive ownership of all trunk pipelines within the country, to decide whether to provide third-party suppliers with transport capacity; and if so, how much.

Nevertheless, this strategy has paid off as the companies managed to boost output and sales. By 2006 their market share rose to 14%, from 6% in 1996.

Until the mid-2000s, this loss of market share was too small to trouble Gazprom, which still sold six out of every seven units of gas at home, as well as keeping its hands on the domestic valves. This meant that the producers had to sell some gas to Gazprom, which could then fulfill its contract obligations in a growing domestic market. Historically, three huge low-cost gas fields in Western Siberia – Medvezhe, Urengoi and Yamburg – made up the bulk of Gazprom’s gas production, and more than three quarters by the turn of the century. This allowed the company to subsidise households and major energy users at home, as well as to meet its long-term take-or-pay contract commitments with European gas merchants.

With a gradual drop in gas production from these fields at the beginning of the century, Gazprom was facing up to the need to start investing in new, high-cost gas fields on the Yamal Peninsula and the Arctic. In this context, the growth in third-party gas production was more than simply welcomed by Gazprom. It was the cheapest way to fill the gap in the domestic supply-demand balance and allowed it to export more to Europe, where prices are the most profitable.

But rising domestic gas prices brought out the latent ambitions of the independent gas companies and created a business climate where they could start to compete rather than merely co-operate with Gazprom.

This eroded the earlier system whereby the companies simply sold their gas to Gazprom. Today, there are two distinct categories of players in the domestic gas market alongside Gazprom. To the first belong the mostly privately-owned producers which received their first upstream licences during the gas sector reform in 1992, such as Novatek.

The second comprises Russian oil companies, which have developed a gas business, thanks either to their significant associated gas production, or to some gas assets they acquired at the beginning of the 1990s. Government-owned Rosneft and independent Lukoil fall into this category.

Unlike the more conservative Lukoil, which developed a quite close relationship with Gazprom at home but also abroad – they are both active in Uzbekistan, for instance – Novatek and Rosneft became Gazprom’s real competitors, after calling for over a decade for reforms to curtail Gazprom’s power.

Competition in the Russian gas market between Gazprom and the other producers revolves essentially around the access to huge energy-consuming and, critically, solvent buyers. The Russian dual market system with state-regulated gas prices on the one hand and free market prices on the other, encourages this competition.

Since the dissolution of the USSR, the residential sector has had gas only at regulated prices, set by the federal antimonopoly service (FAS) but varying from region to region. Gazprom is the single gas distributor in this market (see separate feature). The huge industrial enterprises and power plants may purchase their gas from Gazprom on the regulated market – according to quotas negotiated beforehand – and from the independents on the free market. The industrial sector is thus the real battleground between gas suppliers, since these are large buyers who not only use a lot of fuel; they also pay for it consistently.

Here, Gazprom’s market power is rather limited as the company has no right to sell its gas at a price below that set by the state, while no such regulations apply to the independents.

To expand their market share and further consolidate their positions, Novatek and Rosneft began to offer more flexible prices and supply volumes in their gas contracts. Starting in 2012 both Novatek and Rosneft did well as most of Gazprom’s contracts with major customers were up for renewal that year.

Thus, Novatek managed to sign a 15-year contract (2013-2027) with E. ON Russia – now Uniper – for supplies to four of its power plants. The contract replaced a similar one with Gazprom that expired in 2012 and which E.ON refused to renew because Novatek “offered better contract terms”. The same year, Novatek signed a five-year contract with another of Gazprom’s customers, Russia’s largest mining and metallurgical company Severstal, for 12bn m³/year from 2013. Other major losses for Gazprom were sales agreements that its rival signed with the Magnitogorsk metallurgical plant (2012-2022), Fortum (2013-2027), the Novolipetsk metallurgical plant (2016-2021), Enel Russia (2016-2018, renewed for 2019-2021) and EuroChem (2018-2024).

Rosneft appeared to be no less successful in its quest to lure customers away from Gazprom. In 2012, it signed a three-year contract with E.ON, now Uniper, which it subsequently extended up to 2020. The same year, it signed a 25-year contract with Inter RAO, Russia’s largest electric power company, for 875bn m³ of gas – around 35bn m³/year – to be supplied from 2016 to 2040.

To retain its dominant positions in the market, namely in the high-yield areas near the main production centres, Gazprom has repeatedly attempted to reverse the discriminatory measures in the domestic market to compete on equal terms. To this end, the company asked the government for the right to offer discounts to consumers. Gazprom’s position found support from FAS, which even proposed setting up a pilot project on industrial gas price liberalisation in three gas producing regions: Khanty-Mansiisk and the Yamal-Nenets and Tyumen regions.

So far the company’s efforts have been unsuccessful, with the energy ministry worried that the experiment could simply drive out independent suppliers from these regions, as Gazprom could offer better prices than Novatek and Rosneft. The only positive change has been the abolition on of state regulation of prices for liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is produced by Gazprom for commercial supplies. That happened November 30, 2018.

Novatek’s and Rosneft’s strategy of enticing away Gazprom’s clients is largely supported by economics, as the production portfolios of both companies are significantly cheaper to develop than Gazprom’s. Added to which, Novatek and Rosneft benefit from lower taxes (no mineral extraction tax) and zero maintenance costs, although both still pay higher transport fees than the subsidiaries of Gazprom for the use of trunk pipeline system (see box).

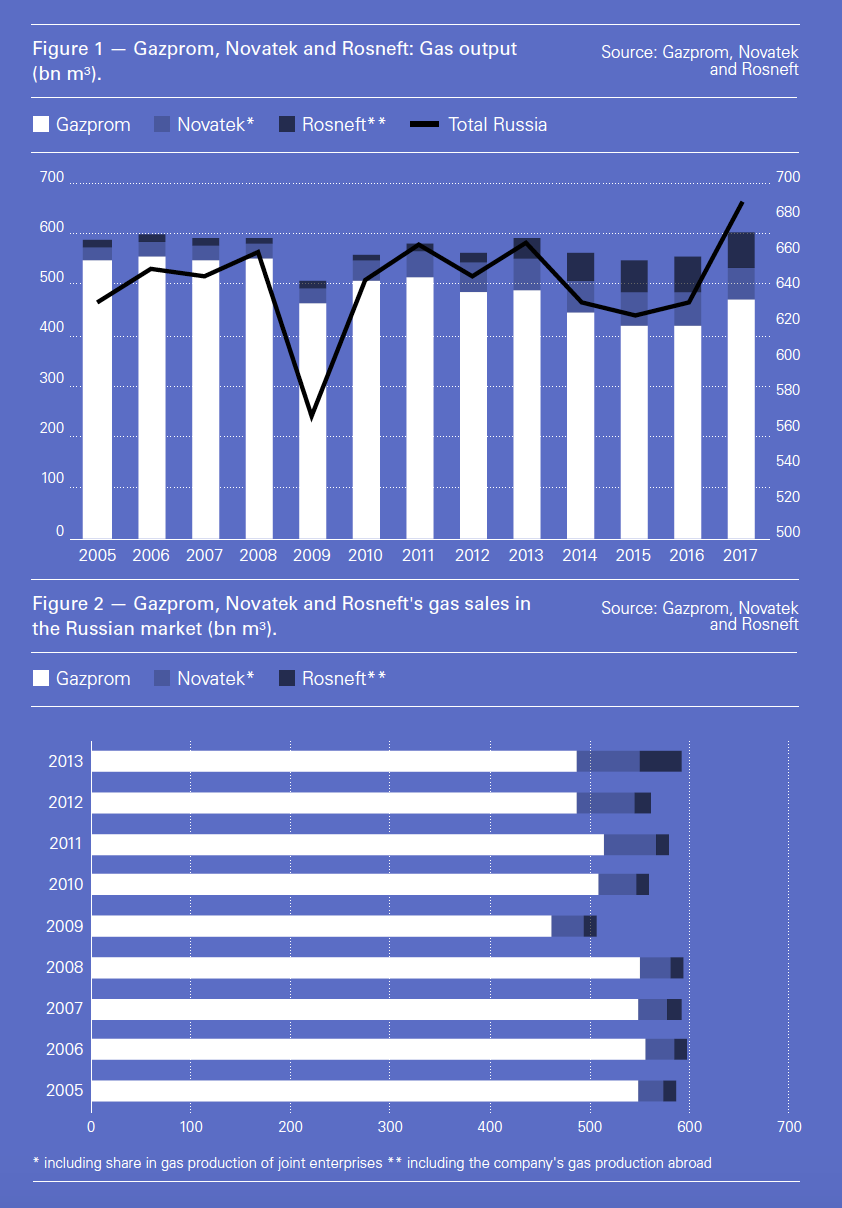

These competitive advantages allowed them to make substantial increases in output. Novatek’s has grown from 25.4bn m³ in 2005 to 53.5bn m³ in 2011and 63.4bn m³ in 2018.

This extensive growth is explained by the acquisition of several hydrocarbon exploration and production licences in the territory of the Yamal and Gydan Peninsula and in the waters of Ob Bay, where the main resource base of the company is situated. Gas production was further boosted by the takeover of companies Evrotek in 2016 and of Severneft-Urengoi in 2017.

As for Rosneft, the company’s domestic production amounted to only 13bn m³/year in 2005 and stayed at that level until 2012. But its purchases of independent oil company TNK-BP, which had vast gas resources within the country, Itera and Rospan helped it to produce 42bn m³ in 2013 and 68bn m³ in 2016. That made it Russia’s largest gas producer after Gazprom. According to the company’s latest annual reports, it expects to produce 100bn m³ by 2020.

This growth matches the slow but steady drop in Gazprom’s gas production, from 89% of Russian output in 2001 to 75% today.

The significantly lower MET paid by Novatek and Rosneft allows them bigger sales margins. Today, they supply over 120bn m³/year of gas in the domestic market. The share of Novatek and Rosneft in the market is 20% and 17% respectively, while Gazprom’s has fallen from 95% in 2001 to less than 55%.

According to some Russian gas experts, the narrowing of Gazprom’s market share domestically does not present the worst scenario for the company, since Gazprom can focus on more profitable export markets in Europe and Asia.

The company’s main task is not to retain a dominant share in the Russian market, but rather to find ways of stopping competition with Novatek and Rosneft abroad. The constantly growing resource base of independent companies requires monetisation. Since the companies cannot do it at home, given stagnant gas demand and low prices, they need access to export markets. In December 2017, the first stage of Novatek’s Yamal LNG plant was launched; and the final investment decision for Arctic LNG 2 is expected by the time the concrete pouring starts this July. When that starts up on the Gydan Peninsula, in 2022-2023, there may be a situation where Novatek’s LNG can compete with Gazprom’s pipeline gas both in Europe (via Nord Stream-1 and 2) and Asia (via Power of Siberia). The implementation of Rosneft/Shell Sakhalin-1 LNG project, which targets primarily Asian markets, can further increase competition in Asia. This in turn will lead to a substantial drop in gas prices and consequently a reduction in Gazprom’s export revenues, a scenario which the Russian state has been putting off since exports first began 50 years ago.

Dodging Russian taxes

Significant incentives mean that Russia's major gas producers, Gazprom and Novatek, are better positioned than many of their peers in terms of their future tax burden, according to analysis published by GlobalData.

The company's latest thematic research report: 'Taxation in Oil and Gas' reveals a high degree of variation in the upstream fiscal regimes and tax burdens faced by leading integrated and independent oil and gas producers. Novatek faces the lowest burden among leading independents, while Gazprom comes third among the top 15 integrated producers for lowest remaining fiscal take (the percentage of future field cash flows allocated to the government through royalties, production shares and other taxes).

Analyst Will Scargill said that the government has offered “massive tax breaks for major projects. Among the biggest beneficiaries are new fields in the North of the Yamalo-Nenets region, which will provide gas to support Novatek's LNG projects and Gazprom's exports to Europe."

He told NGW that Gazprom’s oldest fields enjoyed a tax discount to incentivise maximum output that offset the relatively high burden. As its major shareholder, the government has to weigh up the benefits of higher taxes or higher dividends, as well as the threat to profits on exports if more Russian gas is sold competitively by other companies.

And as Gazprom still has the pipeline export monopoly, it can make a decent margin on sales to Europe, even with a 30% export duty, Scargill said. Novatek, whose exports of LNG to Asia are so critical to the government, has exemptions from most taxes for upwards of ten years.

– William Powell