Gas eyes UK power chance [NGW Magazine]

Japanese technology giant Hitachi’s recent cancellation of its planned 2.9-GW Wylfa Newydd nuclear power plant in north Wales and its 2.9-GW Oldbury C plant near Bristol, England continue an ominous trend for nuclear power.

They follow Toshiba’s decision to abandon the 3.8-GW Moorside nuclear project in Cumbria in November 2018.

Although Hitachi noted that the Covid-19 pandemic had made the business environment “increasingly severe,” the project was already hanging by a thread after its suspension 20 months ago which followed a lack of government funding.

The UK has around 9 GW of installed nuclear power capacity, but much of this is expected to gradually retire over the next decade. The first 1.6-GW unit at EDF’s Hinkley Point C plant in Somerset may replace some of this capacity – it is aiming for completion by end-2025 – but the project seems prone to delays and cost overruns. EDF's 3.2-GW Sizewell C project may get the go-ahead, but it will take at least nine and possibly as much as 12 years to build the plant. EDF also has plans for the 2.2-GW Bradwell B plant in Essex, but the project is so far only at the consultation stage.

One of the great challenges for nuclear power projects is high start-up costs, which means government support in some shape or form is needed.

The government is supporting Hinkley with a £92.5 ($120)/MWh price guarantee, a ‘contract for difference’ (CFD) indexed to inflation over 35 years that was agreed by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. The new Conservative government that succeeded it under a new leader subjected the contract to a summer-long review in 2016, but despite an avalanche of consultants’ reports saying it was over-priced, it let the deal and the price support stand.

Among other things, Theresa May’s government was committed to cutting carbon emissions and phasing out coal from the power mix, leaving the country in need of firm, low-carbon power supply.

According to research by ratings agency Moody’s, the CDF is worth £100/MWh in today’s money, more than twice Moody’s forecast for near-time power prices. The government would not offer a similar price guarantee for the £20bn Wylfa project, and it is doubtful whether it will do the same again for other nuclear projects.

"I would be wary of betting on new nuclear FIDs in the UK post-Hinkley. If you look at new EPR [pressurised water reactor] projects across Europe they are all delayed, such as in Finland and France. These are big plants and the costs are massive. Plus the permitting process is very long," Fitch Ratings’ head of utilities Josef Pospisil told NGW.

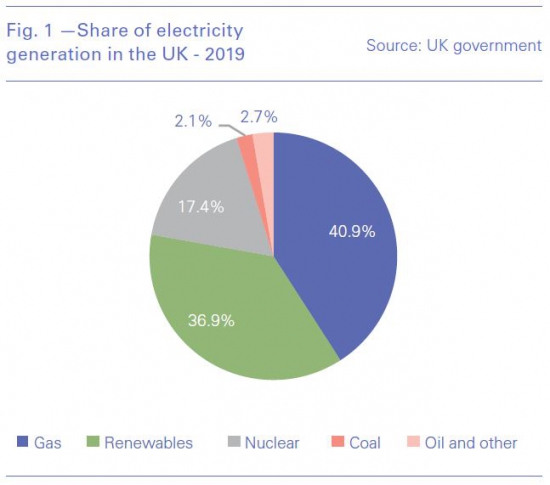

Additionally, coal is being squeezed out of the UK’s electricity mix for market reasons. The last remaining plants will close by 2025 at the latest, but probably much earlier – perhaps by 2022. RWE shut its 1.6-GW Aberthaw coal-fired power plant in South Wales in March and SSE shut its 1.5-GW Fiddler’s Ferry plant in Cheshire around the same time. The closures leave the UK with only four operating coal plants and they are little used. Only 2.1% of electricity in the UK was generated by burning coal in 2019 compared with over 40% from gas, according to government data.

Higher prices for carbon allowances under the EU ETS and the UK’s £18/metric ton carbon price floor coupled with cheaper gas relative to coal has squeezed the profit margins for coal-fired plants. At the same time, the share of renewables in the generation mix has grown over the last years, and it is expected to continue to increase. In 2019, over 37% of electricity generation was from renewables including wind and solar.

Gas eyes market share

Natural gas looks well placed to complement the renewables boom particularly against the backdrop of the coal phase-out and faltering nuclear projects. For example, Drax is building a 3.6-GW gas-fired plant in North Yorkshire which would be Europe’s largest. The first 1.8-GW unit could be operational by October 2023, but a final decision hinges on capacity payments.

Moreover, SSE is building the 840-MW Keadby 2 gas-fired power station in North Lincolnshire which is expected to be commissioned in 2022. The plant secured a 15-year capacity payment contract in the UK capacity auction in March after failing to secure contracts in the previous two auctions. UK capacity auctions resumed this year after a suspension which lasted for almost a year after a challenge by Tempus Energy before the European Court of Justice. Settlement prices have come out relatively low in recent auctions, but capacity payments are nevertheless an important tool in keeping existing gas-fired plants on the grid and securing investment in new plants.

That said, there are signs that investor confidence in new gas-fired plants are on the decline. Analysts at Frontier Economics have noted that the two capacity auctions held so far in 2020 saw a substantial drop in participation from new-build CCGTs, with around 2 GW and 7 GW taking part in each auction. This compares with 14 GW of new-build CCGTs participating in the T-4 auction in 2018. One of the drawbacks for investors is that the renewables expansion will likely keep a lid on wholesale power prices going forward. Moody’s forecasts that renewables will account for half of electricity generation in the UK by 2025. But the proportion is less meaningful than the overall effect that privileged renewables have on other generators on the system – in particular their unpredictability and instability.

Open-cycle gas turbines have the flexibility to back-up renewables as they have very quick start up times – no more than a few minutes – but admittedly they also have higher fuel costs than CCGTs. Reciprocating engines – small plants which are relatively cheap to build and start up in seconds – seem to be in the money. The downside is the relative inefficiency. But they secured 715 MW of capacity contracts in the T-4 auction in March this year, according to Frontier Economics.

Great Britain is building plenty of interconnectors with other countries which should help mitigate security of supply concerns. A new 1-GW link with Belgium is already up and running and a 1.4-GW interconnector from Norway is expected to be commissioned next year.

A side benefit of that cable is the ultra-low carbon footprint of electricity from that hydro-rich country, although the UK government does not consider the carbon content of imports in the daily mix when it trumpets the decline of fossil-fuel generation.

New links with France (3.4 GW), Denmark (1.4 GW) and Ireland (0.5 GW) are also under way. The UK has been a net importer of electricity since 2010 and this trend is expected to continue, which is bearish for prices. However, there are developments in other countries to look out for. Belgium, for example, has said it will phase out nuclear power for good by 2025: nuclear accounts for half that country’s generation capacity. Moreover, Norway may be short of power during dry years when hydro reservoir levels are low; this was seen as recently as the summer of 2018.

UK climate policy will also be decisive in shaping the future for gas-to-power projects. Gas-fired power plants may have to be retro-fitted with expensive carbon capture technologies in the longer term in order to contribute to the net-zero 2050 target. In the shorter term, carbon pricing will be key. The UK is expected to drop out of the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) by the end of the year. It is still an open question whether it will create a national ETS – with or without linking – or instead opt for a carbon tax.

Stakeholders in the UK energy industry had until September 29 to respond to the government’s consultation on the proposed carbon tax. The tax would be determined by the average EU ETS price with the possibility of slight downward adjustments. Many expect EU carbon prices to rise in the coming years as fewer allowances will be available in phase 4 of the EU ETS which starts next year. A relatively high UK carbon tax – reflecting higher EU carbon prices – would not challenge only the few remaining coal plants. It would also mean older gas-fired plants could struggle to make a profit without capacity payments.

Nevertheless, natural gas seems likely to continue to play a major role in UK power in the foreseeable future. The renewables expansion may eat into its market share, but the flexibility of CCGTs will be needed to cover for intermittency. If more nuclear projects are scrapped and coal is phased out earlier than 2025, then CCGTs may be able to defend or even increase its current market share at least in the medium term.

"Gas-to-power demand in the UK will remain significant in the short-term. It may even grow over the next 5-10 years. Beyond that, it depends on policy choices in terms of decarbonisation. But even then, it seems at least some gas will be needed as it is difficult to see how new nuclear projects can be commissioned," said Pospisil.