From the editor [GasTransitions]

This means you can fall into the trap of being over-optimistic and believing that we will have a new energy system tomorrow or next year. But you can also fall into the trap of thinking that nothing is really changing.

After all, you might say, solar and wind power still account for very little, despite years of public support. And how many EVs do you see on the road?

Yet that perspective could be equally misguided. The energy transition is happening. Slowly, yes. But surely.

Thus, for example, Wood Mackenzie has just published a report on the future of power system flexibility in major European markets. This finds that for now, “gas peakers” are “more essential than ever” to balance the grid in countries like Germany, the UK, France, Italy and Spain. However, by the end of the decade, battery storage will be the cheapest option, “resulting in a cloudy outlook for any new future gas peaking turbines,” as Wood Mackenzie analyst Rory McCarthy told GreenTechMedia.

In the U.S. and Australia gas peaking plants are facing similar challenges.

European oil and gas companies have gotten the energy transition message by now. Italian oil major Eni announced on 4 June that it is splitting up the company into two business groups: “Natural Resources”, which will include oil and gas, including CCS, and “Energy Evolution”, focusing on power generation and the switch from fossil fuels to “bio, blue and green”.

“This new structure reflects Eni’s pivot to the energy transition. An irreversible path that will make us leaders in decarbonized energy products,” saidChief Executive Officer Claudio Descalzi.

However, Eni is hardly a leader: it is merely following the example of Statoil (which even changed its name to Equinor), Shell, Total and BP, which have all set up “new energy” divisions in recent years. In fact, it probably won’t be too long before these companies will come with announcements of new reorganisations that will see their “new energy” units fully integrated into the company structure. They won’t be “new” forever.

To illustrate this point: when I asked Oliver Bishop, head of Shell Hydrogen, in an interview for Gas Transitions featured in this issue, whether the company’s hydrogen unit, now part of Shell New Energies, should not be “upgraded” to become part of the major activities of Shell, he corrected me and told me I had it the wrong way around. Shell New Energies, he said, is already part of the major activities of Shell.

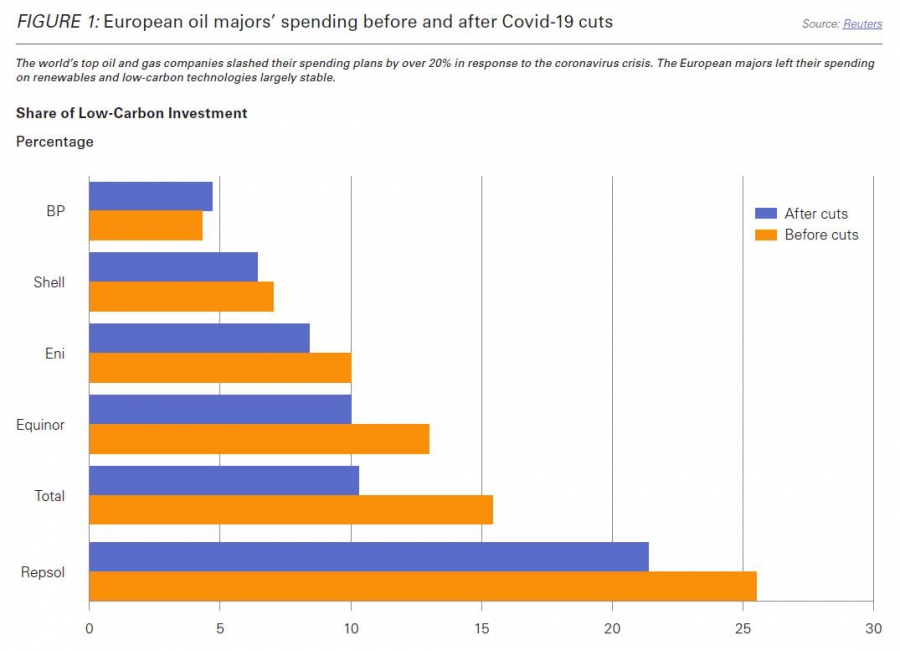

It is true that unlike their European counterparts, U.S. oil companies are still pretty much sticking to the old ways. Reuters investigated the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on oil companies’ capital spending and concluded that whereas “Europe’s top five producers – BP, Shell, Total, Eni and Equinor – are all focusing their investment cuts mainly on oil and gas activities, and giving their renewables and low carbon businesses a relative boost”, U.S. oil companies “are taking a different path… investment in business ventures outside petroleum hardly register.”

Personally I don’t doubt that the European companies are on the right track. That does not mean there is no future for natural gas. It does mean the future will look very different, and the existing oil and gas companies will only be part of it if they manage to adapt to the transition that is going on. Slowly. But surely.

Karel Beckman, editor-in-chief

karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com