Fresh hope for Nigerian gas [Gas In Transition]

The war in Ukraine and desire of most European countries to eliminate imports of Russian gas have prompted buyers to look anew at Africa’s considerable gas potential. Nigeria, already the continent’s largest LNG exporter, has the reserves to supply several new LNG trains and potentially support pipeline projects, if long-standing security and feedstock supply difficulties can be overcome.

High gas prices were already reviving interest in African gas reserves before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The executive vice president of the European Commission, Margrethe Vestager, held talks with Nigeria’s vice president Yemi Osinbajo in February to discuss increased LNG supplies. Following the invasion on February 24, that interest has intensified.

Executive Chairman of the African Energy Chamber, AJ Ayuk, who has previously been critical of EU lobbying to reduce oil and gas investment in Africa on climate grounds, said: “We have had various communications and various bilateral discussions with energy ministers from at least nine European countries, where we’ve had really fruitful conversations. This has never happened in the past.”

Major export potential

Africa’s geographical location – and particularly that of West and North Africa – makes it a viable alternative gas supplier to Russia for Europe.

Analysts Rystad Energy forecast that total African gas production will increase from 260bn m3 this year to 335bn m3 by 2030, exceeding 470bn m3 by the late 2030s. Siva Prasad, senior analyst at Rystad Energy, said: “Existing pipeline infrastructure from Northern Africa to Europe and historical LNG supply relationships make Africa a strong alternative for European markets, post the ban on Russian imports.”

Other trends should also encourage the development of African gas projects. Financing for African oil ventures has become increasingly difficult because of a desire to tackle climate change and this trend was also expected to have a growing impact on gas developments. However, the EU’s decision to categorise abated gas use as sustainable, alongside renewables, could ease funding difficulties upstream.

In addition, the withdrawal of Western oil and gas companies from Russia is likely to encourage them to look for potential projects elsewhere, including in Africa. The financial hit taken from pulling out of Russia has been offset by very high international oil and gas prices, which have greatly boosted revenues and therefore also investment potential.

Nigerian LNG

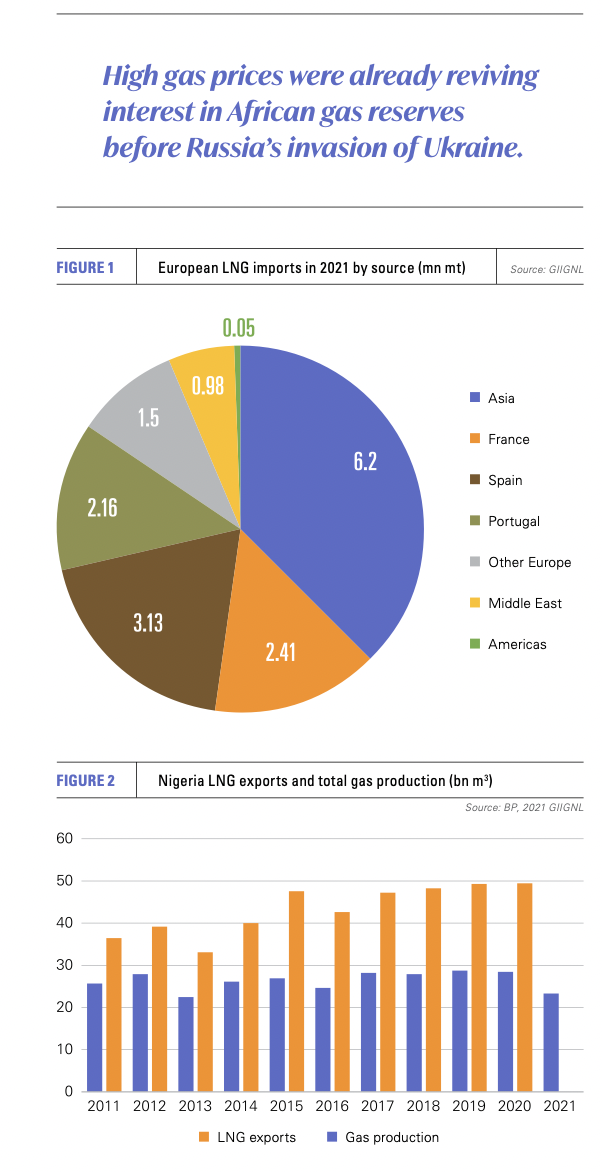

Nigeria’s existing LNG production comes from six trains at the Nigeria LNG (NLNG) plant on Bonny Island (see figure 1). Nigeria shipped 12.63bn m3 of LNG to Europe in 2021, mostly to Spain, France and Portugal, out of NLNG’s total production of 23.3bn m3 (see figure 2). The latter figure is down from 28.7bn m3 in 2020 and well short of nameplate capacity of 31bn m3/yr. According to local reports, the low utilisation rate reflects gas supply limitations from oil fields shut in as a result of OPEC supply restrictions.

Nigeria’s existing LNG production comes from six trains at the Nigeria LNG (NLNG) plant on Bonny Island (see figure 1). Nigeria shipped 12.63bn m3 of LNG to Europe in 2021, mostly to Spain, France and Portugal, out of NLNG’s total production of 23.3bn m3 (see figure 2). The latter figure is down from 28.7bn m3 in 2020 and well short of nameplate capacity of 31bn m3/yr. According to local reports, the low utilisation rate reflects gas supply limitations from oil fields shut in as a result of OPEC supply restrictions.

The Nigerian government believes LNG output could be higher. In April, Abuja accused NLNG shareholders, including TotalEnergies, Eni and Shell, of blocking moves by non-consortium members to supply gas feedstock to the project.

Nigeria is also looking to Equatorial Guinea as an option for increased LNG exports. In March, Abuja signed a memorandum of understanding with the government of Equatorial Guinea to supply gas to the country’s LNG plant and other industrial users on the Equatoguinean island of Bioko. The LNG plant produced 2.72mn mt of LNG in 2021, as against nameplate capacity of 3.7mn mt/yr.

Some deep water fields in the Gulf of Guinea are roughly equidistant between Nigeria and Bioko, so the proposal makes commercial sense. However, similar preliminary agreements have been signed in the past, but not followed through, so more progress is needed before the project can be regarded as likely to be developed.

Security and supply issues

Intense security problems in the Nigerian oil and gas industry have seen a gradual retreat of Western oil companies from Nigeria, particularly onshore, with assets sold and exploration reined in. In particular, little effort has been put into identifying and assessing potential gas reserves because of the difficulties involved in monetising production.

Under government pressure, NLNG has used some of its gas supplies to support the domestic market. It announced in January that it would increase LPG supplies to Nigerian customers and also intends to market up to 1mn t/year of LNG domestically from this July, although it remains to be seen whether high global prices will change that policy. The company said last September that it would acquire a small LNG carrier to supply Nigerian customers, while rail transport to supply LNG to cement producers has been suggested by federal ministers.

A further 8mn mt/yr capacity will be added to Bonny Island’s existing 22mn mt/year in any case when Train 7 is complete, but work on the project has been repeatedly delayed. NLNG took the final investment decision on Train 7 in 2019, with the engineering, procurement and construction contract awarded to a consortium of South Korea’s Daewoo Engineering & Construction, Italy’s Saipem and Chiyoda of Japan.

However, gas supply problems, objections by host communities and the COVID-19 pandemic have all held up construction of the $10bn project. The state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), announced in May that Train 7 would only be complete in 2026.

Aside from NLNG, at least a dozen other LNG projects have been planned over the past 20 years, but none have been developed. With 5.7 trillion m3 of proved natural gas reserves, the country certainly has sufficient gas to justify the construction of several new trains. However, Abuja has tried to ensure that domestic requirements are satisfied before new export capacity is built. Regulated low prices deterred oil companies from marketing associated gas in Nigeria; so much of it continues to be flared, despite repeated government edicts to halt the practice.

The new Petroleum Investment Law, which was finally passed in July 2021 after years of wrangling, should in theory enable fairer prices to be paid for gas supplied to the domestic market. However, it is difficult to guarantee supplies as the country’s oil and gas pipelines have been regularly bombed since before the turn of the millennium, often by the gangs who steal a substantial proportion of the country’s oil production. Gas pipelines are not bombed to enable theft, but in retribution for security operations against the militants, whose aims are often hard to distinguish from the activities of criminal oil gangs.

Piped options

Even if Nigeria is able to export more gas to European customers, there is some uncertainty over whether it will take the form of LNG or piped gas. Abuja was already keen to see progress made on the shelved Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline (TSGP) project, but efforts to develop it gained a great deal of intensity shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine.

The 4,128-km TSGP would run from Warri in the Niger Delta northwards through Nigeria and then across desert areas of Niger to Hassi R’Mel in Algeria. It is envisaged that the gas could then be piped to European customers via existing subsea pipelines that run from Algeria to Spain and Italy, if sufficient capacity exists. However, a new dedicated pipeline under the Mediterranean would also be an option.

NNPC and Algeria’s state-owned gas oil and gas company Sonatrach signed the original memorandum of understanding on the TSGP in 2002. A feasibility study completed by Penspen in 2006 suggested the project was both technically and economically feasible. The governments of Nigeria, Algeria and Niger signed an intergovernmental agreement in 2009, but the venture stalled from then onwards, probably as a result of difficulties in securing financing and because of security threats to gas supplies in Nigeria and from militant bomb attacks in the Sahara.

However, this February the three governments signed an agreement to set up a taskforce to restart the project. An updated price tag of $13bn for construction has already been floated.

A rival project would involve extending the existing West Africa Gas Pipeline (WAGP) up the coast of West Africa to Morocco and then on to Spain. In April, engineering firm Worley was awarded a $90m contract to provide front-end engineering design (FEED) services on a proposed 7,000 km Nigeria-Morocco pipeline. This route would be more expensive than previously-proposed shorter routes, but would avoid militant threats in the Sahara and Sahel.

On June 2, Nigeria's cabinet gave NNPC approval to enter into an agreement with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) on the development of a gas pipeline to Morocco, according to local press reports. This version of the pipeline would run 5,660 km through 15 West African countries. Nigeria’s petroleum minister Timipre Sylva was reported as saying that companies from a number of countries, including Russia, were interested in investing.

It is difficult to determine whether planned gas pipelines between Nigeria and Europe would make new Nigerian LNG capacity more or less likely to be developed. In most other producing states, the latter would be the obvious conclusion, as deciding to pipe gas between two points would indicate that it is either the more secure or cheaper option.

In Nigeria, however, there is sufficient gas to supply both pipelines and new LNG trains and Europe is likely to be willing to absorb as much gas as Nigeria can provide. A consideration on the part of producers should be that a pipeline cannot be redirected, if European gas demand falls as a result of its energy transition. Liquefaction plants are not similarly restricted, with volumes easily rerouted to Asia or other LNG consuming countries, if European gas consumption stalls.