French boost for biomethane [NGW Magazine]

The French government is backing measures to promote the production of biomethane, after French secretary of state for ecology transition, Emmanuelle Wargon, met with representatives from the country's emerging biomethane sector on January 14.

Wargon, whose brief includes energy, had requested the meeting to get an update on the progress made so far by the biomethane work group on goals adopted in March 2018 to speed up biomethane penetration as a renewable fuel.

Biomethane is grid-quailty gas that is derived from the biogas produced by the anaerobic digestion of organic waste from households, agriculture or sewage treatment. Typically water and other impurities are removed from biogas in methanisation plants to make gas with very similar properties to natural gas, meaning it can be safely injected into existing gas pipelines. As a renewable fuel it counts towards the revised EU target to source 32% of all energy from renewables by 2030, which is also the target under French law.

One of the methanisation working group's earliest achievements was the launch of a quality mark, qualimetha, for new biomethane production plants. To qualify, installations must adhere to all current regulation and be inspected to ensure compliance with a code of best practice, including continual improvement, good citizenry and environmental excellence.

“This will help reinforce the big advances in quality and give the biomethane sector a more professional standing,” Wargon said after meeting with the group in January.

Grid connection

A key priority in the coming months is to make it easier for biomethane production plants to hook up to the gas grid, as new grid injection rights for biomethane come into force this spring. From that point, dominant gas grid operator GTRgaz, and Italian-owned Terega, which operates in the southwest of the country, will be required to connect biomethane plants to the grid as long as they are close to existing infrastructure. And the grid operators must bear the costs of any additional infrastructure.

Grid connection costs for for industrial producers currently range between €176,400 ($201,000) for a single pipeline with a capacity of 705 m3/hr to €385,200 for a double pipeline with a capacity of 20,000 m3/hour. These are the rates published by GRTgaz, including all taxes.

The group is now working on plans to give biomethane producers a discount on grid access costs compared with those payable for conventional gas. These vary, depending on whether the installation is operated by an existing customer of the TSO, whether or not that customer has existing metering arrangements -- such as smart metering or hourly metering -- and whether it will be connecting to an existing grid connection point or a new spur.

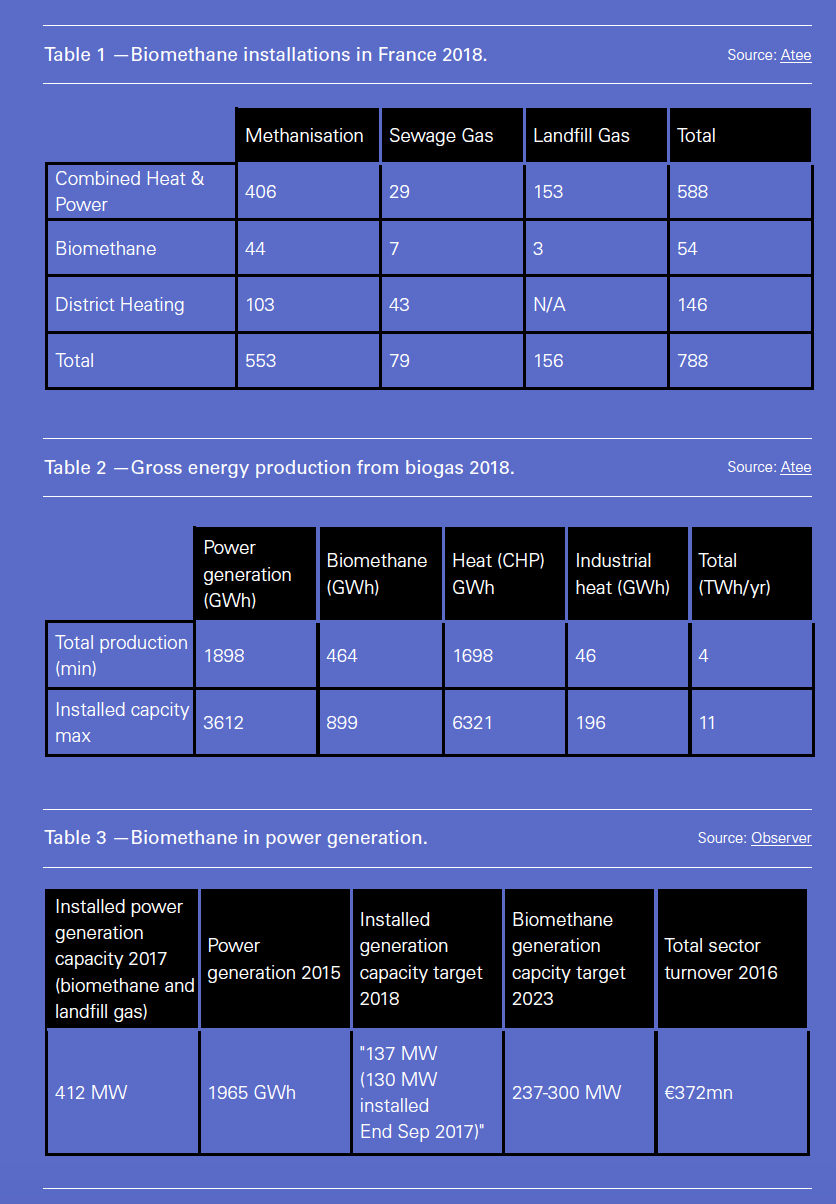

Additional priorities for the working group include simplifying the regulatory framework for biomethane production plants by classing them as plants that help protect the environment. Biogas produced at sewage treatment plants has the potential to grow alongside more established technologies to harness methane from landfill sites or manure and other agricultural waste. The first sewage gas entered the grid in 2015, and there were 79 sewage gas plants in operation by end 2018 according to the latest figures (see table 1).

Other initiatives to promote expansion include using biomethane to make bioNGV as a vehicle fuel for tractors and other agricultural machinery, easing restrictions on which waste can be mixed if organic only, and simplifying the consideration of biomethane under the country's water law.

Growing but still small

The biogas sector has already witnessed rapid growth, albeit from a low base. The total number of plants reached 646 at end June 2018, according to figures collated by the working group, and this had risen to 788 by the end of 2018 according to energy and environment technical association Atee.

While most of these use gas for power generation, the number of biomethane plants capable of producing grid-quality gas for injection into the network reached 76 by end-2018, with 661 new projects planned, according to the latest figures from GRTgaz.

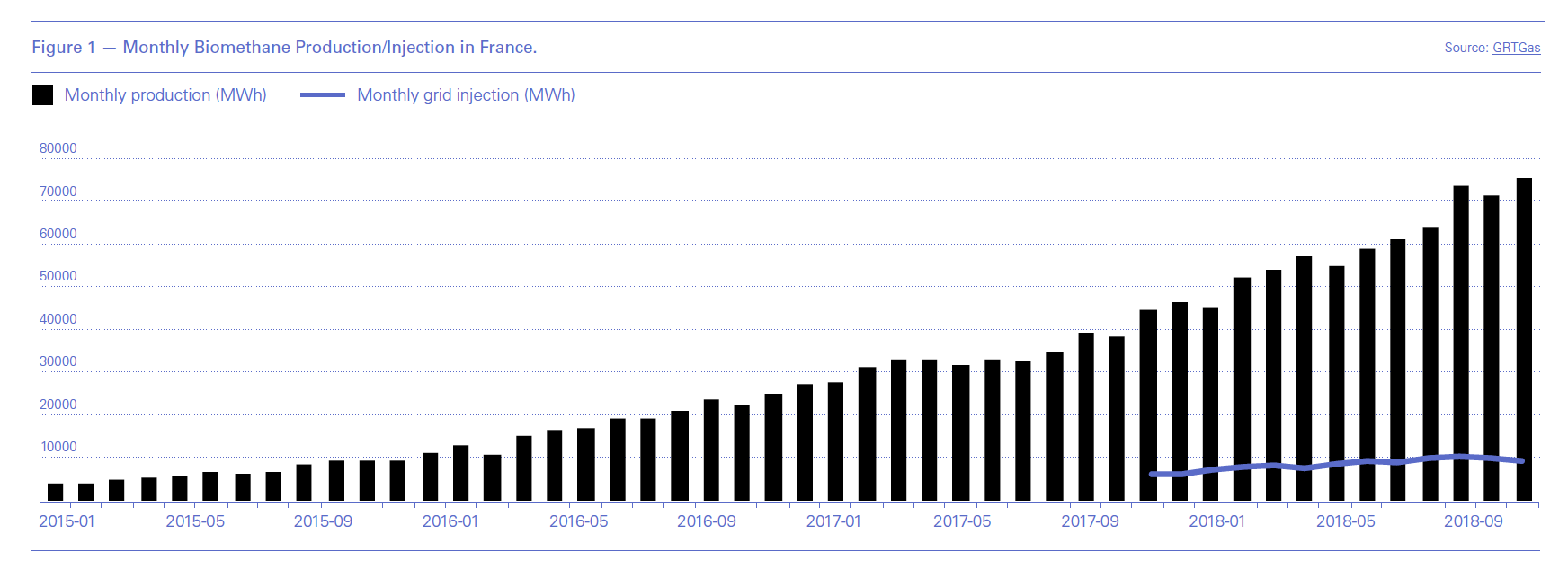

In terms of production, biomethane has grown exponentially in the last four years – from under 5,000 MWh/month in January 2015 to over 75,000 MWh/month in December 2018 according to GRTgaz. But only a fraction of this finds its way into the grid – 5,000 MWh/month in December 2017, rising to over 10,000 MWh in late 2018 before falling back to 9,000 MWh in December 2018. And with monthly gas throughput in the GRTgaz grid averaging 36.8 TWh in 2018, there is much potential.

Monthly Biomethane Production/Injection in France

“The sector is undergoing strong growth but is also at a crossroads with a number of challenges on the road ahead,” the working group stated in its initial assessment of the industry in 2018.

“These include ensuring the economic value of biogas as a feedstock for electricity generation, district heating, grid injection or as a biofuel in transport, as well as waste management (monetisation of organic waste and cutting back on landfill).”

So far biogas has been used mainly as a fuel for onsite power generation or combined heat and power generation.

And finally, the positive impact on climate change needs to be accentuated, as capturing methane as an energy source not only leads to reduced natural gas use, but also means less methane escapes into the atmosphere especially from agriculture: as a greenhouse gas, methane is 30 times as potent as carbon dioxide.

Scaling up

To help the sector grow beyond this initial start-up stage, the working group has proposed measures to promote bigger plants. These would ultimately lead to lower costs – with the government projecting that they will fall progressively to around €80/MWh from €100/MWh now.

“Getting to a larger scale requires us to develop bigger digestors and to go in search of new feedstocks like agricultural industrial waste, food waste, and sewage sludge” according to the working group.

To do this, the group advocates a raft of legal and regulatory changes to cut down on red tape. It recommends boosting the effectiveness of digestion by relaxing the rules on mixing of feedstocks – new rules of origin will make this possible by ensuring only organic waste is used. Restrictions still apply on mixing sewage sludge with other waste; and any proposals to mix these waste streams need local government approval on a case-by-case basis.

To speed up approvals, the government is to cut the permitting process duration from a year to six months, and will raise the threshold at which plants need to be reviewed under environmental protection rules from 60 metric tons/day to 100 mt/day. At the local level, each departement should introduce a “one-stop-shop” to handle all necessary permits and documentation, so that plant operators do not have to deal with multiple agencies. Finally, those plants under the 100 mt/day threshold are to be exempt from impact assessments or public inquiry under the country's water law.

Harnessing more biogas from sewage treatment has high potential given that only 22% of current sewage treatment plants harness biomethane in France. France could look to other countries like Sweden, which despite a much smaller population – 10mn versus 67mn -- was producing biomethane at 135 sewage treatment plants as far back as 2010, accounting for almost half the Nordic country's total biomethane production.

France is already one of the biggest producers of biomethane in the EU ranking fifth behind Germany, the UK, Italy and the Czech Republic but as it is the largest state in the EU and has the second largest population, and with its large agricultural sector, it has the biggest potential. And as a major importer of gas, the push to get biomethane into the French grid makes sense from a security of supply perspective as well as being a way to move towards zero carbon energy by 2050.

*The methanisation working group represents stakeholders across the biogas sector: industry associations, grid operators, financial institutions, government and public sector organisations, members of parliament and environmental campaign groups.