Fracking and Man Made Quakes

USGS to make separate risk map for man-made quakes

Federal officials are wrestling with how to account for the hazard created by man-made earthquakes, many of which are triggered by oil and gas activities.

In the past, the U.S. Geological Survey has generally excluded shaking related to industrial activity from its earthquake hazard maps. The maps project the likelihood of large, natural earthquakes and are used to develop building codes, plan roads and bridges, and set insurance rates.

But amid an increase in the number and severity of man-made quakes in oil and gas regions, scientists and engineers at the agency are developing a separate map that will include what geologists call "induced seismicity."

The traditional hazard maps, predicting the risk of natural quakes, are expected to be issued early next year. The map evaluating the risks of man-made quakes will be issued later in the year because the agency is still figuring out how it should be assembled.

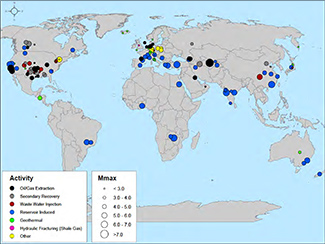

Locations of earthquakes linked by scientists to human activity as of last year. Click the map for a larger version. Map courtesy of the National Research Council.

"It's been the subject of rather intense discussion," said Bill Leith, senior science adviser for earthquake and geologic hazards at USGS headquarters in Reston, Va.

The traditional map of natural earthquakes is intended to guide decisions by architects, builders and others for as long as 50 years. The danger from man-made quakes might be much shorter than that, particularly if the activity causing it stops.

Still, man-made earthquakes are a hazard. Two people were injured and 14 homes were destroyed in a November 2011 quake outside Oklahoma City that USGS researchers have linked to deep underground injection of oil and gas wastewater (EnergyWire, March 27).

The amount of such deep injection has grown sharply with the nation's shale drilling boom, which has been driven by a hydraulic fracturing process that uses far more water than conventional drilling and creates far more wastewater. Most of that wastewater is eventually injected underground.

Geologists have known for decades that injection of any kind of industrial fluid deep underground can cause earthquakes. Injection of toxic fluid at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal was blamed for earthquakes near Denver in the 1960s.

Amid the boom in drilling, fracking and injecting, USGS scientists have identified a "remarkable" spate of earthquakes in the middle of the country. The agency says the rash of quakes is probably linked to human activity.

At the center of that trend is Oklahoma, which has one of the densest inventories of drilling wastewater disposal wells in the country. Oklahoma has ranked No. 2 among the lower 48 states for earthquakes both this year and last, after California. Since the beginning of 2009, 10 percent of the earthquakes in the country have been in Oklahoma (EnergyWire, Dec. 2).

In October, USGS declared that central Oklahoma is in the midst of a seismic "swarm." That prompted the state's insurance commissioner to urge people in the state to buy earthquake insurance.

Texas, which has probably the largest number of injection wells, had 18 earthquakes of magnitude 3 or greater from 2000 to 2008. This year alone, it has had 16.

USGS and other researchers have also identified "induced" or "triggered" quakes in Arkansas, Colorado and Ohio.

Moving beyond 'gray area'

The man-made quakes have become more severe and more common since USGS issued its last set of earthquake hazard maps about six years ago.

Previously, induced seismicity fell into a "gray area," said Mark Petersen, national regional coordinator of the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program. They were often excluded, but sometimes they were left in if they were thought to be a risk.

That gray area needed clearing up as the risk from man-made quakes grew.

"We don't want to put a map out that says 'no risk' or 'low risk' in Oklahoma," Petersen said.

Some USGS officials call the addition to the maps a new "product." Petersen calls it an "extra layer" of what's really a model rather than a map.

When the last set of earthquake maps came out in 2008, eight areas were excluded because shaking in the regions was traced to industrial activities. In next year's model, that number is expected to be about 20.

The 2011 Oklahoma quake, magnitude 5.7, is likely to be left out of the traditional evaluation of natural quake risks, along with another damaging magnitude-5.3 quake a few months earlier in Colorado. Other seismic events that would be evaluated in the new model include the Guy-Greenbrier earthquake swarm in central Arkansas in 2010, a series of earthquakes near Dallas-Fort Worth in 2009 and shaking since 2006 near the West Texas city of Snyder that has been linked to carbon-dioxide injection.

As they evaluate the risk to the public, scientists and others might look at whether the activity causing the earthquakes is likely to end quickly or whether the shaking is likely to become the "new normal," said Justin Rubinstein, a research geophysicist at USGS who is working on how to use the data from man-made earthquakes.

The changes could anger oil and gas companies who get blamed for the damage from the quakes, while proving a relief to those in construction and real estate that their area won't be deemed a natural earthquake zone.

Complicating matters, though, Oklahoma officials disagree with USGS on the 2011 quakes. The state geologist says there's not enough evidence to say that either was caused by injection of oil and gas waste.

Rubinstein said the separate analysis is intended to be somewhat "agnostic" on whether a quake was caused by a specific industrial activity. Instead, it is intended to include induced quakes, "potentially induced" quakes and sudden spikes that can't be accounted for in traditional models.

Karen Berry, interim state geologist in Colorado, said she supports treating the 2011 quake in Colorado differently than clearly natural earthquakes.

"Since we don't really know if the 2011 event was natural or triggered, it would be equally premature to update the seismic hazard maps solely based on this event," Berry said.

Mike Soraghan, E&E reporter

Republished from EnergyWire with permission. EnergyWire covers the politics and business of unconventional energy. Click here for a free trial

Copyright E&E Publishing