Financing Africa’s just transition [Gas in Transition]

The European Commission (EC) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) on January 29 formalised a new Financial Framework Partnership Agreement, aimed at expanding investments in infrastructure projects in Africa in strategic transport corridors, in energy and digital connectivity.

This follows the success of African countries at COP28, where their key demands, for a just energy transition, climate change finance and funding for adaptation, received strong support. This was led by the African Group of Negotiators (AGN), which demanded the right for Africa to develop its oil and gas resources, particularly gas as a transition fuel, to enable African countries to industrialise and then reinvest gains in low-carbon energy projects.

Africa’s population now exceeds 1.4bn people, and it is projected to reach 2.5bn by 2050. The continent has abundant natural resources, including minerals, oil and gas, that have become increasingly attractive to the rest of the world. But despite this, Africa is facing an energy crisis and severe energy poverty, with about 600mn people – over 40% of the population – lacking access to energy.

The agreement with the EC, and another one between USAID and AfDB, extended last year to 2030, could help combat energy poverty in Africa. But their main thrust is to support clean energy projects.

However, as the International Energy Agency (IEA) concluded last year, the future of Africa’s industrialisation relies on expanding use of its oil and gas resources, at least during energy transition – a view shared by the World Bank. In particular, natural gas will be key to the growth of the fertiliser, steel and cement industries, as well as to water desalination.

Developing these resources requires new infrastructure, including pipelines, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. But with international financial institutions diverting their attention to clean energy projects, and increasingly pulling away from funding fossil fuel projects, this is becoming a challenge.

This was confirmed in January by Namibia’s minister of mines & energy, Tom Alweendo, during a visit to London. He expressed concern that an increasing number of western financial institutions are refusing to fund fossil fuel schemes in Africa, jeopardising its need for economic growth and security, poverty alleviation, and job creation. He said “No nation has achieved industrialisation solely through solar or wind power,” and called on western countries to “rethink their strident opposition to fossil fuel investment in Africa.”

The G20 Compact with Africa

This started in 2017, with the objective of boosting investment in African countries participating in the G20 Compact with Africa (CwA) initiative. CwA requires the African Compact countries to reform their economies and promote good governance, thus becoming attractive to international investors. This then unlocks investments by companies from G20 states that boost the economies of CwA countries, while benefiting from enormous growth markets, including energy, and access to key raw materials.

German Chancellor Scholz has called for more private investment and closer cooperation with Africa in the fields of energy and hydrogen. He sees huge potential for growth, which is beneficial for both Africa and Europe. He said “For us, bringing Africa onside and strengthening our partnership for a sustainable economy for the future is not only an aspiration but an imperative.”

In 2022 the EC labelled investments in natural gas as climate-friendly. This and the need to ensure European energy security have kept the door open towards supporting natural gas projects in Africa and underpins German and Italian interest in the continent’s gas.

Financing Africa’s energy, oil and gas

Financing Africa’s energy, oil and gas development requires significant investment and policy coordination, with risk management and insurance playing crucial roles.

Also crucial to the success of securing investments is an understanding of the key country and regional risks associated with the development and execution of such projects.

Political instability, low creditworthiness of government borrowers, financial and economic risks and weak policies and regulations, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, increase risk levels and deter investors. Such risks, real or perceived, drive-up project costs.

Other risks include lack of infrastructure, poor access, inadequate labour, concerns about unexpected delays, environmental concerns, cost overruns and performance shortfalls that drive lenders to demand higher rates on loans.

Implementing de-risking measures across both private and public sectors can help improve the investment environment.

De-risking energy, oil and gas investments in Africa

Speaking at the 5th European Corporate Council on Africa and the Middle East summit last month in Rome, Claver Gatete, executive secretary of Economic Commission Africa (ECA), said that “up to 80% of the initiated infrastructure projects across Africa fail at the feasibility and planning stages.” This is a statistic that demonstrates the challenges in securing investments in African energy projects, especially large-scale projects where project risk is higher.

Gatete also said that “African countries are faced with unfair risk perceptions that deter investors and contribute to making the business environment unfavourable. We need to reverse this trend.”

He added that what is needed is “new and innovative financing sources that target investments better.” His recommendation is that “the public sector must step in to finance de-risking measures” that will make it more attractive for the private sector to participate. He suggested “we should be more intentional about leveraging foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance (ODA) to de-risk private investments” and make Africa a competitive investment destination.

In order to increase the pipeline of bankable projects, the ECA is conducting market and product analyses to help clarify where to invest. Well-designed financial incentives and implementation of policy and financial de-risking instruments also reduce risk and improve the investment environment.

FDI into Africa totals about U$40bn to $50bn annually. The target for ODA is 0.7% of developed country gross national income, but not many achieve that.

The AfDB together with seven partners set up the Africa Investment Forum (AIF) as a platform to aggregate bankable projects to make it easier to attract institutional investments.

AfDB president, Akinwumi Adesina, said “AIF has become today the premier investment platform to do anything on investment in Africa, and in the last four years, we have been able to leverage about $142bn of investment interest into energy, water and sanitation, infrastructure, and transport corridors.”

When it comes to oil and gas projects, Wood Mackenzie expects that about $300bn will be invested by the end of this decade. With western finance becoming scarce, increasingly the choice is to look for it locally or go east.

An example is Total Energies’ 1,400-km East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) from Uganda's oil fields to Tanga port in Tanzania. TotalEnergies and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) have made their final investment decision, but most western lenders have ruled themselves out of the project. Not surprisingly, Uganda, TotalEnergies and CNOOC sought Chinese support. Uganda's ministry of energy and mineral development confirmed in September that the Export-Import Bank of China and China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation have agreed to contribute about half of the $3bn debt finance needed to build the pipeline. The first shipment of 100km pipes arrived from China in December, enabling construction to start this year.

A new African bank to finance oil and gas

EACOP is a typical case where, under pressure from environmentalists, increasingly western countries, banks, lenders and insurers are turning their backs on investing in oil and gas projects in Africa.

This has led African institutions to develop their own solutions. In May last year, the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), based in Cairo, and the African Petroleum Producers’ Organisation (APPO) teamed-up to establish the African Energy Bank (AEB), specifically to raise funding for oil and gas projects and fill the void left by western lenders. They plan to launch it in June 2024.

Dr. Omar Farouk Ibrahim, APPO general secretary, said: “This is going to focus essentially on funding oil and gas projects on the African continent because [Western] funds have dried.” Special emphasis will be on addressing the funding challenges faced by national oil firms in Africa.

AEB aims to attract investment from countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait. It plans to become a key player in driving Africa’s economic development, ensuring that it capitalises on the continent’s abundant natural resources. For Africa, a just transition must take into account the need to develop oil and gas projects while striking a balance with the need for climate change mitigation.

These developments are offering a lifeline for African oil and gas projects, especially where they alleviate use of dirtier fuels, such as biomass, charcoal and coal, while meeting demand for cleaner-burning alternatives, such as natural gas.

Enter the dragon

And if it all fails, court the Chinese, who are still interested in investing in oil and gas projects in Africa. The continent is now the second largest exporter of oil to China, after the Middle East.

While, under pressure from climate activists, Western energy countries, companies and banks are becoming increasingly reticent to fund fossil fuel projects in Africa, Chinese companies are stepping-in to fill the gap.

As S&P Global pointed out, China has swapped cheap loans in Africa with energy investments in a bid to bolster its influence and secure future oil and gas supply. The three main Chinese companies, CNPC, CNOOC and Sinopec, together are now the fourth biggest investor in energy projects in Africa.

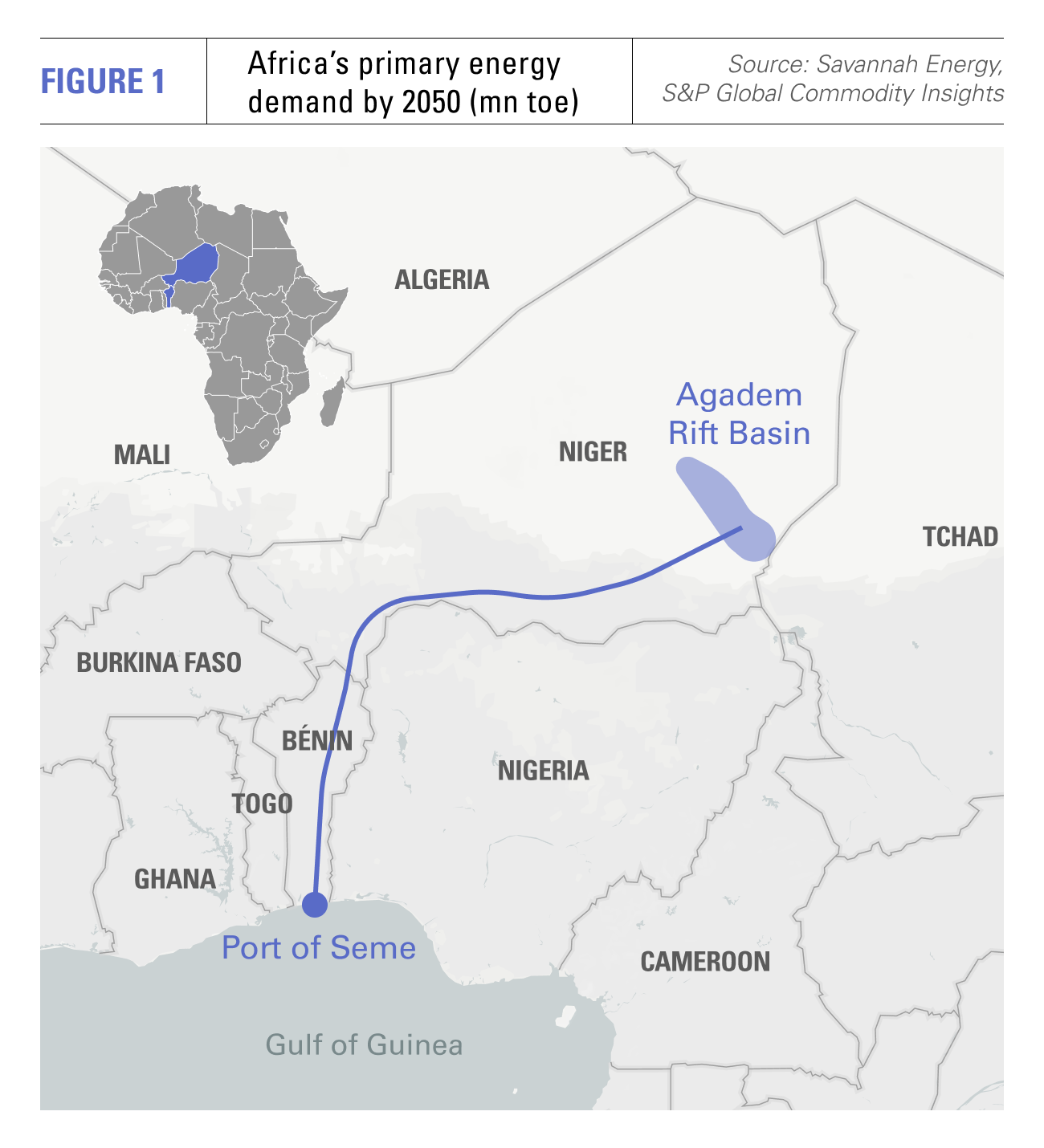

In addition to EACOB, examples of such projects are Mozambique's 3.4mn t/yr Coral Sul LNG project, and Niger's Agadem oil project and pipeline (see figure 1), commissioned end of last year, that will increase Niger's oil exports from 20,000 b/d to 130,000 b/d.

These projects demonstrate the willingness of Chinese companies to operate in challenging regions.

In Q2 2023, China imported 1.1mn b/d of crude from West Africa, about 10% of total Chinese crude imports. In addition, the total gas reserves of Chinese projects in Africa increased from 3.4tn ft3 in 2003 to 22.5tn ft3 last year.

China has also been investing heavily into renewable energy projects in Africa, as well as in critical minerals, essential to the global energy transition.

Benefits of promoting natural gas projects in Africa

Natural gas has an important role to play in Africa during energy transition, above all in terms of providing baseload power and energy security to meet the continent’s growing energy needs.

Africa’s proven gas reserves are estimated to total more than 800 trillion ft3, making it important as a transitional energy source. Particularly, for the 600mn Africans who still lack access to electricity, using natural gas instead of biomass and charcoal can substantially reduce deforestation and power generation emissions.

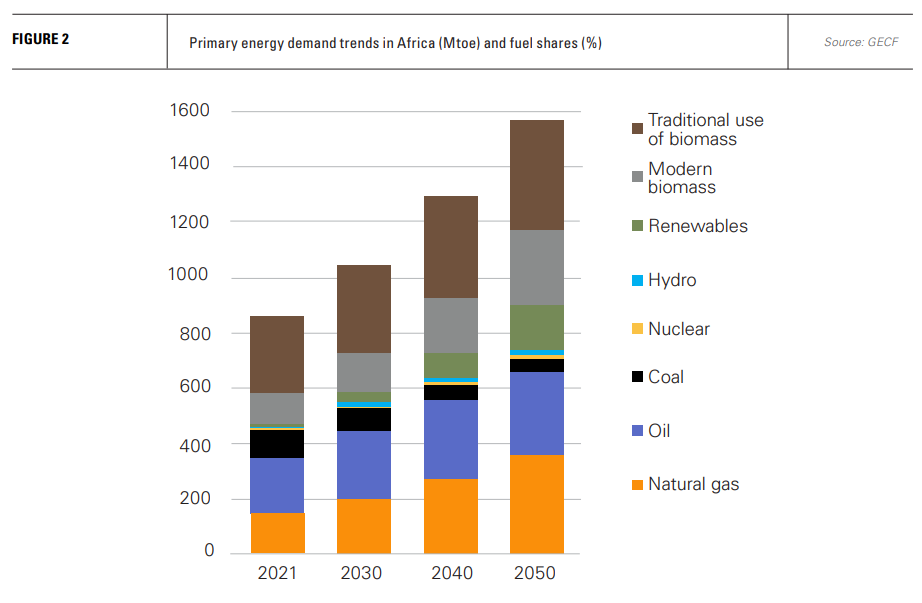

Accelerating use of natural gas can help meet Africa’s growing energy needs, improve energy security and contribute to economic growth. The Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) forecasts that between 2021 and 2050 Africa's primary energy demand is expected to increase by over 80%, with natural gas demand increasing by over 150% (see figure 2).

As Adesina said, for Africa “natural gas is not an ideological issue, it’s a pragmatic one.” Africa still offers opportunities to invest in energy, with gas providing an increasing share of Africa’s electricity.

But in order to develop these opportunities, Africa needs infrastructure, pipelines and LNG facilities. As discussed earlier, these offer huge opportunities for investment.

Adesima said “85% of AfDB’s investments in energy generation in Africa are in renewable energy.” But he added “I’m also a very pragmatic person. Africa needs to have an energy mix that allows it to have access to electricity, and energy, to have affordability for its population, and most importantly, to be able to have the security of supply for industrialisation. And so, natural gas plays a very important role in the energy mix of Africa, as it should.”

Mohamed Mansur, Wood Mackenzie VP sub-Saharan Africa, warned at Africa Energy Week 2023, said that despite investment rebounding overall, it has stalled in some African countries due to project delays. He added that “in addition to the energy transition narrative, challenges across the region persist in terms of above-ground risk, gas monetisation project lead times and fiscal attractiveness” and must be addressed.

Mansour said that Africa has great potential to use gas as a transition fuel. But often “what’s complicated with gas monetisation is that it requires long-term agreements across its entire value chain.” That can be addressed through “sustainable off-take agreements and volumes that must be identified and signed-off with attractive prices before projects can go ahead.” Nevertheless, “recent discoveries are boosting the appeal of Africa’s resources.”

This appeal is what is attracting international oil companies (IOCs) that are still providing funding for major oil and gas projects in Africa, and increasingly more in gas projects.

_f1920x300q80.jpg)