ExxonMobil plays to its strengths [NGW Magazine]

In common with many of its peers, US major ExxonMobil had a rough year, bouncing up and down on the roller-coaster market. In October it appeared to go against most other majors when it announced that it will stay with and increase investments in oil and gas production. But it was then forced to take impairments and cut spending.

Joe Biden’s election as the next US president appeared to put a check to its plans, but then it was reported that he would not impose undue restrictions on the US oil and gas sector. Then came the good news of the Covid-19 vaccines which, combined with the Opec alliance’s cautious and progressive relaxation of its oil production cuts, boosted the oil price, with Brent even above $50/b in December. Then the more infectious variant of the virus dented optimism and prices fell sharply in a few days.

Nevertheless, ExxonMobil’s share price had risen about 30% by late 2020, putting the company back ahead of US major Chevron.

Divestments and spending cuts

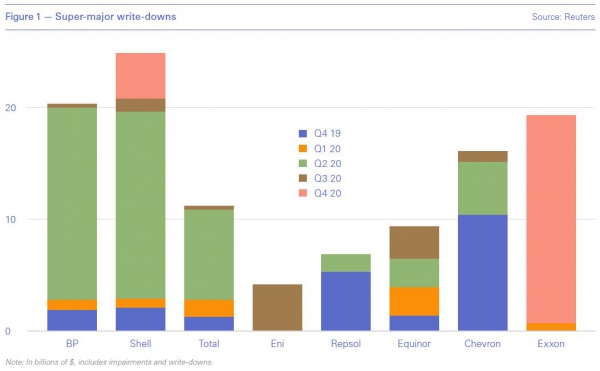

ExxonMobil announced after-tax impairments of $17-20bn in November, mostly involving less strategic, dry gas assets in the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains, Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas in the US, and in western Canada and Argentina. In effect it is writing off gas fields that the previous CEO Rex Tillerson paid a high price for ten years ago with his $35bn takeover of XTO Energy (Figure 1).

Like other majors, ExxonMobil is now focusing on areas where there is potential for growth and where oil and gas can be produced at low cost and high profits, maximising cash-flow.

These impairments, on the other hand, mean that ExxonMobil’s portfolio is now based on a much lower break-even price. So the initial pain will make it more resistant than formerly to price shocks.

It is also pursuing asset sales that potentially may reach $22bn. The company has already exited Norway and it is in the process of selling its assets in the UK and Indonesia.

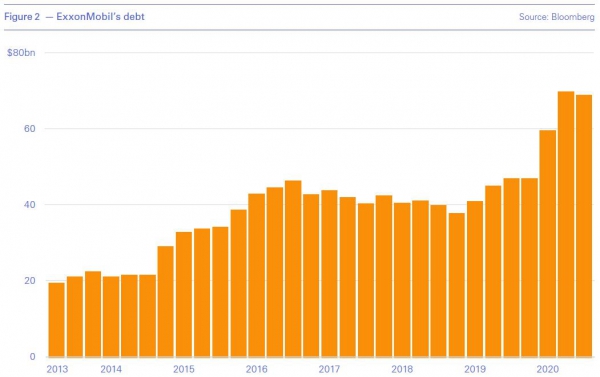

Following its third consecutive quarterly loss this year – for the first time in its history – and increasing debt (Figure 2) as a result, ExxonMobil has been forced to announce spending cuts limiting capital and exploration investments to $16-19bn in 2021 and $20-25bn/yr to 2025. That is a $10bn reduction from its pre-pandemic target. It is also targeting a 15% cut in cash operating expenses and 15% staff cuts, to be completed by end of 2021. Spending cuts in 2020 are expected to exceed 30%. But the company plans to double earnings by 2027 when its reorganisation is complete.

But, compared with its rivals, its balance sheet is still strong, with debt to equity at about 35%.

At one stage its share price was down 55% from its pre-pandemic level. It also suffered the ignominy of being removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average index in August, after 92 years on it, losing its place to a software company. Soon after – in October - it was, for a short time, overtaken as top US energy company in terms of market capitalisation by NextEra Energy, the world's largest solar and wind power generator, that ten years ago was less than a tenth of that.

Biden’s election

Statements made by Biden on his way to the presidency promise a rough ride for the oil and gas industry over the next four years. He promised to completely revamp the US energy industry, putting climate-change-driven policies at the centre of it: these include the elimination of carbon emissions from the power sector by 2035; the promotion of renewables and expansion of electric vehicles at the expense of diesel or petrol engines; and a ban on new exploration leases on federal lands. He pledged to spend $2 trillion, spread over four years, to achieve this plan. He also plans to commit to net-zero emissions by 2050 next year.

And to cap it all he announced the appointment of a formidable energy and environment team. Former governor of Michigan – and a renewable-energy advocate – Jennifer Granholm has been nominated as energy secretary and Gina McCarthy, Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator, as national climate adviser. He also nominated Michael Regan, who led the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, to head EPA. And John Kerry has been nominated as special envoy for climate change. All are well-known for their green energy credentials and the nominations confirm that he is listening to activists.

But the hope is that, as a realist and a consensus-builder, Biden will pursue his clean energy plan in a pragmatic way. If he does not and control of the senate stays with the Republicans, it is likely to meet resistance. But economic and energy security concerns are likely to play a moderating role.

ExxonMobil, having seen many challenges in its long history, is not unduly fazed by this. The company told NGW: “We congratulate president-elect Biden on his election and will work with the administration and members of Congress to support market-based policies to promote economic recovery, affordable energy development and management of environmental issues, including the important issue of climate change.”

Climate change

While announcing some measures to address climate change, ExxonMobil’s future strategy remains focused on its traditional oil and gas business and particularly on oil, for which it has a good discovery record. It has no plans to get into solar or wind energy.

ExxonMobil has long faced accusations of downplaying climate risks both in judicial and societal arenas. It has, however, supported the imposition of a carbon tax and delivering energy at lower cost and less emissions.

According to ExxonMobil, renewables on their own are not enough to solve climate change. CEO Darren Woods has said: “Today’s alternatives don’t consistently offer the energy density, scale, transportability, availability, and most importantly the affordability required to be widely accepted.”

ExxonMobil accepts that there will be a global energy transition. It also accepts that it must tackle emissions. It is also investing in research on biofuels and carbon capture technology. And in response to the need to lower emissions, it is developing better fuels, lubricants and plastics. At the same time though it also believes oil will remain a major part of global energy mix until at least 2040.

But as an executive at one ExxonMobil-investing fund said: “I know they don’t believe in transition. But the market does.” This is where the challenge continues to be, and, with ExxonMobil’s weak financial position, it will not go away.

Investor pressure is forcing change. On December 14, ExxonMobil said it would aim to cut in Scope 1 and 2 emissions – those produced by its own operations – by 15-20%/barrel by 2025, compared with 2016 levels. It also promised to publish annual emissions data for Scope 3 – those produced from the combustion of its oil and gas – but not to cut them.

Its targets also include a 40-50% reduction in methane emissions and a 35-45% reduction in flaring/barrel of oil equivalent produced by 2025, with routine flaring to be eliminated by 2030.

Announcing the new emission reduction plans, Woods said: “We respect and support society’s ambition to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and continue to advocate for policies that promote cost-effective, market-based solutions to address the risks of climate change.”

But shareholders – including the Church of England – have not reacted favourably to these plans, prompting headlines such as “ExxonMobil’s holy headache.”

ExxonMobil’s view is that meaningful decreases in global emissions will require changes in society’s energy choices coupled with the development and deployment of affordable lower-emission technologies. But, ultimately, the company does not see the returns in clean energy that it sees in oil and gas.

The world will still need oil and gas

Most credible outlooks and forecasts show that in one or two decades’ time, the world will still need significant quantities of oil and gas. This is what ExxonMobil is banking on.

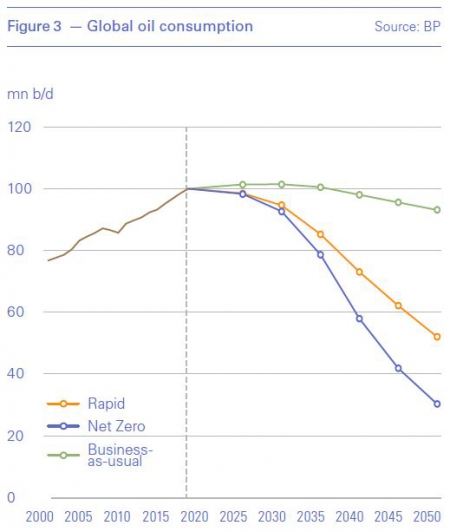

BP’s Energy Outlook 2020 is one such example. It shows oil demand peaking in the 2020s, but thereafter the rate of decline depends on the scenario considered (Figure 3). In business-as-usual (BAU) oil demand sees only a small reduction by 2050, but the drop in two other scenarios, Rapid and Net Zero. is more precipitous, down to about 50mn b/d and 40mn b/d respectively: a little less than half the pre-covid level.

But future growth in global energy demand is expected to come almost entirely from emerging economies, where rapid transition and net-zero policies may be more difficult to implement. In addition, apart from European majors, US majors and national oil companies (NOCs) are mostly carrying on with BAU. Under such circumstances, future growth in oil demand may not yet be over.

Renewables will be the fastest growing global energy source. But, depending on what happens in Asia, demand for fossil fuels is expected to remain strong for some time – somewhere between the BAU and Rapid scenarios.

The IEA states that only its Sustainable Development scenario (SDS) can produce a decisive break – and only then in the unlikely event of all governments worldwide not only building sustainability into their recovery strategies but also fully applying them.

And even in that rosy scenario the oil and gas industry will still require investment of about $425bn/yr to meet demand as supply declines faster than demand.

Opec forecasts that oil demand will carry on increasing, to reach 109.3mn b/d by 2040 and start declining slowly thereafter, driven by demand in non-OECD countries.

ExxonMobil’s gamble on oil and gas may turn out not be such a gamble after all. This raises the question: has it got it right, with a reasonable chance that it may end up being the biggest privately owned international oil company (IOC) when the music stops?

Turning to oil

While competitors, such as the European IOCs, are shifting from fossil fuels to clean energy, ExxonMobil plans to boost oil and gas production by a third over the next four years.

It believes that such a strategy will succeed as oil demand and prices recover – as the world economy emerges from the ravages of Covid-19 – while global oil supply growth slows because of under-investment upstream.

This is a view shared by analysts who expect global oil demand to recover significantly in 2021. In a recent Financial Times live event Goldman Sachs said it expects a rapid recovery, with oil demand rising to 102.5mn b/d and Brent reaching $65/b on supply constraints.

In November ExxonMobil abandoned plans to sell its oil and gas assets in Australia’s Bass Strait. The company now sees these as being more valuable to its portfolio. In December it bid for stakes in ONGC’s oil and gas fields in India.

In Guyana it has made 18 world class discoveries at the Stabroek block, with its total oil resource estimate now exceeding 9bn barrels oil equivalent (boe) – a great exploration success. Production from the Liza Destiny floating production, storage and offtake vessel (Figure 4) has just reached full capacity of 120,000 b/d. ExxonMobil and its partners plan five projects in Guyana expected to produce more than 750,000 b/d by 2025.

It has also found oil in Suriname, in the same basin as Guyana.

At the same time, as part of its cost-cutting drive, ExxonMobil is slowing down its investments in LNG plants. Golden Pass LNG in Texas is likely to be delayed by a year to 2025, as will expansion of its LNG project in Papua New Guinea. In addition, Rovuma LNG in Mozambique is already late. ExxonMobil may be taking advantage of a view that over this period LNG demand growth may not justify rushing into investing in new supplies, helping conserve cash-flow.

New priorities

Following the announcement of divestments and spending cuts and completion of its review of its forward business plans end of November, ExxonMobil said that in the near-term it will prioritise spending on high-value assets in Guyana, the Permian, Brazil and chemicals performance products, “while working to maintain a reliable dividend.”

ExxonMobil told NGW: “Our strategy is based on fundamentals, which are outlined in the Darren Woods email… We continue to invest in industry-advantaged projects, including Guyana and the Permian. Our portfolio of opportunities is the best it has been in more than 20 years.”

Woods made it clear that oil and gas remain central to the company. He said that fossil fuels will still meet roughly half of global energy demand by 2040 and will often provide the most cost-effective pathway to development in poor countries, especially in Africa and Asia, through affordable energy.

“This is a compelling investment case for the industry and our company and is foundational to our long-term strategies and plans,” he said.

ExxonMobil believes in oil’s future, even as many of its peers believe that it is time to trim their sails as the storm brews and to move away from oil and gas.