Europe will sustain its appetite for LNG in 2020 [LNG Condensed]

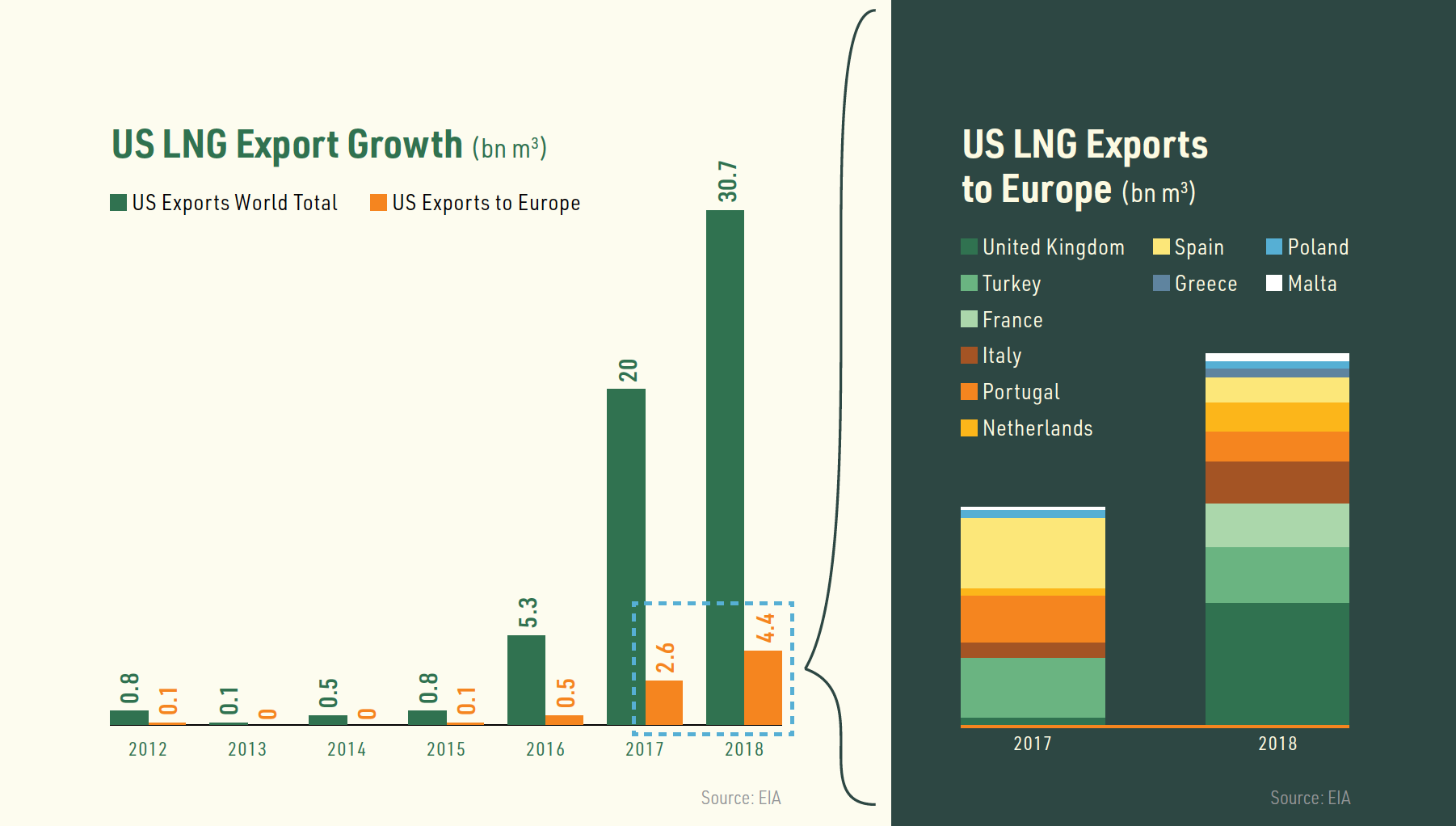

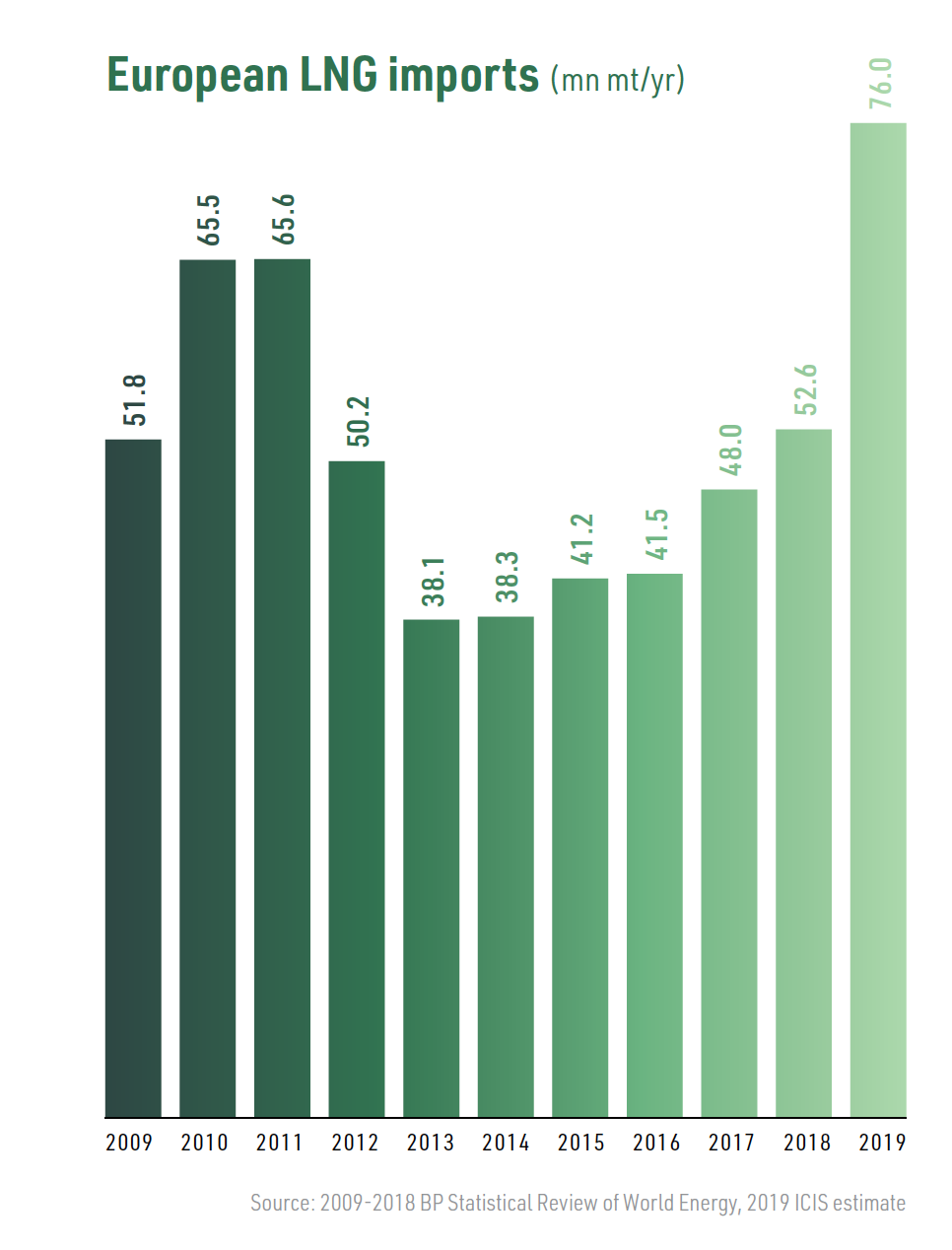

Europe’s growing appetite for LNG has been driven by low prices created in turn by the volume of new LNG production coming to market in the last few years. In particular, US LNG exports were up 37% alone in the first half of 2019 with capacity rising to 55.8bn m3/yr (5.4bn ft³/d), according to US Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. And there is more, much more to come. By the end of this year, the EIA sees total US LNG export capacity rising to 92bn m3/yr.

The impact on spot prices has been substantial. Whereas a seasonal upturn in winter pricing is the norm, spot prices for LNG have instead fallen over winter 2019/2020. In January, Asian spot prices, represented by the Japan-Korea Marker (JKM), hit some of their lowest-ever levels dropping below $4/mn Btu -- unheard of for this time of year.

This comes despite a rapid and sustained rise in Chinese LNG imports, which jumped from 27bn m3 in 2015 to 73.5bn m3 in 2018 and are estimated to have risen by a further 20% last year. The surge in supply has more than accounted for four years of rapid Chinese demand growth, the pace of which is now slowing and been combined with a relatively mild northeast Asian winter. This dampens demand in the world’s three largest national LNG markets – Japan, China and South Korea.

China, in addition, has been busy building gas storage capacity in an attempt to avert the gas shortages of 2017/18. This improved ability to manage seasonal demand flows back into reduced price volatility in the Winter spot market.

LNG demand is seasonal and a mild winter has knock-on effects as stocks are not reduced as much as might have been the case in colder weather. LNG importers in fact entered the 2019/2020 with inventories already at high levels. This, and the low level of drawdown amidst ample supplies, means less re-stocking will be required in the spring and Summer, rolling forward the period of low pricing.

A market report issued by S&P Global Platts in January predicted even lower prices as supply continues to outstrip consumption and the market enters the lower-demand summer period. The report commented: "JKM is expected to fall close to $3/mn Btu in the months ahead, which would leave the potential for sub-$3/mn Btu assessments on select days this summer.”

Demand stimulus

The low price of LNG has pushed down gas prices across Europe’s gas hubs, making gas a more competitive fuel for power generation. Higher gas use represents to some extent price-driven flexible demand, but there also important structural issues at play, which bode well both for European gas demand and more particularly for the volume of European gas imports.

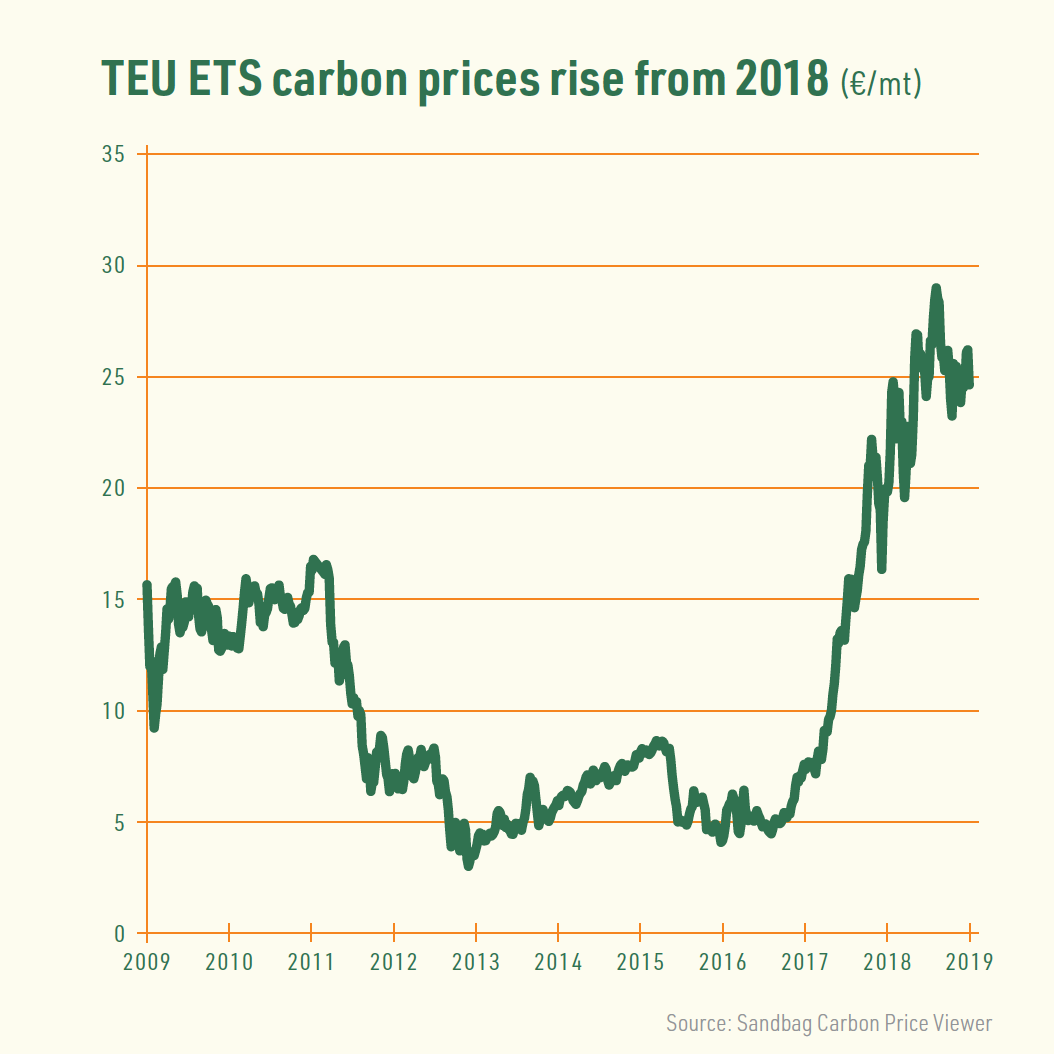

Low gas prices have been accompanied by a sharp rise in carbon allowance prices under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). These rose sharply in 2018 from below €10/mt ($11.1/mt) to close to €30/mt in 2019 as a result of reforms to the way in which the ETS operates. Broadly, the supply of carbon allowances in the next phase of the ETS will be reduced more sharply, if a large surplus persists.

Higher carbon prices hit coal-fired generation margins, as a hard coal plant emits roughly twice the carbon emissions of a combined-cycle gas turbine. The combination of low fuel costs and a high carbon price swings the profit pendulum in gas’ favour.

Although opinions differ on how carbon prices will evolve, they certainly seem set to remain substantially higher over the next five years than in the period from 2008 to 2018.

Goodbye coal

At the same time, coal-fired generation in many European countries is being phased out, removing one of gas’ key competitors altogether. The UK, in particular, has seen a sharp drop in coal-fired generation and expects to end it out altogether by 2025.

The latest country -- and the most significant in terms of existing European coal-fired capacity -- to join the rush to the exit is Germany.

A multi-stakeholder agreement reached in January by the country’s Coal Commission recommends that coal-fired generating capacity is cut by 12 GW in 2022 to 31 GW, falling further to 17 GW by 2030 and zero by 2038. At the same time, the country’s remaining six nuclear reactors are set for closure in 2022 and 2023 (see Country Focus, Germany – phasing LNG in -- this edition of LNG Condensed).

There appears to be no road back for coal-fired generation in Europe as one of the first acts of the new European Commission has been to promulgate even more ambitious climate change goals aiming to make the bloc a net zero carbon emitter by 2050.

There are also no power sector carbon capture and storage projects operating in the EU and policy on CCS has moved further away from seeing the technology as a means of coal plant emissions mitigation to focus instead on industrial emissions.

Domestic production

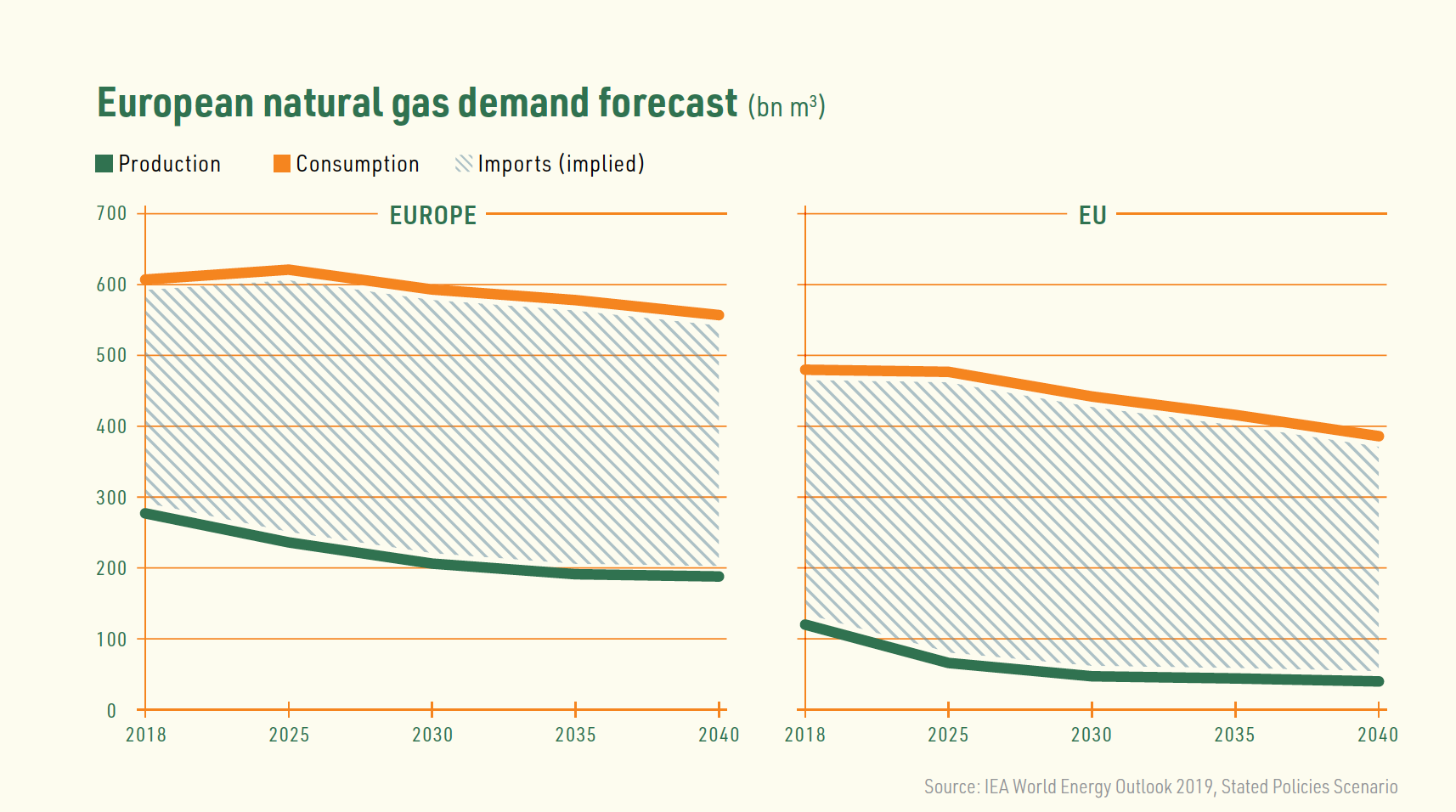

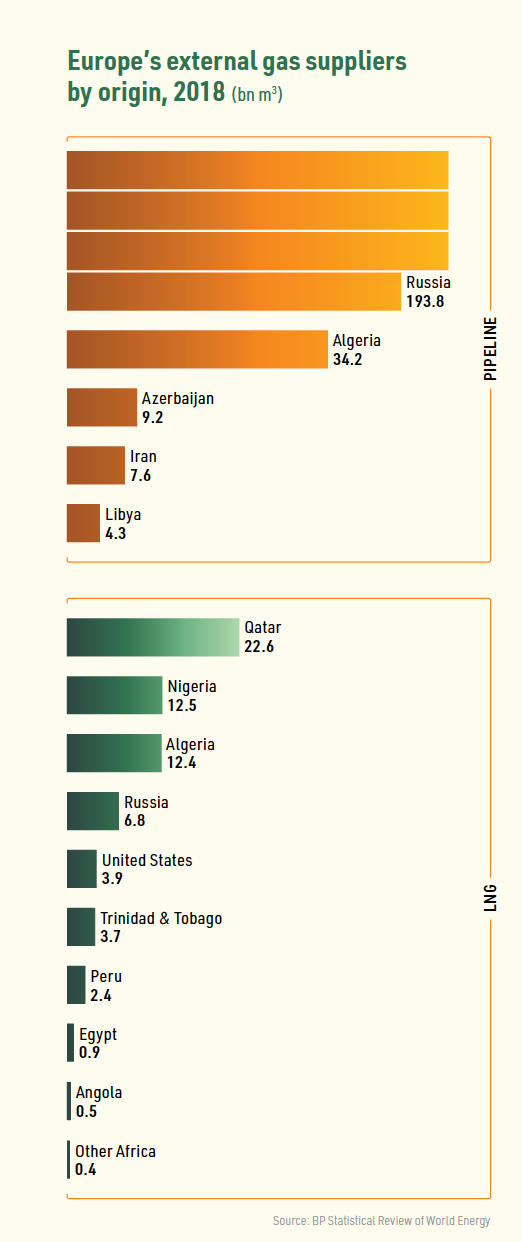

This suggests Europe has little choice but to turn to natural gas and renewables. If there is some uncertainty regarding the overall level of European gas demand, there is much less with respect to the need for increased gas imports. This is because domestic EU gas production continues to fall and the drop has been hastened by developments at the giant Groningen gas field in the Netherlands.

Domestic EU gas production decreased 8.8% in 2018 to 109.1bn m3, the eighth consecutive year of decline. Last autumn, the Dutch government announced that output from the Groningen field would be capped at just 11.8bn m3 in the 2019/2020 gas year, down 40% from 2018/19 and that production would halt completely by mid-2022, eight years earlier than previously planned. This will create a big hole in EU gas supply which will need to be filled by imports.

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) forecast for European gas demand is that it will rise from 607bn m3 in 2018 to 621bn m3 in 2025. Within that, EU gas demand is expected to fall from 480bn m3 to 477bn m3. This is based on the IEA’s Stated Policy Scenario prior to the announcement of the agreement on Germany’s coal phase out policy.

However, over the same period, European gas production is expected to fall 41bn m3 and EU gas production almost halves, plunging 54bn m3. This implies a net rise in European gas imports of 55bn m3 by 2025, of which the EU will account for 51bn m3.

Increased flexibility

A further structural change is Europe’s ability to absorb LNG, which has grown steadily over time as European gas hubs have become more liquid and the EU has developed the regulatory side of the bloc’s gas markets. It has been a long road in terms of the erosion of oil indexation and increased spot buying in preference to inflexible take-or-pay contracts.

And there is still more road to travel, but deeper, more liquid hubs, as evidenced by the growth of the Dutch TTF, served by more open-market regulation providing third-party access to infrastructure, has created the means for greater competition between pipeline and LNG supplies.

Moreover, Europe has been notable for its excess regasification capacity and thus flexibility to absorb additional volumes of LNG, if the price is right – as it currently is.

Regasification capacity worldwide continues to increase steadily, reaching 824mn mt/yr by February 2019. According to IGU data, based on terminals under construction, global regas capacity will push through 900mn mt/yr this year, reaching about 950mn mt/yr in 2022.

Much of this capacity will go unused – countries heavily dependent on LNG need to keep surplus capacity to deal with seasonal variations in demand, and in some markets LNG demand is falling as a result of increased domestic gas output or competition from pipeline supplies, leaving LNG terminals effectively stranded.

But while barriers to LNG intake may remain within EU gas markets, it is hard to argue that regas capacity is a significant constraint, particularly in northern Europe and on the Iberian Peninsula.

In 2018, which saw a jump in European LNG imports of 9.6%, the utilisation rate for UK regas capacity was still only 15%, France 40%, the Netherlands 29% and Belgium 40%. Spain and Portugal recorded utilisation rates of 25% and 51% respectively. Utilisation will undoubtably have been higher last year, but Europe still retains significant spare LNG import capacity heading into 2020.

Pipeline competition

Pipeline competition

While renewable energy capacity continues to expand in Europe, with a particular push into offshore wind, the biggest short-term threat to European LNG demand is pipeline gas, but here Europe’s dependence on a few large external suppliers has played to LNG’s advantage. Particularly in Eastern Europe, the value LNG brings in terms of the diversification of gas supplies and price competition have favoured its adoption, even if it is not necessarily the cheapest option.

The last minute nature of the resolution of the Russia-Ukraine gas dispute, which resulted in an eleventh hour agreement on December 31, securing Russian gas supplies through Ukraine to Europe for five years, will have done little to instil confidence in Russian pipeline supplies for the first-half of 2020, adding to LNG’s current attractiveness. In addition, US sanctions on activities surrounding the construction of the controversial 55bn m3 Nord Stream 2 pipeline also add uncertainty.

Conversely, however, the Russia-Ukraine deal alongside the likely eventual completion of Nord Stream 2 means Russia will have significant excess export capacity to Europe. In addition, Russian gas giant Gazprom is making progress on its TurkStream pipeline across the Black Sea, which was formally launched in January.

The Azeri-fed Trans-Anatolian Pipeline was completed at the end of 2019, while its extension to Italy -- the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline – should be finished later this year. Even Norway is getting in on the act, building, with Polish and Danish support, Baltic Pipe, which will bring Norwegian gas into Poland, albeit primarily with the intention of displacing Russian pipeline gas rather than LNG.

Yet despite the growth in pipeline import capacity – and the feeling that some of these projects emanate from another era -- LNG terminals are still being planned and built, most notably the likelihood of two in Germany, the country’s first, despite Germany being the landing point of the Nord Stream pipelines.

Pipeline politics will continue to favour LNG as European countries remain unwilling to extend their dependence on Russian gas as their own domestic gas supplies dwindle.

Given the expansion in pipeline capacity to Europe and the rise in LNG imports over 2018 and 2019, competition between pipeline gas and LNG is likely to be fierce – the key components of that competition being not just price but flexibility. Given the expected lower-for-longer outlook for LNG prices on the international market and political preferences for supply source flexibility and diversification, LNG is better positioned than ever before to compete.

One thing at least seems certain: Europe will not lack gas, while its ability and desire to consume it will remain high, owing to low prices, coal and nuclear phase outs and higher carbon prices.