Europe tackles methane emissions [NGW Magazine]

The natural gas industry has come under fire after revelations of increased flaring and large leaks undermine its claims to be a clean transition fuel. But most of the emissions occur upstream, outside Europe. The European Commission (EC) is working on how to address the international angle in its methane emissions strategy, which should be revealed in September.

“The EC presented its vision of a European Green Deal for the European Union and its citizens on 11 December 2019, which includes addressing the issue of energy-related methane emissions. The 2018 Energy Union Governance Regulation calls on the EC to deliver a strategic plan for methane and the energy sector could significantly contribute to it,” said a spokesperson.

Comments on a proposed roadmap were due by August 5 and are published on the EC website. As well as setting standards for monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) and leak detection, the strategy is likely to include only soft measures for voluntary collaboration at an international level rather than a mandatory methane supply index, which will fall short of what is required and technically feasible, says Poppy Kalesi from the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

EDF is working on a study of 16 different options for a methane emission import standard, such as including methane in the emissions trading scheme (ETS) and a fee on imports, which should be released in December. Options include price-oriented mechanisms such as penalties; a border adjustment tax or amendment to gas taxes based on climate effect; regulation such as a procurement standard; or a volume-oriented mechanism such as cap and trade or other tradeable quota system.

A procurement standard could incentivise a reduction in methane emissions intensity of imported gas in the form of tax benefits or penalties for the buyers for non-compliant purchases. The EC prefers some sort of market-based certification scheme, says Kalesi, but other than for aviation and shipping it is not yet feasible for energy-industry methane emissions to be covered by the existing European emissions trading scheme (ETS).

The International Standards Authority is working on an LNG label, initially covering emissions during liquefaction and addressing gas production and shipping subsequently. A working group will meet in September to discuss how to classify the LNG plant according to its carbon footprint under a low carbon LNG certificate.

An industry group – including the biggest European producers BP, Eni, Equinor, Repsol, Shell, Total and Wintershall Dea together with EDF, the Florence School of Regulation and the Rocky Mountain Institute – recommends a methane intensity-based performance standard of less than 0.20% for the upstream supply chain from 2025.

This is slightly more stringent than voluntary measures such as the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI)’s initial carbon intensity target, of 20-21 kg CO2e/kg barrels of oil equivalent by 2025, or 0.25% methane intensity. OGCI includes many of the companies listed above, such as Total, which has set an even more ambitious methane intensity target of 0.1% for its operated upstream gas facilities.

Another proposal submitted in comments by the Austrian national regulator E-Control is to create a mandatory framework for transmission system operators based on a threshhold set by the best available technology as predefined by a technical body.

European companies have already taken voluntary steps to reduce their own emissions, aligned with the Methane Guiding Principles Best Practice Guides and the US Natural Gas STAR Program Recommended Technologies to Reduce Methane Emissions. More than 20 European companies and 14 supporting organisations have signed on to the Methane Guiding Principles, a commitment to manage methane emissions along the gas value chain. Gas Infrastructure Europe and Marcogaz have continued to raise awareness of this topic and identify concrete action points, create guidelines to help companies set reduction targets, make methane policy recommendations, reconcile top-down and bottom-up best practises for measuring, reporting and verification and devise a reporting template.

OGCI’s Climate Investments fund has an open call for methane reduction projects that closes September 14. Power generation companies are already embarking on goals to reach climate neutrality by decarbonising their gas-fired power plants and storage facilities. The German utility Uniper has partnered with General Electric to develop technology options for decarbonisation involving potential upgrades and using more hydrogen.

Made to measure

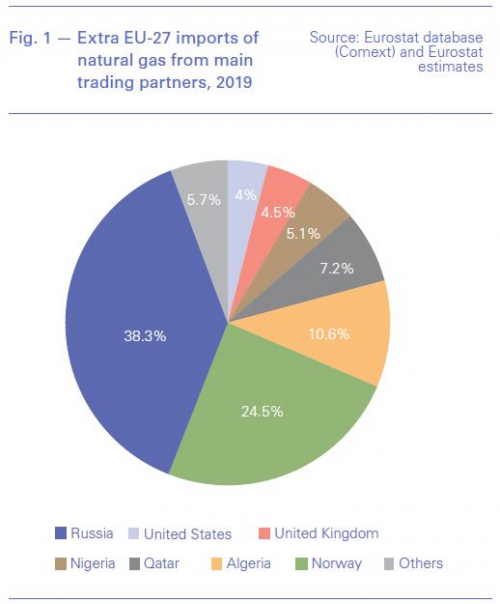

Less than a quarter of the methane emissions from natural gas consumed in the EU occurs within its borders, according to Carbon Limits, a consultancy. Around 80% of the EU’s natural gas is imported, mainly from Russia, Norway, Algeria, Qatar and Nigeria. Until now methane emissions from flaring, venting and leaks have been mostly self-reported and/or estimated. Emissions intensity varies widely and until recently it was hard to tell whether companies were accurately reporting emissions, especially during large leaks or unplanned venting. But that is about to change.

Recent developments in satellite technology combined with enhanced data interpretation techniques have paved the way for the creation of a more robust international framework for the detection, monitoring, reporting and verification of methane emissions across the full value chain of natural gas. This will make it easier to account for upstream emissions from the natural gas supply chain, not just for more visible flaring. Producers will face increased scrutiny for accidental leaks and intentional venting, that will present a competitive advantage for early adopters of emission cutting upgrades and penalise persistent heavy emitters.

OGCI will spend nearly $1mn on a publicly available online tool to map gas flaring data, working with the Payne Institute for Public Policy at Colorado School of Mines as part of the Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR) led by the World Bank. It will use the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) satellite and will be available in 2022.

A coalition of non-profits and technology companies has developed a monitoring solution using artificial intelligence and satellite image processing that received high profile attention thanks to the patronage of the former US vice president Al Gore. The first version of ‘Climate Trace’ (another acronym, standing for Tracking Real-time Atmospheric Carbon Emissions) could be released as early as next summer. And there are many similar initiatives, such as Canada’s GHGSat which recently assembled its third satellite, part of a programme to put 10 greenhouse gas emissions monitoring satellites into orbit within the next two years.

French company Karryos, based on Sentinel-5P images from the European Union’s Copernicus network, estimates there almost 1bn metric tons of CO2e near-term mitigation potential.

“Eliminating methane ‘super-emitters’ is the low-hanging fruit of climate action, but market participants need both greater actionable information and regulatory certainty,” Karryos said in comments to the EC consultation.

While many energy companies pointed out in their comments to the consultation that the agricultural sector is a considerable contributor to methane emissions, “It’s not a question of either, it’s a question of and,” said Stephanie Saunier from Carbon Limits. Aside from the inevitability of legislation next year, when the EU will issue its gas market reform, cutting methane emissions makes good business sense.

Almost 300bn m³ of gas or 7% of consumption is wasted globally by flaring, venting and leaks, leading to a revenue potential loss of $34bn, according to consultants Capterio. But perhaps even more important is the reputational damage that may be wrought by ignoring growing pressure to come clean.

Companies such as Shell and Abu Dhabi state producer Adnoc are already delivering cargoes to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan offset with carbon emission reductions. And Pavilion Energy of Singapore issued a request for proposals for long-term LNG including a commitment to jointly develop an emissions quantification and reporting methodology.

Even national oil companies from traditionally climate-ambivalent countries such as in the former Soviet Union and Africa are starting to wake up to this new reality. The public image and therefore the future of the natural gas sector in the coming decades, as well as the growing blue hydrogen industry, will depend very much on how it tackles the methane emissions problem.

|

EU Prepares Emissions Strategy The European Commission is due to come up with ways to limit anthropogenic methane emissions, less than a fifth of which come from energy. Agriculture and waste are each bigger contributors. The Green Deal and the Paris Agreement are both pushing the EU towards climate-neutrality, where any remaining greenhouse gas emissions are offset by carbon abatement such as carbon sinks. Some estimates show that external carbon or methane emissions associated with EU natural gas consumption are between three and eight times the number of emissions occurring within the EU. Further, external emissions are not evenly distributed with the bulk of the emissions coming from a very small proportion. So eliminating these would be relatively big gains. Within the EU, infrastructure operators are regulated and do not own the molecules that are leaking from import terminals and pipelines. This suggests that national regulators will have to find a find a way of incorporating leak detection and repair activity as part of their allowed costs. The first problem facing the EU is to set emissions measurement standards: there is likely to be an incentive to under-report. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has a three-tier reporting framework for methane emissions, which might form the basis of such a system, although there is no consistency between member states. Tier 1 is the crudest, involving simple estimates while Tier 3 requires individual measurements. Very few countries are in this group. The EU will probably work with other organisations such as the World Bank, which regularly reports on flaring based on satellite imaging, and has a Zero Routine Flaring initiative. On the ground, a harmonised policy for encouraging biogas could encourage technology that reduces methane emissions while providing renewable energy, converting waste streams into cash for farmers. The EU could offer technical assistance on methane regulatory frameworks and monitoring, reporting and verification capacity but it can also learn from countries with methane-reduction targets. Other big exporters, such as Russia, could also become involved, if they want to keep selling their gas. But not all Gazprom’s exports flow through EU pipelines: some also go through Belarus or Ukraine. The EU could also work together with other big importers such as South Korea and Japan to bring pressure to bear on exporters to implement methane reporting and verification standards, which in turn would make emissions reduction technologies more attractive investments. -NGW |