EU Green Deal will shrink oil and gas imports dramatically [GasTransitions]

The EU Green Deal will have profound geopolitical consequences, write researchers from Bruegel and the European Council on Foreign Relations in a new report. “The Green Deal will truly shape foreign policy,” says Bruegel Research Fellow and co-author Simone Tagliapietra in an interview with Gas Transitions.

The geopolitical impacts of the energy transition are likely to be felt first of all in relation to Europe. The EU’s Green Deal currently represents the world’s most ambitious pathway away from fossil fuels, although the US, China, Japan and other countries are on the same track.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

In a new report, “The Geopolitics of the Green Deal”, researchers from the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) and think-tank Bruegel in Brussels, point out that the EU’s climate plan “will have profound geopolitical repercussions”, which have not had much attention yet. The EU “needs to wake up to the consequences abroad of its domestic decisions,” they write. “It should prepare to help manage the geopolitical aspects of the European Green Deal.”

According to co-author Simone Tagliapietra, Energy & Climate Fellow at Bruegel, “the EU Green Deal will truly shape EU foreign policy. It is one of the key items defining it.” He explains that the researchers at Bruegel felt there was “an urgent need to understand how energy currently impacts foreign relations, how this will change and how it needs to be managed. That’s why we reached out to our colleagues at the ECFR to look into this. I think it’s quite a novel study.”

The report is certainly timely. “EU Ministers of Foreign Affairs have just taken up the subject,” notes Tagliapietra. Coincidentally, the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies also published a special issue of the Oxford Energy Forum on “The Geopolitics of Energy” in February, which looks at the topic from a global perspective.

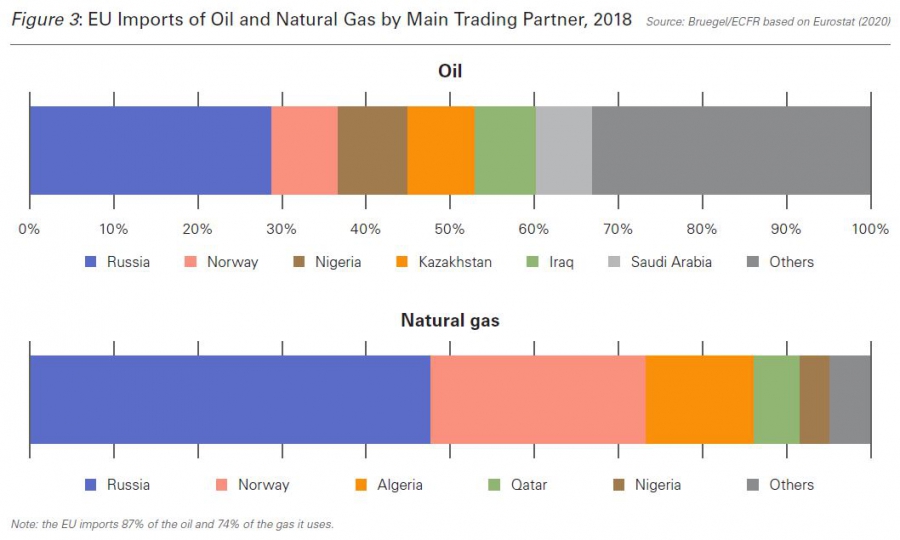

The Green Deal report gives five reasons why the Green Deal is key to EU foreign policy. First, it observes that the EU imported more than €320 billion worth of energy products in 2019. “A massive reduction in this flow will restructure EU relationships with key energy suppliers. Countries including Russia, Algeria and Norway will ultimately be deprived of their main export market. Inevitably, Europe’s exit from fossil-fuel dependency will adversely affect a number of regional partners, and may even destabilise them economically and politically.”

Secondly, Europe accounts for around 20% of global crude oil imports. “The fall in oil demand resulting from Europe’s transition to renewables will impact the global oil market by depressing prices and reducing the income of the main exporters, even if they do not trade much with the EU.”

Third, “a greener Europe will be more dependent on imports of products and raw materials that serve as inputs for clean energy and clean technologies. For example, rare-earth elements, of which China is the largest producer, are essential for battery production. Moreover, Europe could remain a major net importer of energy but that energy will need to be green, such as green hydrogen produced in sun-rich parts of the world.”

Fourth, “the Green Deal will impact Europe’s international competitiveness. If European firms take on regulation-related costs that their foreign competitors do not bear, they will become less competitive both domestically and abroad. And if the EU attempts to limit this loss and avoid carbon leakage by imposing tariffs on carbon-rich imports, it risks being accused of distorting international trade.”

Fifth, “climate change is a global problem. A transition away from carbon that would only focus on Europe would not do much to mitigate global warming, as Europe represents less than 10 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions. Worse, if the Green Deal simply displaces Europe’s greenhouse gas emissions to its trading partners, it will have no impact at all on climate change. If only for this reason, the EU is likely to push very hard for ambitious enforceable multilateral agreements on containing global warming and will subordinate some of its other objectives to this overriding priority.”

The authors note that “already, the European Commission has recognised that it will either need to export its standards or create a [carbon] border adjustment (CBA) mechanism to maintain European competitiveness and prevent carbon leakage.”

Radical change

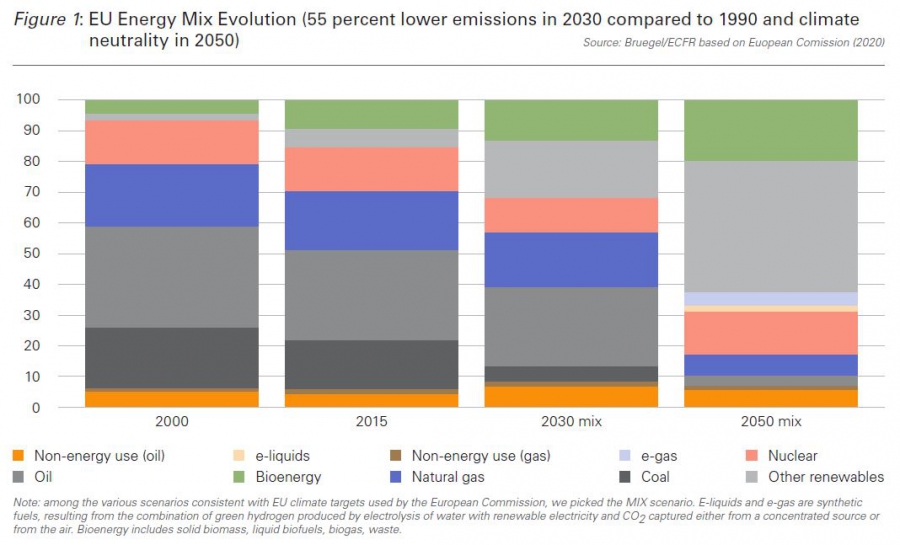

The Green Deal report notes that currently “almost three-quarters of the EU energy system relies on fossil fuels. Oil dominates the EU energy mix (with a share of 34.8 percent), followed by natural gas (23.8 percent) and coal (13.6 percent). Renewables are growing in share but their role remains limited (13.9 percent), similarly to nuclear (12.6 percent) (Eurostat, 2019).

Most of the change for oil and gas will happen between 2030 and 2050. Within this timeframe, oil is expected to be almost entirely phased-out, while natural gas would contribute just a tenth of EU energy in 2050.”

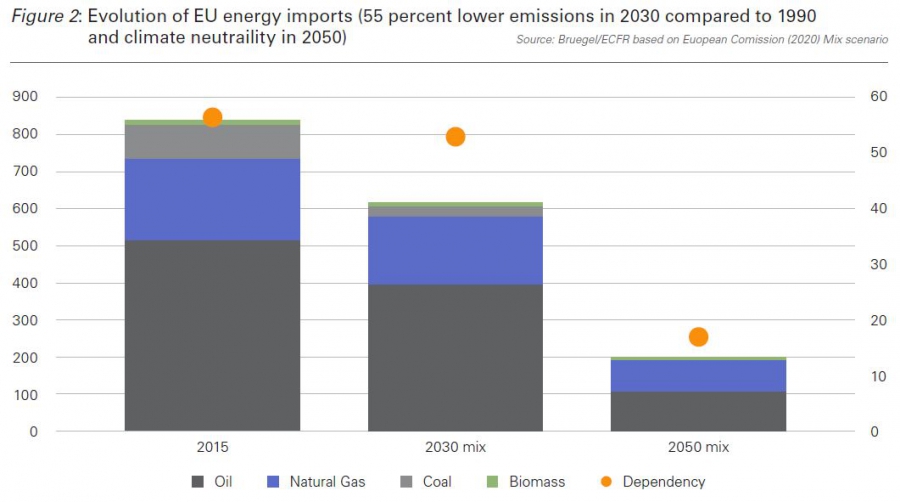

Depending on which scenario will play out, oil and natural gas imports are expected to shrink dramatically after 2030, with oil imports down 78-79 percent and natural gas imports down 58-67 percent compared to 2015:

Over the next decade, the EU-Russia oil and gas trade will not be substantially impacted, as Europe would only marginally reduce its oil and gas imports by 2030 even in a 55% emissions reduction scenario (see section 2), but the situation will radically change after 2030 when Europe is expected to substantially reduce its oil and gas imports.

Tagliapietra observes that for gas, until 2030, Russia and other exporters to Europe might well benefit from the energy transition, thanks to coal-to-gas switching. “After 2030, however, Russia will feel the pain,” he says. “This will be caused not just by lower oil and gas exports, but also by a reduction in the export of carbon-intensive goods, such as steel, aluminium and ammonia, which are likely to be hit by carbon border taxes.”

There are opportunities for Russia to benefit from these developments, according to the Green Deal report. “Russia’s inefficient energy system implies many opportunities to reduce carbon intensity in its economy. There is ample scope for European cooperation with Russia on increasing the use of renewables, reducing methane leakage and boosting energy efficiency.”

“Russia will have to make up its mind how to respond,” says Tagliapietra. “They could invest in renewables and green hydrogen and diversify their economy.”

How the drop in imports will impact market shares in natural gas is not clear, but Tagliapietra expects that “competitiveness will become more important. Russian gas is probably the most competitive. LNG suppliers will have to find other markets.” He does not think that any Carbon Border Adjustment will treat LNG differently from natural gas.

From the point of view of Europe, its long-felt dependence on Russian natural gas “will become a thing of the past.” Already, in recent years, the security of supply for natural gas imports into the EU has been greatly strengthened, notes the report. By further “reducing the continent’s gas import requirements between 2030 and 2050, the European Green Deal will definitively solve Europe’s oil and gas security concerns – and will also reduce Europe’s oil and gas import bill.”

There will also be an impact on gas infrastructure, notes Tagliapietra. “There is no need to invest in new natural gas infrastructure in Europe anymore. Some of the existing infrastructure, if it can’t be used for hydrogen or renewable gases, will become stranded. That’s inevitable in a transition.”

New risks

However, the European Green Deal will also create new energy security risks for Europe, according to the report, “most notably from the import of the minerals and metals needed for the manufacturing of solar panels, wind turbines, li-ion batteries, fuel cells and electric vehicles. These minerals and metals have particular properties and few to no substitutes.”

Green hydrogen will also create import dependency, as Europe will increasingly import hydrogen from Africa and the Middle East, says Tagliapietra. He believes that it will be possible for Europe to develop projects in those regions that will benefit both exporters and importers, if they are managed well and if Europe is prepared to invest.

“It is true that people in these countries need energy themselves first of all. But there is so much land availability and so much solar irradiance in the deserts that it will be possible to create export industries that the population will benefit from.” He cites a recent deal between Germany and Morocco to develop Africa’s first industrial plant for green hydrogen as an example.

The EU should also be prepared to subsidize green hydrogen projects abroad, says Tagliapietra. But not “blue” hydrogen projects, based on natural gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS). “Blue hydrogen will lead to lock-in of fossil fuels. With renewable energy having become so cheap, green hydrogen is the technology of the future.”

One of the most complex geopolitical issues that the European Green Deal will have to deal with is the notion of a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). It is almost inevitable that the EU will have to introduce this, if it is to make the Green Deal a success, but it is a proposal that generates a lot of concern among Europe’s main trading partners, such as the US. “A carbon tariff could dramatically impact US exports of coal, natural gas and many manufactured products,” notes the report.

“Requiring compliance with strict environmental regulations as a condition to access the EU market will be strong encouragement to go green for all countries,” the researchers write hopefully. Tagliapietra hopes that for the EU it will be possible “to have a different conversation with the Biden administration” than it had with Donald Trump.