EU 2040 emissions targets: what could they mean for LNG? [Gas in Transition]

Europe’s LNG imports jumped massively last year, reaching 170.2bn m3, up from 107.5bn m3 in 2021, according to data from the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2023.

The upward leap is all the more significant considering that Europe’s LNG imports had already increased substantially in 2019-2021. In this period, they averaged 114.4bn m3/yr, in comparison with 64.1bn m3 in the preceding three years. Coal and nuclear phase-outs more than outweighed the demand hit of COVID-19, which was much more pronounced in the liquid fuels sector.

The upward leap is all the more significant considering that Europe’s LNG imports had already increased substantially in 2019-2021. In this period, they averaged 114.4bn m3/yr, in comparison with 64.1bn m3 in the preceding three years. Coal and nuclear phase-outs more than outweighed the demand hit of COVID-19, which was much more pronounced in the liquid fuels sector.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

This year, despite buoyant stocks at the end of the heating season, Europe is expected to continue importing LNG at high levels, using its newly-expanded regasification capacity to offset the huge loss of Russian gas imports by pipeline caused by sanctions and the war in Ukraine.

However, Europe’s gas buyers face a profound dilemma with regard to the trajectory of gas demand. The EU has turned to an accelerated energy transition as a means of resolving both its dependence on Russian gas and fossil fuels in general.

The ambivalence and uncertainty this has created has been demonstrated by the relative lack of long-term agreements for new LNG supply entered into by European buyers, as opposed to Asian buyers and portfolio players. Investment needed to increase the global supply of LNG has not been forthcoming from the hottest market in town, one which, in the absence of the energy transition, would be expected to be driving forward new investment at a substantial rate.

2040 target suggests the caution is well founded.

Under the 2021 European Climate Law a new body was founded to provide independent scientific advice to the EU institutions and member states on climate science. It was also tasked specifically with providing an interim target for the region’s GHG emissions reductions for 2040.

The organisation, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC), delivered its first conclusions in June and, if the EU’s 2030 emissions target looks challenging, the period 2030-2040 will require an even greater step up in ambition..png)

ESACBB recommends that the EU’s GHG emissions budget should stay within a limit of 11-14 Gt CO2e between 2030 and 2050 to ensure the EU’s contribution to climate change mitigation is on a 1.5°C pathway with no or only a limited overshoot. To do so, emissions reductions of between 90-95% by 2040 are necessary relative to 1990 (see table 1).

This compares with the current target of at least 55% by 2030. The report says this target enables achievement of the recommended 2040 target and carbon neutrality by 2050, but if the 2030 target was increased up to 70% or more “it would considerably decrease the EU’s cumulative emissions until 2050, and thus the fairness of the EU’s contribution to global mitigation.”

The implication is not only that the 2040 target must be high, but that a case for tightening the existing 2030 target also exists.

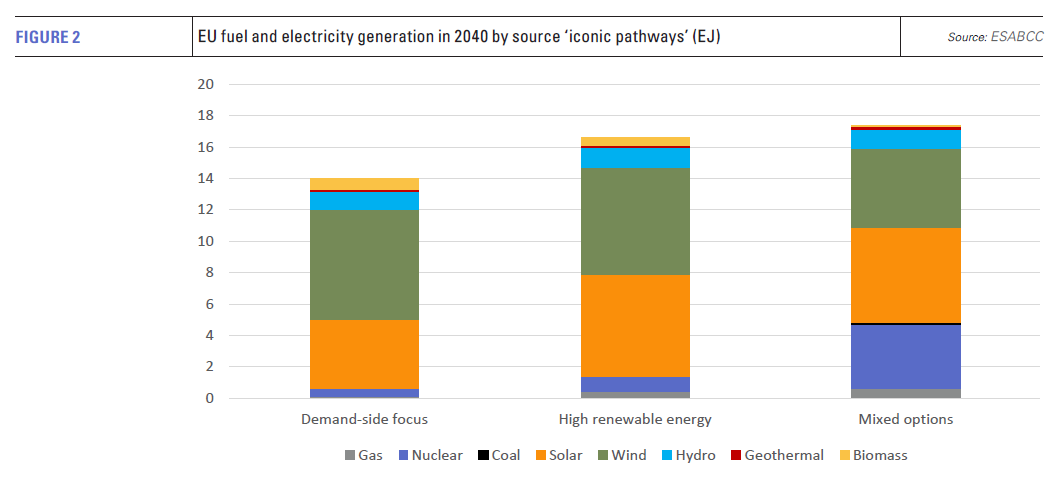

Different pathways all reduce gas use

There are, of course, different routes along the decarbonisation pathway. The report identifies three ‘iconic pathways,’ which represent the main groupings from 36 scenarios analysed (see figure 1). These are:.png)

- A demand-side focus pathway, which features the lowest level of final energy demand in 2040;

- A high-renewable energy pathway, which focuses on plausible emissions reductions in the short term and features the largest share of non-biomass renewable electricity generation in 2040; and

- A mixed options pathway, which provides the lowest net cumulative emissions in 2030-2050, the greatest deployment of carbon removals and the largest increase in nuclear generation.

However, common to all scenarios is that the power sector reaches near-to-zero emissions by 2040 and that it will be based predominantly on non-biomass renewables – wind, solar and hydro – the share of which ranges from 70-91% of electricity generation. In 30 out of the 36 scenarios, the share is higher than 85%. Power generation will be “almost completely free from unbated gas-fired generation by 2040, and from coal by 2030,” the report says.

All pathways also include large reductions in methane emissions from waste and from energy use, the latter’s reduction being in a range of 70-90%, owing to lower fossil fuel consumption.

Of the iconic pathways, the share of gas in fuel and electricity generation in 2040 is largest under the mixed options pathway, but still only amounts to about 0.5 exajoules (EJ), equivalent to about 16.7bn m3, a massive reduction from the 12.36 EJ (343.4bn m3) of gas consumed in the EU in 2022, itself down from 14.29 EJ in 2021.

Unsurprisingly, the scenarios with the highest use of gas are those with the largest amount of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), but even in the high CCS scenarios, natural gas use is residual in 2040. Over all of the 36 scenarios, the share of gas in electricity generation is 6% or less by 2040. In some, gas’ share of electricity generation falls to 1% or below by 2030.

Gas demand trajectories

The trajectories of gas demand vary considerably (see figure 2).

Under the demand-side focus pathway, gas-fired generation falls steadily until 2035 when it stabilises at 0.3 EJ, just over 2% of generation. On the high renewable energy pathway, gas-fired generation declines continuously after 2025 to 0.1% of generation by 2050. Under the mixed options pathway, gas-fired generation drops sharply by 2030, but then increases thereafter as a result of CCS.

Other sectors also see huge drops in gas demand. For example, across the scenarios, final energy demand in the residential and commercial sectors is supplied 53-71% by electricity, 7-19% by heat, 0-11% bioenergy and 0-27% by fossil fuels, most of which (5-20%) is natural gas. The remainder of fossil fuel use comes from oil with coal consumption ended.

The various scenarios envisage up to a 26% reduction in nitrogen fertiliser use between 2020 and 2030 and up to 34% by 2040. Similarly in industry and transport, decarbonisation options do not include significant gas use even if abated.

LNG import impact

The impact of such a radical decline in natural gas consumption would be huge in terms of imports. The report estimates that oil imports will fall by 50-100% compared with today, while gas imports drop by anywhere between 35-100%.

In most of the scenarios, the report says, imports of natural gas are largely eliminated by 2040. Given the sunk cost on the various international pipelines that supply Europe, residual gas imports are likely to by pipeline, suggesting LNG imports into Europe will fall dramatically in the 2030s, just after the market experiences a large uplift in supply from projects in Qatar and North America.

Recommendations are not law … yet

ESABCC’s recommendations are based on limiting the rise in global temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, an ambition which, from any perspective, is exceptionally challenging. Its recommendations are not law, but they will form the scientific backdrop to the recommendations for GHG emissions for 2040 which the European Commission will put before the European Parliament and member states at some point.

Setting the bar so high significantly limits the European Commission’s room for manoeuvre and the Commission is, in any case, committed to a science-based approach to climate change. The European Parliament will almost certainly adopt the ESABCC’s position and member states uncertain at the costs, both political and financial, will find it difficult to oppose.

Even if the target, or something close to it, is adopted, there is no guarantee it will be achieved. EU gas demand under the International Energy Agency’s STEPs scenario – which is based on prevailing policy settings – falls to 340bn m3 in 2030 and 235bn m3 in 2050.

Under its Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), which envisages an early peak in global natural gas demand, EU gas consumption falls to 242bn m3 in 2030 and to 45bn m3 in 2050, at which point domestic EU gas production is just 2bn m3.

Both are a far cry from the virtual elimination of EU gas imports by 2040. Even if the reduction of gas use by 2050 in the APS scenario is large, the timing is very different. And there are significant doubts about how fast new renewable energy capacity can be scaled up, particularly with regard to wind power and hydrogen production.

However, the EU will almost certainly adopt ambitious GHG targets for 2040. This will further dampen the confidence of gas buyers in the region, and reinforce LNG developers’ perception that the recent leap in European LNG demand is a time-limited bubble, albeit one with a very uncertain deflation path.