EastMed: the beginning of the end? [Gas in Transition]

The global shift to clean energy is creating uncertainties about the medium to long-term demand for oil and gas. This, in turn, is affecting investments in projects that need decades to return the required payback. This is particularly so for long-distance natural gas pipelines that now comprise the great majority of the longest pipelines at development stage worldwide – the estimate is 18 out of 20.

On top of these challenges, new long-distance gas pipelines face increasing competition from the growing LNG trade globally. The current energy crisis, especially in Europe, has strengthened the role of LNG in the global energy mix. Where price differentials are not significant, LNG offers higher flexibility.

EastMed gas pipeline

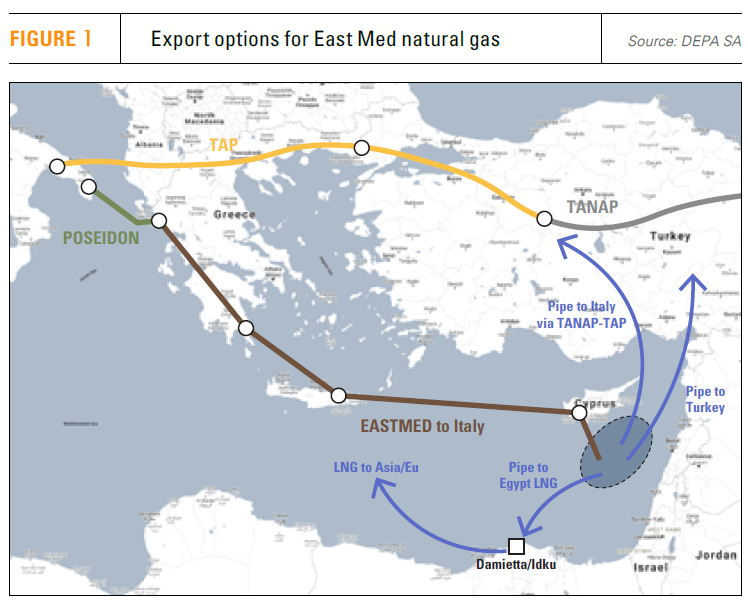

The immediate victim of these developments appears to be the much-talked about EastMed gas pipeline (Figure 1).

The US State Department issued a statement early January, in effect abandoning support for the EastMed gas pipeline. It pre-empts completion of the EU-funded feasibility study, which is expected by the end of the year. Following the reaction this caused, the US embassy in Athens clarified that “we remain committed to physically interconnecting East Med energy to Europe,” but “we are shifting our focus to electricity interconnectors that can support both gas and renewable energy sources.”

Amos Hochstein, state department senior advisor for energy security, said earlier that the project not only was not financially feasible, but it was also mostly “driven by politics,” while “multibillion-dollar deals should be driven by the commercial side.”

The US has taken this position in support of European green policy, but also because of president Joe Biden's shift to clean energy. It may also be the US desire to bring about a de-escalation in the region, at least for a project that is not going to be implemented. It simply recognises reality, which the three countries behind the EastMed, Israel, Cyprus and Greece, find politically difficult, except perhaps Cyprus’ new foreign minister, Ioannis Kasoulides. Soon after taking over his new post, he said construction of this pipeline was “up in the air from the start”, adding that all that remained was the confirmation that the project was unviable, which he had always known.

When the idea for EastMed first appeared in 2012 it had some basis. That is why it was included by the EU as a "project of common interest" (PCI) in 2015. At that time, the price of gas in Europe was around $10/mn Btu. From then until 2019 – pre-pandemic – the average fell to less than $6/mn Btu, a price at which EastMed is certainly not economically viable.

Now, due to the energy crisis, prices have risen to very high levels. But, at the beginning of 2022, they fell about 60% from the peak in October 2021 and are still in a downward – even if uncertain – trend. The expectation is that they will return closer to normal levels by 2023. With EastMed needing prices around $8/mn Btu for the next 20-25 years to be a profitable project, this makes it unsustainable.

In addition, since 2012 Europe has dramatically changed its energy strategy to focus on green energy, with the Green Deal and the Fit-for-55 package. These and the EU strategy to reduce use and dependence on gas, mean that Europe does not need new gas pipelines. It has made it clear that its goal is to reduce carbon emissions by 55% by 2030 and to eliminate them by 2050. These goals cannot be achieved through the continuous and undiminished use of unabated natural gas.

The EU is also introducing new gas legislation aimed at "leading Europe away from fossil fuels and natural gas to renewable energy sources (RES) and low-carbon gases, like hydrogen".

The inclusion of gas in the new EU Taxonomy is temporary and under strict conditions and for a limited time-period, that does not help a long-term project like EastMed. EU RES and gas policies have changed radically and no longer support new long-distance gas pipelines.

The EastMed is just a project that started with good intentions but lost its way. Since its inception, energy and gas markets have changed radically but the project has remained stagnant, stuck on justifications that have now been superseded.

Similar arguments apply to other options considered for exporting East Med gas to Europe. These include a route by-passing Cyprus, on-land from Israel to Egypt and then subsea to Greece, and the now resurrected from Israel to Turkey and from there to Europe (Figure 1). Turkish sources are touting the latter, taking advantage of the likely demise of the EastMed and the planned visit by the Israeli president, Isaac Herzog, to Turkey in March. Both options are subject to the same challenges as EastMed.

Only a dramatic and permanent rupture between Europe and Russia can, perhaps, change this. As a result of such concerns, there are even calls to reconsider the EastMed option in order to counter Russian gas – but these ignore Europe’s inexorable shift away from fossil fuels.

Regardless, there now seems to be a common will in the region to leave old thinking behind and move on to clean energy options.

The EastMed must now move forward with a new strategy based on renewable energy sources (RES), combined with energy storage, electricity interconnections and the use of natural gas regionally, in support of RES during the energy transition. In addition, the East Med Gas Forum (EMGF) should morph itself into an East Med Energy Forum and promote such strategies among its members

What about other long-distance gas pipelines?

For all intents and purposes the fate of the EastMed appears to be a harbinger for most long-distance gas pipelines – it is the beginning of the end. The exception is Russia’s plans for gas exports to China.

Russia to China

Not only Russia wants to diversify gas exports as the EU plans to reduce dependence on natural gas take effect, but also China’s demand for gas is growing in response to its drive to reduce dependence on coal in order to achieve net-zero by 2060. In fact, McKinsey estimates that gas demand in China will double by 2035.

More recently Russia’s gas pivot to China has been accelerated, perhaps as result of the evolving situation in Europe – giving Russia an alternative and longer-term market for its gas – but also as a result of shifting global geopolitics.

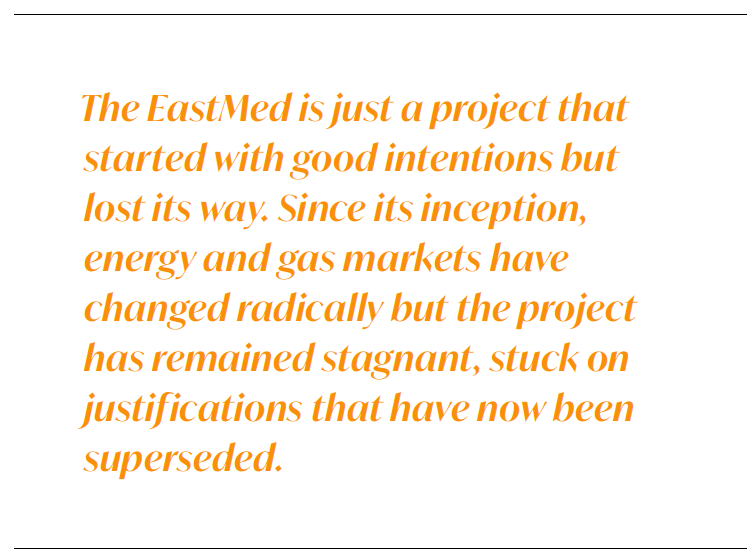

President Putin’s visit to Beijing on February 4 for the opening of the Winter Olympics and his meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping – the 38th between the two – not only cemented their cooperation, but it also produced an agreement to proceed with the construction of a new gas pipeline from Russia to China, following a Far Eastern route. It is a 30-year deal to supply 10bn m3/yr starting 2026, from Sakhalin to China’s Heilongjiang Province (Figure 2). Gazprom has confirmed that it signed a long-term sales and purchase agreement with China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) for gas to be supplied through this route.

Combined with the already operational Power of Siberia pipeline, it will increase deliveries of Russian gas to China to 48bn m3/yr. It is expected to become operational in two to three years and it is bound to impact China’s LNG import outlook.

There are also advanced plans to add a third gas pipeline, Power of Siberia 2, following a western route through Mongolia into western China, with a capacity to deliver 50bn m3/yr. With the pipeline having been given a go-ahead by president Putin in March 2021, and front-end engineering and design started by Gazprom at the same time, the two sides are expected to be in a position to sign an agreement later this year.

It will be owned jointly by Gazprom and CNPC and is expected to become operational in 2030, by which time China’s gas demand is likely to exceed Europe’s.

The challenge for Europe, though, is that this gas will be sourced from Yamal and East Siberia gas-fields. As a result, Europe may find itself competing with China for Russian gas. Given the challenges surrounding Russian das deliveries to Europe this winter, this may not be good news.

The question that arises is whether these projects signify a geopolitical shift, with China turning to more friendly countries to secure its future gas needs, at the expense of its growing dependence on LNG imports that may be vulnerable to geopolitical risk outside its control.

But with the cost of delivering Russian gas to China being quite competitive, it may threaten more expensive gas deliveries from central Asia, including Turkmenistan.

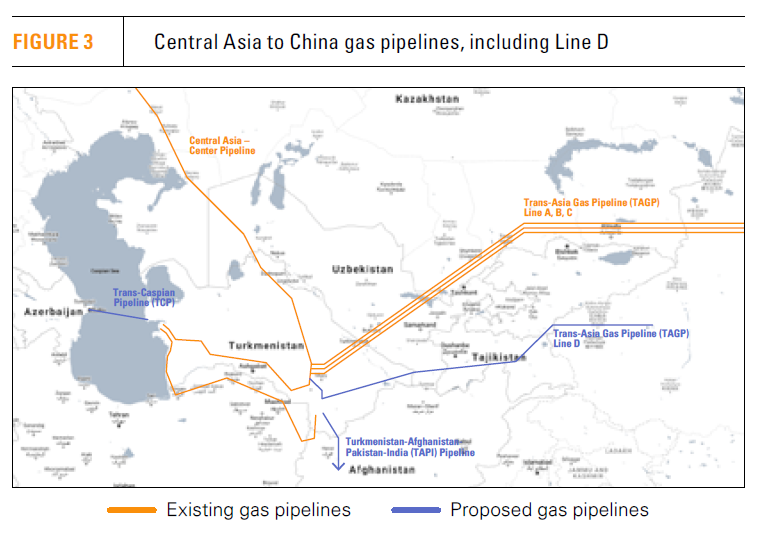

Central Asia to China Line D

China has been planning to increase gas deliveries from Turkmenistan by 30bn m3/yr through the 996-km Line D of the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan-China pipeline (Figure 3), owned by CNPC. But even though this is shorter than the existing lines, at an estimated $6.7bn cost it is still expected to be expensive and challenging. It may also be subject to risks from political tension that surfaces from time to time between the countries it will traverse.

This was originally scheduled to be launched by late 2016, but it has been delayed. Even though construction of the pipeline within Tajikistan restarted in 2020, it was soon suspended because of Covid-19 and it is yet to restart.

With Turkmenistan largely dependent on China for its gas exports, and transit countries Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan keen for transit revenues, China has full control of Line D and whether it goes ahead.

The risk, though, is that with Power of Siberia 2 now looking quite certain, Line D may no longer be needed by China.

TAPI

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline has been in planning since the 1990s, with an inter-governmental agreement signed in 2010. But it has not made any serious progress, other than construction of the pipeline in Turkmenistan that began in 2015 and was completed in 2019.

With an estimated cost likely to exceed $10bn and capacity of 33bn m3/yr, the 1,800-km pipeline will carry gas from Turkmenistan to Pakistan, and from there to India, passing though Afghanistan, but so far it has not attracted any major petroleum company participation. This is considered to be a major drawback in terms of attracting foreign investment, but also in terms of lack of technical expertise required to construct such a major pipeline.

Other risks are posed by the borders it will have to cross – often disputed and subject to cross-border attacks – and areas it will have to go through, especially in Afghanistan, where tribes have rights to lands. This will require cooperation with governments and militaries to resolve potential conflicts, increasing project risks.

Even though Afghanistan confirmed its commitment to the project at the end of January, the political instability and security concerns within the country pose major challenges, despite the potential benefits such a project can bring.

The importance of TAPI was discussed at a meeting in January between India and central-Asia heads-of-state, where it was agreed to resume talks on the project.

The energy ministers of Turkmenistan and Pakistan met in early February and agreed to set up technical working groups to develop a roadmap, including the gas price and the delivery point.

But with Pakistan already committed to LNG imports, TAPI gas will have to be significantly cheaper than LNG to attract serious interest. India is also giving priority to increasing indigenous gas production and to LNG imports.

With such security, funding and pricing challenges, the chances of this pipeline progressing further can only be considered to be low.

Iran to Pakistan and India

Iran and Pakistan agreed to start constructing a 22bn m3/year gas pipeline between the two countries in 2012, known as the Peace Pipeline, having started discussions in 1995. Iran has completed its section of the pipeline, but US sanctions have stopped any further progress. With Pakistan now committed to LNG imports, this project can now be considered to be dead.

In addition to this, Iran has been discussing the construction of a subsea gas pipeline to India since 2010, but without any signs of serious progress. India does not now appear to count on this, focusing on LNG imports.

Trans-Caspian gas pipeline

The Trans-Caspian pipeline, to transport gas from Turkmenistan to Europe, has been in discussion for over 20 years, but it continues to face serious challenges, with little prospects to progress.

This would involve the construction of a 300-km pipeline under the Caspian Sea to transport gas from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan, and from there to Europe through the Southern Gas Corridor. The EU has been very supportive of this project, seeing it as important to its gas supply diversification plans.

However, the geopolitics among the countries bordering the Caspian Sea and the disputed legal status of the Caspian are thwarting progress on this pipeline. It faces complex geopolitical and legal challenges that limit its chances of becoming reality. Climate change factors and Europe’s determination to shift away from natural gas in the longer-term make it even more difficult, despite short-term attractions.

North America

Long-distance oil and gas pipelines are experiencing growing resistance in North America from climate campaigners, who are mounting sophisticated legal challenges with increasing success. A good example is the demise of the Keystone XL oil pipeline, which was proposed to carry oil from Canada to Nebraska. This was eventually blocked by the US Supreme Court on environmental grounds. Subsequently, president Biden revoked a key cross-border presidential permit issued by president Trump, a decision that led to its abandonment in June 2021. This emboldened advocates for climate justice, redoubling their efforts in pursuit of their goals.

The strategies used to win the Keystone XL case are now being used by climate campaigners to stop other oil and gas pipeline projects in North America. In addition, with an increasing number of US banks pledging to fight climate change, pressure will only increase.

Even more importantly, judging from the increasing resistance long-distance oil and gas pipelines are experiencing in North America on climate change grounds, they are losing their social license, attracting more and more protests. It is becoming increasingly difficult for new pipeline proposals to progress.

Are we witnessing a geopolitical shift?

Are we witnessing a shift in global geopolitics that may start impacting global energy flows? Will the Russia-Ukraine conflict lead to realignment in Europe and hasten of the shift away from Russian gas or even speed up transition to renewables as the European Commission increasingly favours?

The Putin-Xi meeting statement astonishingly declared that “a trend has emerged towards redistribution of power in the world” towards China-Russia, and away from the US and the West, and that “the friendship between the two states has no limits.” Will this lead to a global realignment with fast shifting geopolitical interests also affecting global energy flows, both piped gas and LNG? Certainly, for their different reasons, Russia and China have strong political incentives to cooperate in the energy sector.

Increasing dependence of Russia on China for its gas exports, may subject it to longer-term risks, but closer geopolitical cooperation may outweigh that.

Only a few years ago China was showing limited enthusiasm for Russian gas. Now, in a short space of time, they are expediting two new pipelines that, with Power of Siberia, have a combined capacity close to 100bn m3/yr.

And it is not just pipelines, it is also LNG. China is a major investor in Novatek’s Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG-2 projects.

These are perhaps the reasons behind Gazprom’s hard stance refusing short-term or spot gas supplies to Europe, insisting on long-term contracts. Despite being accused by the International Energy Agency that it is not doing enough to boost gas supplies to Europe during this winter’s energy crisis, Gazprom insists that it has been meeting the volumes of gas it has committed-to in long-term contracts.

These developments must be of concern to Europe, given that it is not yet ready to shift away from natural gas in a significant way and given that it will find it difficult to replace all Russian gas. However, in the aftermath of Ukraine, even if the conflict does not escalate, it is possible that Europe will try to reduce future dependence on Russian gas.

But with the stand-off around Ukraine continuing, tension between Russia, the US and Europe growing, and the fate of Nord Stream 2 in the balance, and with Russia emboldened from its pivot to China, the future is uncertain.

And there could be more to come. With the two countries coming closer together and China’s energy demand growing, there could be even more projects exporting Russian gas to China in the future, eventually making up for reduced gas exports to Europe – as Europe shifts to renewables.

But in the short to medium term Europe will still need Russian gas and Russia will still depend on its gas exports to Europe. Once the Ukraine crisis is, hopefully, diffused, a new strategic balance will need to be reached.