Drilling Through the Spin - UK Shale Gas Exploration

Cuadrilla Resources, Britain’s first shale gas exploration license holder, claims a 500 square mile area around Blackpool, Preston and Southport contains enough methane to meet national gas demand for at least 50 years and create thousands of jobs. Proponents say Cuadrilla’s resource is revolutionary, opponents say shale gas is unnecessary. Who’s right? Tim Probert digs deep for the answer

Cuadrilla Resources, Britain’s first shale gas exploration license holder, claims a 500 square mile area around Blackpool, Preston and Southport contains enough methane to meet national gas demand for at least 50 years and create thousands of jobs. Proponents say Cuadrilla’s resource is revolutionary, opponents say shale gas is unnecessary. Who’s right? Tim Probert digs deep for the answer

2011 will go down in history as a year of revolution. Tunisia. Egypt. Libya. Blackpool… Blackpool? If Cuadrilla Resources is to be believed, this may not seem so brash.

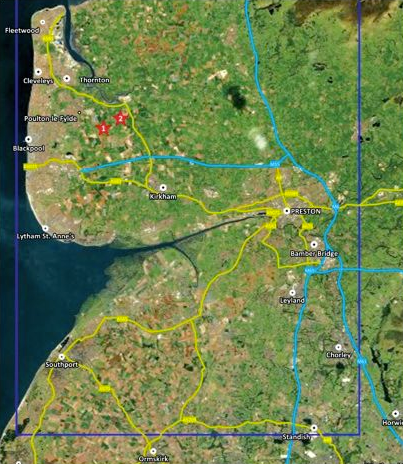

On 21 September, Lichfield-based Cuadrilla, a joint venture between Australian drilling firm AJ Lucas and American private equity firm Riverstone, announced a 500m2 area of the Bowland sedimentary rock basin in West Lancashire, for which it holds shale gas exploration licenses, holds a total potential resource of 5.66 trillion m3 of gas, or more than 10 times existing UK natural gas reserves.

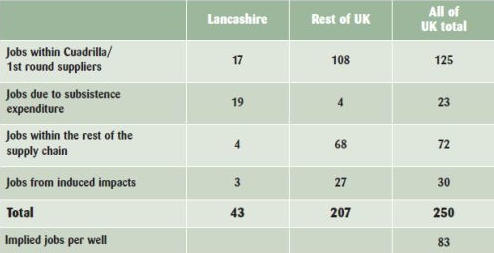

This figure came as a shock to the British Geological Survey (BGS), which officially estimates shale gas resources for the entire nation at 150 billion cubic metres. Cuadrilla said this volume of methane would meet UK natural gas demand for 56 years, lead to £120m in business rates being paid to local councils over 30 years, £5-6bln in tax revenues for the government, and up to 5,600 new jobs created with an average salary of £55,000.

This shale gas El Dorado is found predominantly to the west of the M6 motorway and includes the towns of Southport, Preston and Blackpool, some of the most economically deprived areas of the UK. Since Cuadrilla’s announcement, there has been a plethora of media reports focusing on how shale gas is a potential ‘game-changer’, a lifeline in hard economic times similar to North Sea oil in the 1970s and 1980s.

Much like nuclear power, the shale gas industry has more than its fair share of supporters and opponents. Prominent former Chancellor and energy minister, Nigel Lawson, calls shale gas ‘the most exciting technological development I can recall’. Others, particularly environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs), are less keen. Concerned about environment degradation and the impact on renewables investment, WWF has called for an outright ban.

The Bowland shale dates from the Carboniferous Period 363-290 million years ago. In contrast to conventional gas extracted from porous rock, shale is relatively impermeable, meaning gas cannot easily move through the shale the well is drilled in.

Getting down to it

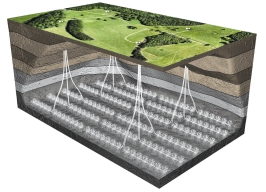

In order to release the methane, drillers use a method called hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, which essentially involves pumping a large amount of water, sand and chemicals at high pressure. Cuadrilla intends to use a technique called pad drilling, with up to 10 drill wells radiating horizontally for distances of up to six miles from a single site, or pad. This technique has been used for decades, but the improved ability to steer drillbits using off-the-shelf technology has made horizontal fracking cost-effective. The facility to perform surface data acquisition to locate gas in the rock, rather than drill right through the shale as previously, has also brought down costs.

It must be stressed that Cuadrilla’s figure of 5.66 trillion cubic metres is for ‘gas in place’ in the Bowland basin and not proven reserves. It is very much an estimate, calculated by multiplying the area of shale rock by an average figure of how much gas may be extractable from this particular type of shale.

James Elston, CEO of London-based shale gas consultancy Palladian Energy, says the most that could be realistically extracted is 20%. That would be roughly equivalent to the Troll gas field in the North Sea, which holds 60% of Norway’s gas reserves. ‘But they’ve only drilled two wells,’ notes Elston. ‘Only when they’ve done seven or eight fracks over a wider area will we get a true idea of how much shale gas is down there and how much can be got out.’

Standing in the way of development

Despite the huge potential reserves of shale gas in the Bowland basin and elsewhere in the UK, there are many factors that may hamper development – firstly, the huge controversy over fracking.

Cuadrilla was forced to halt drilling in May when the BGS suggested fracks at depths of 2.0 and 2.7 kilometres caused two small earth tremors with magnitudes of 2.3 and 1.5 on 1 April and 27 May respectively. Cuadrilla met with the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) on 13 October to discuss how the developer intends to mitigate the risk of earthquakes. DECC is currently evaluating the report in tandem with the BGS before it will allow exploratory drilling to resume.

There is also considerable concern over the impact on water supplies. Cuadrilla expects to use 13,000m3 (1,000 for the drilling process, 12,000 for fracturing) per well in a six-well pad. Of this volume, equivalent to five Olympic swimming pools, approximately one-third returns to the surface.

Cuadrilla’s fracking fluid consists of 99.75% water and sand, with the remaining 0.25% comprised of three additional ingredients: a friction reducer called polyacrylamide, a biocide to purify water and a weak hydrochloric acid to help open the perforations to initiate frack fluid injection.

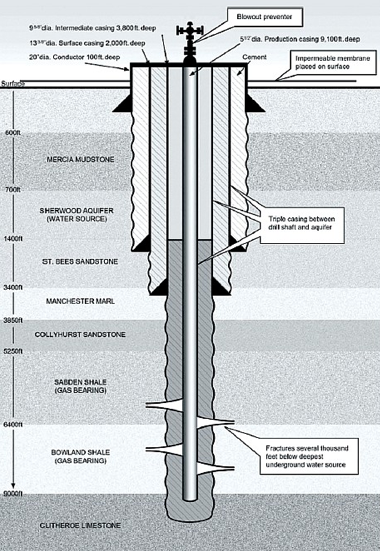

As the fracking process takes place several thousand feet below the layers of aquifers, DECC believes it is highly unlikely they will be polluted. However, the USA’s Environment Protection Agency has found there is a serious risk of groundwater pollution from improperly constructed wells, for example where boreholes have not been cased with a steel pipe cemented in place. Cuadrilla says its boreholes will be triple-cased between the drill shaft and the aquifer, while the site will be protected by an impermeable membrane to guard against surface spills - see diagram:

Due to UK ownership rights, where mineral rights belong to the Crown Estate and not the landowner, DECC expects shale gas development to be relatively limited. Shale gas drillers have to obtain an exploration license from DECC, but it is up to local councils to allow developers to exploit the shale. This may limit shale gas development in less economically deprived areas such as the Weald Basin, which covers Kent, Sussex and Surrey.

Energy minister Charles Hendry MP says, ‘Getting permission from property owners and landowners will be challenging. Visually, however, these are not intrusive facilities and are of a short-term nature. I think people can be persuaded about shale gas for the wider national good and local benefits in terms of job and wealth creation.’

Spot the difference

The Bowland basin is often compared to the vast Barnett shale in the USA, which provides five per cent of US gas supply, as they are both Carboniferous rock. As Abhen Panther, Senior Geologist with Henley-on-Thames’ RGS Energy, explains, there are some very important differences.

‘The Barnett shale has flat, plane-like deposits. The drilling can go on for miles, flat, in one direction with a good chance of intersecting the shale gas. The Bowland shale is a narrow shoestring rift basin characterised by typical rift scale tectonics. This geology needs complex multi-lateral wells with fancy footwork in order to hit the target.

‘Bowland shale is thicker than anything in the US, where gas reservoirs are typically 100 metres thick. Rift basins are very thick, with gas reservoirs up to around 1,000 metres. That’s why Cuadrilla is quoting 200 trillion cubic feet, but whether they can get it out is a challenge.’

Shale gas wells decline rapidly – Cuadrilla says the typical decline rate is 40% within two years. To exploit the Bowland basin successfully, Cuadrilla may need to drill six to eight boreholes per square mile and up to 50 wells a year, at a cost of £10.5m each.

The lack of suitable drilling rigs, however, is the most important issue impairing shale gas production, according to Joseph Dutton, Unconventional Gas Analyst at Canterbury-based energy researchers Douglas-Westwood. Deep, multiple-stage fracking ideally requires a drilling rig with at least 2,000 brake horsepower (BHP), says Dutton.

‘We’ve identified only 78 rigs in western Europe, 49 of those have a rated torque of less than 1,500 BHP, 17 have 1,500-2,000 BHP and only 12 with greater than 2,000 BHP. There are big bucks to be made from companies able to step in and address drilling rig issues.’

Those who assume shale gas production will suddenly explode, as in the USA where it accounts for around a quarter of natural gas supply, may be disappointed. The UK may not become a significant producer of shale gas until 2020, says Dutton, as costs of production are around four times more than pipeline natural gas and twice that of imported LNG.

Elston says, ‘Rabid proponents who say shale gas will lead to lower natural gas prices are being disingenuous. What it does is offer a subsidyfree energy source with security of supply, jobs in depressed areas and government revenue, but it won’t change the need for zero-carbon sources of energy.’

Shale gas is not the environmental catastrophe some NGOs would like us to believe. Equally, it is not quite the cheap and abundant source some proponents say. The shale gas ‘revolution’ appears not to be quite so revolutionary. At least, not yet.

All images courtesy of Cuadrilla Resources

Re-published with the consent of Material World, the member magazine of the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining