Don’t Expect Shell to Transform Energy! [Gas Transitions]

When it comes to how incumbent oil and gas companies like Shell will be coping with “the energy transition” and “decarbonisation”, maybe you have, like me, two voices in your head. A hopeful one and a sceptical one.

I was attending a presentation the other day by Ed Daniels, executive vice-president Strategy & Portfolio of Shell, at a Deloitte Oil & Gas conference in Rotterdam, and as usual when I listen to Shell presentations, my two voices started discussing with each other about what to think of what I heard.

In his presentation, Daniels explained how Shell was “setting the course to become a future-proof energy company.” Although I am sure he was sincere and had some good arguments, he didn’t quite convince me. So I decided to take another deep dive – I have been following Shell for some 18 years now – into the company’s energy transition strategy as expressed in its latest investor presentations, executive speeches and other documents. That didn’t stop the discussion in my head – in fact, it became only more intense. It went something like this:

Sceptical voice (SV): Having read Shell’s latest investor presentation, given June 4-5 (you can find a complete transcript on the company website), and the latest speeches from their executives, I can only conclude that it’s useless to expect Shell to transform the energy system. They are followers at best, but they will never be leaders, whatever they say.

Hopeful voice (HV): What makes you say that? I find their actions quite impressive. They have a unique Net Carbon Footprint (NCF) ambition, which they announced in November 2017, promising 20% emission reductions by 2030 and 50% by 2050. And mind you, that reduction does not just apply to their own activities, but also to the use of their energy products by their customers! What are technically called scope 3 emissions. No other oil company has gone that far. Last year they also came out with their Sky scenario, which they say is “a technologically, industrially, and economically possible route forward consistent with limiting the global average temperature rise to well below 2°C from pre-industrial levels.” Last but not least, it is putting its money where its mouth is. As Maarten Wetselaar, director of Integrated Gas and New Energies, tells us in the investor briefing, it has set up a New Energies division, which has invested in biofuels, electricity retailers, a battery storage company (Sonnen), an EV charging company (NewMotion), offshore wind projects and solar companies. It looks to me like it has some idea of where it’s going.

SV: Really? I am not so sure. I don’t think the New Energies division represents a strategy. At least not yet. It’s mostly a bunch of start-up companies it has scooped up. But it has no idea yet where this will be going. Will it become a major solar and wind energy player? Does it believe in a hydrogen economy? A bio-based economy? When he talks about ‘new fuels’, Wetselaar says: “We are positioning to scale up when the time is right.” And Van Beurden says: “We must absolutely ensure we get our approach right for this theme [i.e. emerging opportunities in the power sector] and we will not get ahead of ourselves.” That sounds to me like wait-and-see.

Actually, when you read what Wetselaar says about how Shell sees itself operating in the future energy market, it’s quite interesting. He says that: “Customers of the future will have more choice driven by technology and we can expect to see increasing intermittent demand from charging and heating and cooling. And of course, there will be intermittent supply such as from solar and wind power, and the rise of distributed energy resources and storage solutions and more. This transformation is disrupting incumbents and challenging their business models, creating opportunity for new entrants. And with this, we see new value pools being created in this integrated system.” In other words, he sees Shell as a “new entrant” disrupting incumbent businesses! How ironic. I can’t really see Shell in that role.

But OK, let’s suppose, for the sake of argument, that it does succeed with New Energies. Then what? I will tell you: then it won’t be Shell any more. By transforming itself, it will creatively destroy itself.

HV: You’d better explain yourself.

SV: Well, what is Shell? An oil and gas company, yes. And at the same time: a cash generating machine. A dividend machine. Daniels made the point in Rotterdam that Shell is the largest dividend payer in the world. And Van Beurden and his colleagues make it quite clear in their investor presentation that they have no intention of changing the nature of the beast. Van Beurden says: “We will continue our focus on fully sustaining our Upstream business well into the coming decades. For as long as there is sustained demand for oil and gas, there will be sustained commitment from Shell, and that means sustained investment.”

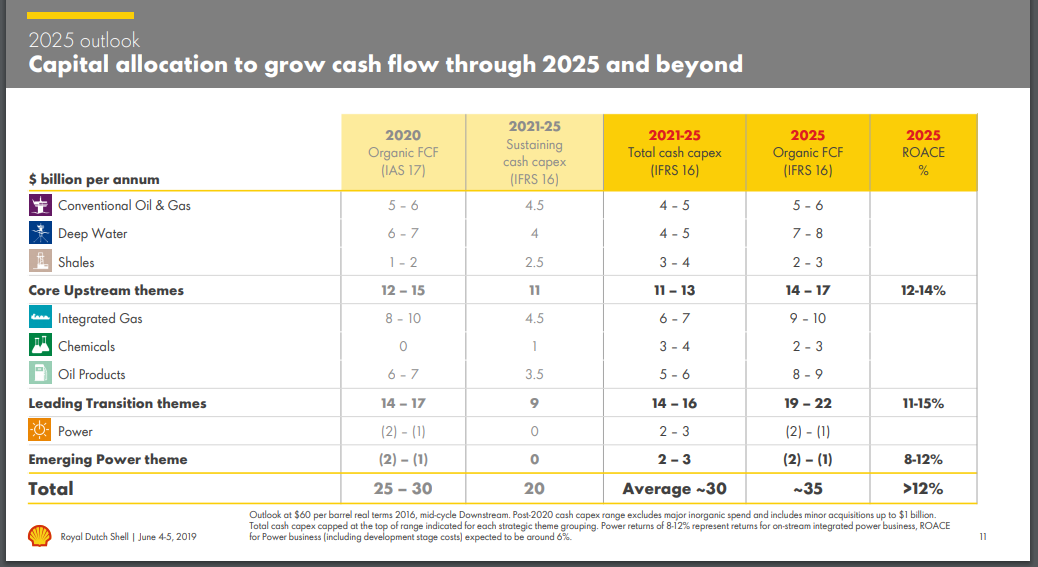

Shell’s main priority, he adds, is “being a world-class investment case. We plan to be generating some $35bn of organic free cash flow by 2025. This strong cash outlook will create the potential to distribute to our shareholders a cumulative cash amount of $125bn or more over the five-year period from 2021 to 2025. ... We expect a return on average capital employed of more than 12% by the end of 2025. … We expect cash capex to average around $30bn/yr in 2021 to 2025…. Of the $30bn average, some $20bn/yr would be required to sustain our portfolio and deliver cash flow from operations at 2020 levels.”

He showed this chart to illustrate how they will be spending their money:

Source: Shell’s Management Day, Delivering a World-Class Investment Case, June 4-5, 2019

Source: Shell’s Management Day, Delivering a World-Class Investment Case, June 4-5, 2019

You can see that the overwhelming majority goes to oil and gas, not to any “New Energies.” And the gas sector can rest assured: the Shell executives go out of their way to stress the immense importance gas has for Shell and will continue to have. As Wetselaar puts it: “For Shell, gas is a fuel for today and a fuel for the future.” So it’s really business as usual for Shell.

HV: Come on, be reasonable, you can’t expect them to turn around in a few years. Everyone knows the energy transition will take many decades. The point is that Shell’s Net Carbon Footprint ambition is compatible with the Paris Agreement. Van Beurden said so at Shell’s Annual Shareholders’ Meeting in May 2018, as you can see on this video here, published by Follow This, a group of activist shareholders who are trying to get oil companies to commit to the Paris Agreement. Our Net Carbon Footprint ambition is “completely consistent and compatible” with the Paris Agreement, says Van Beurden. When he is challenged by Mark van Baal, the founder of Follow This, he notes that Shell’s Sky scenario, which projects net zero emissions by 2070, leads to 1.75 °C warming, well within the 2 °C limit. And the Sky scenario has been checked and approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

So Shell’s plan is to transform itself over the next few decades to adapt to the Sky scenario. The Net Carbon Footprint ambition is part of that transformation. Van Beurden called it a “mid-point”. How will Shell do this? This slide from the investor presentation is really key to Shell’s strategy:

Source: Shell’s Management Day, Delivering a World-Class Investment Case, June 4-5, 2019

Source: Shell’s Management Day, Delivering a World-Class Investment Case, June 4-5, 2019

So you see, they do have a plan, but it will take time.

SV: I agree that this is a key slide! Absolutely. Isn’t there something that strikes you as odd about it?

HV: Well, what?

SV: It doesn’t show any figures! How unlike Shell. And how different from when it is talking about cash flow or oil and gas production. What are we supposed to think about these coloured bars? Will natural sinks be the main instrument for Shell to reduce emissions, since this is the largest bar?

But never mind. Let’s suppose it does move in the direction this slide indicates. How is it then going to keep up being “a world-class investment case”? With renewable power, electric mobility, CCS? You see, that’s my point. Shell won’t be Shell any more.

HV: What makes you so sure of that? Van Beurden stresses that “we must deliver returns in the 8-12% range for our onstream integrated power business.” And Wetselaar says: “We are not interested in this business because of the returns that the utility industry traditionally delivers. Instead, we believe we can build a modern integrated power business that delivers returns of 8-12% when on stream.”

SV: An 8-12% return on natural sinks? On CCS? How are these ever going to be cash cows? How are solar and wind going to become cash cows? Everybody can make solar panels. Everybody is already making them. Does anyone really believe that making use of “new value pools” is going to yield the same dividends as producing oil and gas? I think Shell is up against a huge credibility gap here. They promise continued high investments in oil and gas and continued high dividends, yet they also promise to transform themselves into a “New Energies” company that will kiss oil and gas goodbye. And then they will make the same returns? Look at their Sky scenario and see what little role there will be left for oil and gas. You will be shocked. I don’t see how they can make that transformation and still keep on being a dividend machine.

By the way, I doubt very much that Shell’s Net Carbon Footprint ambition is aligned with the Paris Agreement. Mark van Baal challenged Van Beurden on this point and I must say I tend to agree with Van Baal. What you have to understand about the Net Carbon Footprint idea is that it is a carbon intensity target. In other words, it’s a relative target, not an absolute one. Shell promises to reduce the carbon intensity of their products, including the products used by their customers, from “79gCO2e/MJ to 40gCO2e/MJ”. But that means if energy demand goes up, as it likely will, carbon emissions will still rise. If you assume, as Shell does, that energy demand will grow 40% to 2050, then the Net Carbon Footprint reduction is only 30% in absolute terms. As Mark van Baal pointed out to me, to be in line with Paris requires a 70% reduction, that’s the average of all scenarios accepted by the IPCC.

HV: I agree that none of this will be easy. Shell doesn’t claim it’s going to be easy. It repeatedly says it’s a huge challenge. And of course the company will not be the same in 2050 as it is today. But I don’t see any reason why it couldn’t still be thriving and profitable by that time. If not, what would that imply for our economic future? If they can’t do it, who can?

SV: That’s a very good point. Maybe no one can. You know, I think the problem with how Shell is presenting this transformation is that it likes to convey to their shareholders that it can make the same kind of money on “new energies” as it does on oil and gas. “Shell can thrive through the transition of the global energy system,” says Van Beurden. He actually says that four times in his presentation! I am sure Van Beurden is an honourable man, but I feel he is giving his company a bit too much praise. Wetselaar, in a speech he gave in Houston recently, compares today’s transition to the switch from horses to oil in the early 20th century. But oil of course was a clear improvement over horses in the value it delivered. Today’s transition to renewables is not an improvement! That’s the gist of the whole matter. We are not doing this because we have found something superior to oil and gas. We are doing it because it’s necessary. And I am not even talking about something like CCS, which is only a cost, not a value at all. So it’s an error to think that we won’t be worse off economically if we switch away from oil and gas; and that Shell will remain the cash generating machine it is now.

HV: I see your point. Unless perhaps we can create an entirely new society where value is derived in totally different ways. Fossil fuels do have disadvantages after all, like air pollution and import dependency. We may be able to create an economy where something like solar power may actually work better than fossil fuels, if you see what I mean. I am not sure if I am explaining myself very well.

SV: I think I understand what you are getting at. Although it sounds more like a hope than a real plan. Actually, I think this is what Shell executives are also increasingly hinting at. I was surprised to hear Daniels say in Rotterdam that “we need to start having difficult conversations about our consumption patterns.” He suggested we should stop eating strawberries in December. Van Beurden made the exact same point about consumption patterns and strawberries in speeches he gave in June at The Times CEO summit and on July 3 at the Shell Energy summit. He also said: “Some of my children are passionate about both climate change and clothes. I like to point out to them, having something new for every season four times a year is creating quite a significant ecological footprint.”

The Shell executives also keep harping on the importance of collaboration in all their speeches. They can’t do it alone, they keep saying. They need society to help them. They are even sounding a little desperate. Van Beurden said at The Times CEO Summit: “I am here to ask for your help.” An energy company, he said, “cannot set consumption patterns on a national or global scale – it simply cannot.” So Shell is aware that if we really want to go to net zero, we will be in a different world altogether.

HV: So isn’t it unfair then to keep demanding that Shell is responsible for climate change and that it has to transform the energy system? Can you expect it to do that?

SV: You said it. You can’t. Exactly my point.

A note to my readers

I will be on holiday for the next three weeks. Thanks to all of you who have been following this space. I hope to be back again on 6 August. Don’t hesitate to send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com