Demand rush will push back LNG market rebalancing [Gas in Transition]

In a world of high LNG prices, investment in new regasification capacity might be expected to wither, but that seems to be far from the case, owing to the vital role LNG is playing in meeting both environmental and security goals.

In terms of LNG demand, Europe’s response to the loss of Russian gas imports has been rapid. Any under-used capacity that can be used has been.

Moreover, the deployment of two floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) in early September at the Netherlands Eemshaven Energy Hub has been extraordinarily quick by any standards. The Netherlands has managed to add 8bn m3 of LNG import capacity in less than a year. This will be complemented by the expansion of the country’s Gate LNG terminal, doubling capacity from 12bn m3 prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to 24bn m3.

Germany is not far behind. A memorandum of understanding struck between German utility RWE and ADNOC, the UAE’s state-owned oil and gas company, implies that the first LNG cargo to be imported into Germany could arrive by the end of this year. The cargo will unload at the Elbehafen LNG facility, which is still under construction at the port town of Brunsbüttel near Hamburg. Uniper’s FSRU project at Wilhelmshaven is also targeting its first delivery for the end of the year or early 2023.

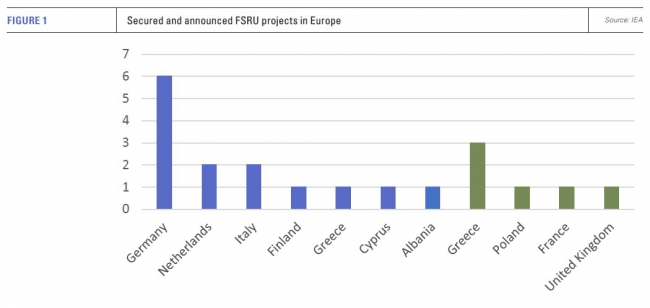

Germany in total has contracted five FSRUs and has plans for a sixth (see figure 1). FSRUs at Stade, where construction has also started on an onshore LNG regasification terminal, Lubmin and a second vessel at Wilhelmshaven are expected to be operational from the end of 2023.

Under ‘normal’ conditions, and depending on the site, FSRU installation usually takes at least one to two years.

FSRU supply

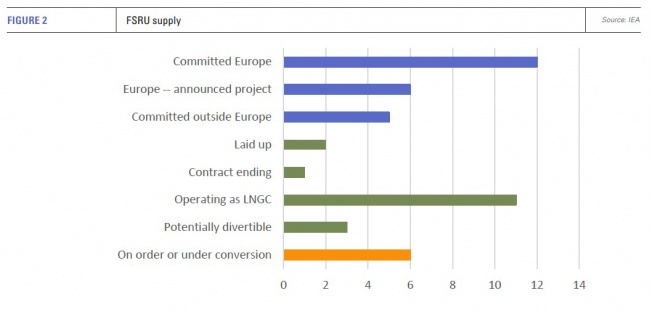

The ability to supply so many FSRUs in short order is, in part, a matter of luck (see figure 2). The market for FSRUs expanded quickly in 2014-15 leading many fleet owners to invest in new capacity on a speculative basis, but the expected demand did not materialise. By 2019, a rapidly expanding fleet of FSRUs saw almost a third of its capacity operating as LNG Carriers (LNGCs).

This surplus is now rapidly diminishing. In addition, another consequence of the period of oversupply was that new orders declined. Fleet developers are once again turning to new construction, but lead times for new vessels are long, owing to a similar rush in orders for LNGCs and container ships from the limited number of shipyards that have the capability to build FSRUs.

Excelerate Energy, for example, in early October reached an agreement with South Korea’s Hyundai Heavy Industries for a new FSRU with storage capacity of 170,000 m3. The vessel’s expected delivery date is not until June 2026.

In its latest Gas Market Report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) warns of fleet capacity constraints stemming from the surge in European demand for FSRUs. The IEA says that as of mid-2022, European importers had secured 12 FSRUs and that at least six additional projects had been announced. Five FSRUs were also booked for operations outside of Europe. Set against new demand for 23 vessels, available capacity only amounts to 14 FSRUs, not all of which are ready for operation, and six under construction or in the process of conversion. This suggests that to meet European demand, FSRUs may have to be redeployed from other parts of the world.

European demand may prove even higher. Ireland, for example, appears to be re-examining its formerly anti-LNG stance. The government in September suggested an FSRU and gas storage capacity could be employed to address potential disruption to gas supplies, which are currently sourced primarily from the UK amid declining domestic Irish output.

European demand may prove even higher. Ireland, for example, appears to be re-examining its formerly anti-LNG stance. The government in September suggested an FSRU and gas storage capacity could be employed to address potential disruption to gas supplies, which are currently sourced primarily from the UK amid declining domestic Irish output.

More broadly, across Europe, the new FSRU capacity falls short of matching former levels of gas imports to Europe from Russia, even when higher utilisation rates for existing regasification capacity are taken into account. The IEA estimates that European charters of FSRUs could add over 60bn m3 of new LNG import capacity by 2025, much of which will be ‘must-run’ capacity in the current energy insecure environment.

Outside the European gas bubble

Demand for LNG outside of Europe has certainly been crimped by high prices and scarcity of supply, but the investment cycle for LNG is much longer, so far at least, than the European gas crisis.

The Philippines is expected to enter the LNG market for the first time early next year, with the launch of three LNG import terminals. The government has sanctioned a total of six LNG import projects over the next three years.

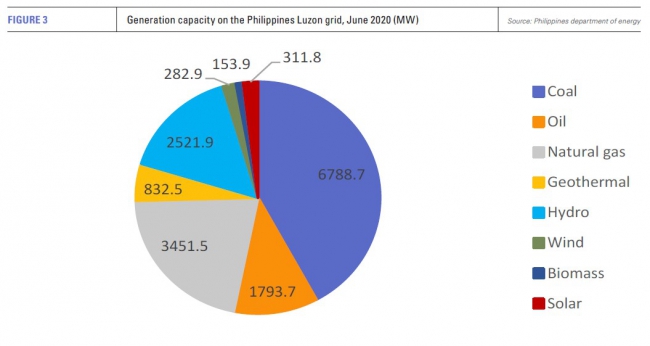

The Philippines new president, Ferdinand Marcos, has said he will maintain a moratorium on new coal plants, which was introduced by the former administration in 2020. Coal-fired generation is expected to be maintained for some time, but the prospect had been for a mix of renewables and an expanding role for gas to gradually allow a reduction in coal use.

Gas is critical for power generation on the Philippines’ Luzon grid (see figure 3) and LNG is needed to replace declining gas output from the major Malampaya field. Power generation accounts for almost all of the country’s gas output, with industry accounting for the remainder. The Philippines’ need for LNG will add to demand in a supply constrained market, and, if prices remain high, an expanded role for gas in the country’s economy now looks less certain.

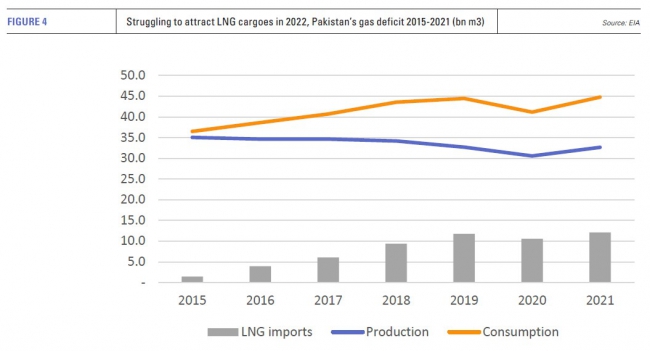

Pakistan also faces constraints (see figure 4). State-owned Pakistan LNG issued a tender for a total of 72 shipments in August in two parts, with delivery periods later changed to receive 24 cargoes from January 2023 to December 2024 and then 48 cargoes from January 2025 to December 2028. According to the company, it received no bids for either delivery period.

Earlier tenders for LNG also failed to attract interest. The country has suffered severe floods this summer that have badly affected power distribution infrastructure and damaged gas pipelines. The lack of imports leaves the country facing a substantial gas deficit, power shortages and increased fuel oil imports for power generation.

Yet amid the crisis, state-owned company Pakistan State Oil has announced plans to build a new LNG import terminal near the capital Karachi, including what would be the country’s first LNG storage facility. The country’s two existing terminals are further east at Port Qasim. Few details about the project were released, but PSO CEO Syed Muhammad Taha said the terminal would take about four years to complete.

The announcement suggests that LNG is not falling out of favour as a medium-term means of addressing climate goals and energy security for a country which already faces a gas deficit and which, like the Philippines, is very dependent on higher carbon fuel sources for power generation, in this case fuel oil and coal.

The new import terminal could come on-stream at the same time that LNG supply is expected to see a large jump with the completion of Qatar’s major North Field expansion and new export capacity in the US and possibly also Mexico.

Brazil last year also proved a major market for LNG, prompted by severe drought which limited power generation from hydropower. LNG imports into the country reached a record 10.1 bn m3. Although imports are expected to be lower this year, market opening and an expected rise in regasification facilities from five to eight in the next few years will at least create the capacity to import more LNG, even if domestic and regional gas sources will be preferred.

Short or long-term crisis?

Europe’s gas crisis has not yet been sufficiently extended to throw long-term plans off course. In addition, some plans, and the problems they seek to address, are simply too near term to find other solutions. As a result, regasification capacity looks set to significantly outstrip new LNG supply coming to the market at least until 2026/27, implying some of the new capacity will experience very low utilisation rates at least in their early years.

A report by GlobalData published in June suggests that China will continue to lead in terms of regasification capacity additions. Overall, it says global regas capacity will rise 48% from 2022-2026, with Asia accounting for 75% of the new capacity.

This implies that the global LNG market will take some time to rebalance. In the short term, Europe looks like it will get through this winter, but only with some concerted conservation efforts. Gas rationing for industry, if the winter proves cold, looks highly likely.

Even then, it will do so only at the cost of severely depleted levels of gas in storage. It will have to rebuild these over the summer of 2023, potentially with no Russian gas imports whatsoever – a much tougher call than this year. Demand for LNG should therefore remain very strong and, despite additions to import capacity, Europe could enter winter 2023/24 in a worse position than it is now.

Building resilience over the next five years is very dependent on increased LNG imports because renewables and storage need time to reach higher levels of deployment, particularly offshore wind, while switching away from gas in industry and heating is also challenging. If the increase in demand for LNG for Asia is also factored into the equation, then LNG prices look certain to remain strong at least until 2026/27.

It is possible that even the expansion of Qatari and US LNG could be mopped up, given the weight of coal-to-gas switching implied in Asia by its current regasification plans. These are and will remain price sensitive, but climate change targets will not disappear as a result of a renewed focus on energy security. Asian coal-to-gas switching is an exceptionally deep fall-back for the LNG market, one which is still in an expansionary phase and which will only gradually be challenged by faster renewable energy deployment.