Credit risk for growth [NGW Magazine]

India and Pakistan represent vast and exciting new markets for LNG exporters, but the energy sectors of both have endemic debt problems, which will hamper the growth of their respective gas markets and thus the timing of increased LNG imports.

India and Pakistan represent vast and exciting new markets for LNG exporters, but the energy sectors of both have endemic debt problems, which will hamper the growth of their respective gas markets and thus the timing of increased LNG imports.

On paper, the prospects look almost surreal. India is soon to overtake China as the most populous nation on earth. Pakistan, already a heavy gas user in relative terms, with over 200mn people, ranks sixth. While project implementation is slow, both countries are undertaking major extensions to their existing gas grids, based around new LNG terminals as the supply source.

India’s Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board sees gas’ share of the energy mix rising to 20% by 2025 from just 6.7% of primary energy in 2017. Pakistan, meanwhile, is using LNG to meet a long-standing gas deficit, as well as substituting high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) for gas in power generation.

Both have broad demand bases, ranging from fertiliser production, through power generation and city gas to transport, with huge capacity for growth. Both have natural gas vehicle fleets of just over 3mn, which in Pakistan represents almost 14% of the total, according to NGV Global. India is switching to compressed natural gas from diesel in its urban bus fleet to improve air quality.

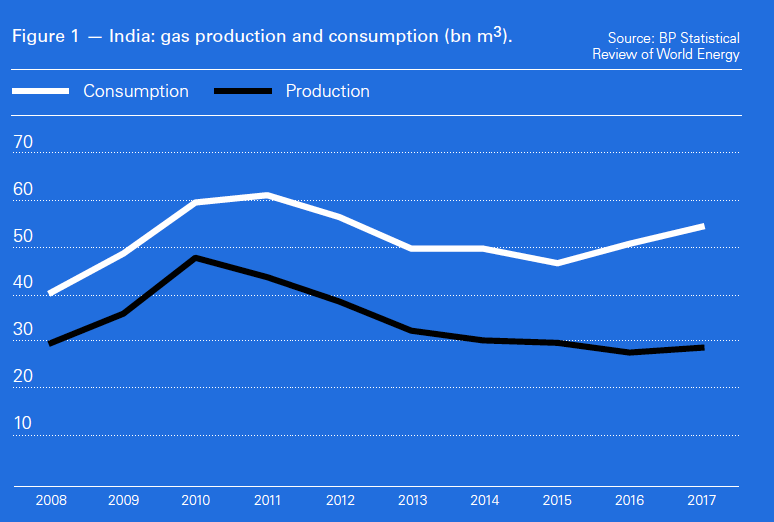

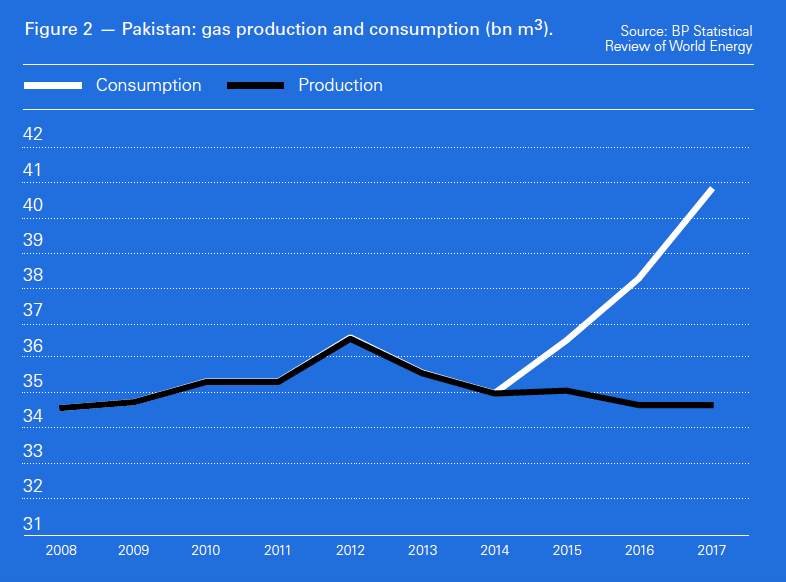

Indian gas production rose in 2017, but this followed a period of decline from 2010 to 2016, and demand growth is still outstripping forecast rises in supply. Pakistan’s domestic gas supply has stagnated at just under 35bn m³/yr for the last decade and the government forecasts a decline of about 5%/yr until the end of 2022.

It all boils down to two huge markets, familiar with gas technologies, in deficit, with fast growing demand for gas, which, it would appear, can only be met by LNG, various major pipeline proposals notwithstanding.

The devil, however, is in the detail.

Credit issues

Take a look at the countries’ sovereign debt ratings in relation to the world’s largest LNG importers and consider how deeply embedded in energy supply and distribution state-owned companies are in both countries. India comes in at Baa2 and Pakistan at B3, compared with Japan at A1, South Korea A2, and the relatively new kid on the block China, again A1, according to ratings agency Fitch.

Although both have private and foreign operators, it’s clear that in the search for new markets, LNG producers are taking a big step downwards in terms of counter-party credit worthiness.

The problems run far downstream. Urea production consumes the largest share of gas supply in India. Gas demand in this sector has risen strongly since the government created a price pooling system, which serves to average out LNG costs with cheaper-priced domestic gas supplies. The government is pursuing self sufficiency in fertiliser production, making the sector a long-term growth centre for gas demand.

.png)

Rising demand is of course welcome, but price pooling demonstrates the sensitivity of urea production to price. Moreover, the market price of fertiliser is subsidised by the government, which makes the sector’s gas demand dependent on a policy which creates government debt.

Look also at electricity, which is distributed by companies owned by state governments. These companies exist in a state of near perpetual bankruptcy, which has culminated in periodic financial bailouts over the last 20 years.

The problem is not difficult to grasp. Regulated electricity prices are set below the level of cost recovery. This is a problem for all generators, but especially so for LNG as LNG-to-power is at the high end of the spectrum in terms of generating costs.

Indian governments depend critically on the political support of the country’s huge rural population and while measures have been taken to reform electricity prices, they have not been implemented, often owing to state and local-level resistance. Electricity prices are kept below cost recovery to gain political favour.

As a result, the state distribution companies build up debts which should be paid by the state governments, but these too are cash-strapped.

The lack of funds stymies investment. It makes the state distributors unreliable customers for gas and/or for electricity generated from gas, which is more expensive than coal-fired generation, onshore wind or solar. The upshot is that the distribution companies often choose power cuts over buying gas-fuelled electricity to avoid a further build-up of debt.

The credit problems go deeper still, however, as the government has used state-owned banks to provide debt to the teetering distributors. In the absence of pricing reform, this will remain bad debts at the heart of the Indian banking system. This interconnectivity suggests potential for systemic credit problems.

The power minister of the day Piyush Goyal reported to parliament in July last year that about 57% of India’s 25 GW of gas-fired generating capacity was stranded for lack of gas, while the remaining 11 GW was operating well below capacity. Gas consumption rose by about 7% in both calendar 2016 and 2017, according to BP data, but fell from 61.3bn m³ in 2011 to 46.4bn m³ in 2015 – a period in which India had access to LNG imports.

On the positive side, this indicates substantial latent demand for gas, but on the negative side the vulnerability of that demand to government policies at both the national and state levels. The existence of import infrastructure does not necessarily translate into actual gas demand.

Pakistan’s circular debt

Similarly, in Pakistan, farmers have been provided with cheap electricity for irrigation as a result of government policies designed to encourage the electrification of water pumping to reduce diesel use and imports.

A lack of cost recovery from electricity generation reduced investment in the sector, leading to insufficient generating capacity and recurrent electricity shortages, alongside high transmission and distribution losses. Low returns from domestic gas production, but the encouragement of gas use, for example in transport, saw demand race ahead of supply.

The lack of cost recovery has resulted in the build up of a huge amount of ‘circular debt’ within Pakistan’s energy sector, estimated by the finance ministry at rupees 473bn ($3.5bn) as of November 20, 2017. This was only half the story; a further debt of rupees 450bn was held by the state-owned Power Holding Private Ltd.

The transition from HSFO to LNG in power generation will certainly improve air quality, but, while likely to prove cheaper in the long-run, does not address the debt issue nor the lack of electricity cost recovery. LNG importers are stepping into the uncomfortable shoes of the fuel oil importers.

Bumpy ride

The root of the problem in both countries is the lack of cost recovery in key gas consuming industries such as power generation and fertiliser production. In both, fundamental reform of subsidy systems which benefit rural communities has for decades been tantamount to political suicide.

Neither India nor Pakistan has undergone rural-urban migration on the huge scale seen in China, one of the many impacts of which was to change the balance of power between rural and urban political constituencies.

India and Pakistan are without question the newest and brightest jewels in the LNG crown, but importers should be wary of some of the more ebullient forecasts – not necessarily in terms of volume, but the speed with which those volumes will be achieved. Importers are likely to need deep pockets, patience and resilience to build and sustain a presence in these markets.