Covid-19 could boost Central Asian plans to access South Asian gas markets [LNG Condensed]

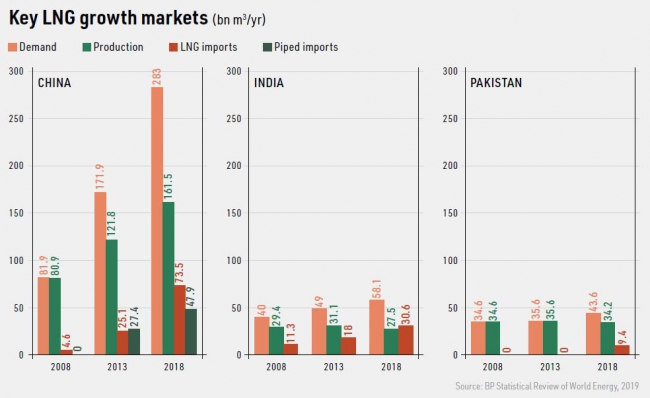

The future level of Asian LNG imports will be determined by many factors, among them the growth and composition of economic activity, the fortunes of coal, renewable energy, nuclear power and indigenous gas production. But for several key importers one of the main factors will be how much piped gas they buy from Central Asia.

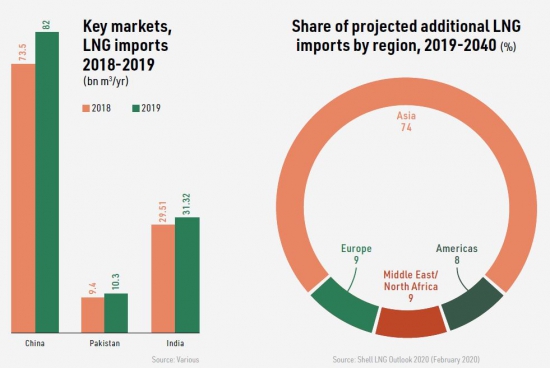

These importers include China, India and Pakistan, which together accounted for less than 7% of global LNG imports in 2008, but more than 26% in 2018, according to BP data. The figure was higher still in 2019. Shell’s LNG Outlook 2020 noted that Chinese LNG imports jumped 14% year on year in 2019, while South Asian LNG imports rose 19%, both above the global increase of 12.5%.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

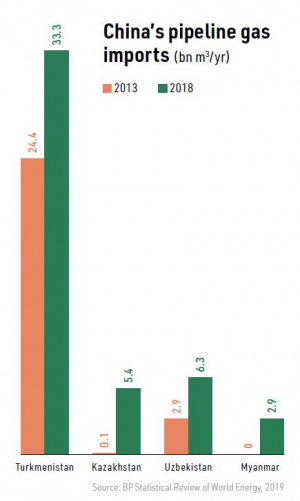

Central Asian pipeline exports effectively mean gas from Turkmenistan, which had 19.5 trillion m3 of proven gas reserves at the end of 2018. This represents about a tenth of the world’s total proved reserves with a reserve to production ratio of 316.8 years. Uzbekistan with 1.2 trillion m3 and Kazakhstan with 1 trillion m3 are among the other Central Asian countries with significant reserves.

TAPI’s potential

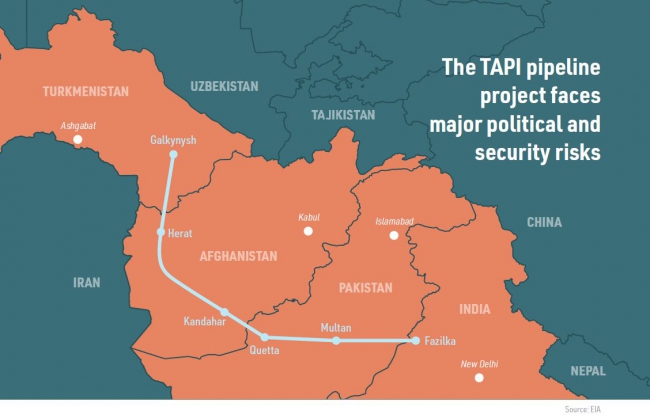

Central Asia already exports large volumes of piped gas and could potentially supply much more, but uncertainty surrounds most of the new projects that could carry this gas to market. This is particularly true of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, which would export gas from Turkmenistan’s giant Galkynysh field to Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

First mooted in 1995, the $10bn project is being developed by the TAPI Pipeline Company Ltd (TPCL), which is 85% owned and largely bankrolled by the state energy company Turkmengaz. The other sponsors are Afghan Gas Enterprise, Pakistan’s Inter State Gas Systems (Pvt) Ltd and Gail India Ltd, each with 5% stakes.

The pipeline would run 214km through Turkmenistan then 816km through Afghanistan, passing the cities of Herat and Kandahar. An 819km section through Pakistan would pass the cities of Quetta and Multan, before the line terminates at Fazilka in India.

Following completion, the capacity of the pipeline would ramp up to 33bn m3/yr, with the gas being supplied over a 30-year period to Afghanistan (5bn m3/yr), Pakistan (14bn m3/yr) and India (14bn m3/yr). However, the completion date for TAPI remains very unclear.

An official presentation about the project was made at a Turkmenistan oil and gas roadshow held in Dubai in February. The event provided little new information, merely repeating previous assertions that construction of the Turkmen and Afghan sections of the line had begun in December 2015 and February 2018, respectively. It added that work on the Pakistan section was due to begin this year.

For instance, in January, a spokesman for the Afghan Mines and Petroleum Ministry was reported by local media as saying that legislation was still needed to acquire land for the Afghan section of the pipeline. He added that only then could construction start on a section of the line that has supposedly been under way since early 2018.

Risk concerns

The delays and opaque status of TAPI have often been attributed to Turkmenistan’s quixotic president, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, and his country’s labyrinthine bureaucracy. However, the main reason for the limited progress on the project is its security and political risks, which have ruled out any recourse to commercial financing.

The security risks relate to the vulnerability of the pipeline to attack, primarily but not exclusively in Afghanistan. The political risks centre on the longstanding tensions between Pakistan and India.

Some mitigation of the security risks was secured in 2018 when the Taliban expressed support for the project. The project got a further boost in late 2019 when TPCL agreed to pay for insurance to cover non-delivery of gas as a result of problems in Afghanistan. And it got another boost at the end of February with the signing of the US-Taliban peace deal.

However, the US-Taliban agreement is only the first step towards a wider peace deal needed to underpin the project’s security. Moreover, political risks related to the mutual distrust between Pakistan and India could prove an even more intractable problem, especially given the current heightened tensions between the two countries over Kashmir and religious issues.

Terminating the project in Pakistan rather than India has been toyed with over the years, but the importance of the 14bn m3/yr of planned sales to India for the overall viability of the project would make this problematic.

Moreover, while the differences between Pakistan and India are profound, they agree on one issue; both believe the price of gas initially agreed with TPCL is too high given the recent fall in LNG prices.

TAPI’s attractions

While TAPI faces severe obstacles and its completion in 2023 appears highly improbable, it still remains attractive to all the participants. It would provide substantial transit revenues plus gas for Afghanistan; diversify Turkmenistan’s sales portfolio; and help Pakistan and India meet their burgeoning gas demand, while providing a counterbalance to LNG imports.

Reaching new markets is a key concern for Turkmenistan since its prospects for exporting gas to Europe through a trans-Caspian pipeline appear increasingly remote, at least in the medium term. Ashgabat is also determined to limit its reliance on exports to Russia and Iran, so TAPI is the only sure way of avoiding over-reliance on China.

This is an issue since China now seems a less staunch partner than appeared the case when the first three pipelines comprising the 1,833km China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline System were commissioned between 2009 and 2014.

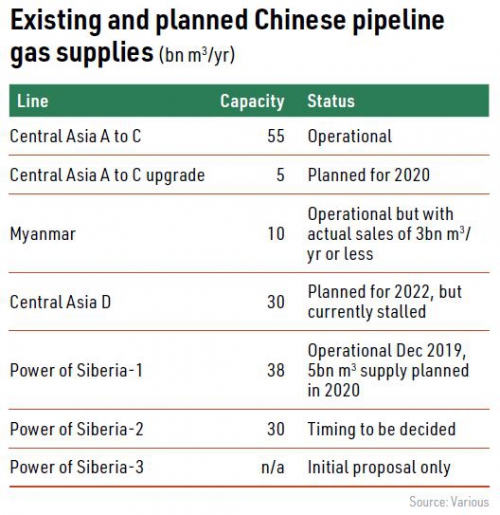

The three lines can deliver 55bn m3/yr of gas from Uzbekistan (10bn m3), Kazakhstan (10bn m3) and Turkmenistan (35bn m3). By February 2020, the pipeline system had delivered more than 300bn m3 of gas, with its deliveries outrunning China’s LNG imports each year from 2012 to 2016.

China’s options

China’s LNG imports overtook piped imports in 2017. Moreover, the latest Chinese gas import pipeline to be commissioned was not the 30bn m3/yr fourth Central Asian pipeline (line D), but the 30bn m3/yr Power of Siberia-1 pipeline from Russia, which entered service in December 2019.

Line D would deliver gas from eastern Turkmenistan to China along a route passing through Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. But Line D is heavily delayed. Originally scheduled to enter operation in 2016, completion is now slated for 2022 at the earliest.

Work on the Tajik section of the line has begun, according to local press reports. However, in 2017, Uzbekistan said it was suspending construction of its section, and has yet to resume work. It also appears that Kyrgyzstan, which postponed the start of construction on its section in late 2019, has yet to begin work.

It has been claimed that one of the main reasons for Line D’s travails is that China wanted to delay receiving additional Central Asian gas. While firm evidence for this claim is lacking, there is no question that China is currently seeking to cut back or defer its existing commitments.

On March 5, China’s biggest single gas importer, PetroChina, issued force majeure notices to its suppliers. Unusually mild winter weather combined with the impact of the Covid-19 outbreak on economic activity had left the listed subsidiary of the state-run China National Petroleum Corporation with overflowing stocks, and a cliff edge approaching in the form of the end of the winter heating season.

PetroChina’s move followed CNOOC’s declaration of force majeure on February 6. However, whereas CNOOC declared force majeure on purchases from three LNG suppliers, PetroChina -- which sources two-fifths of its gas requirements from imports -- sent notices to only one LNG supplier, but all its suppliers of piped gas.

This is not surprising since over two-thirds of PetroChina’s imports are delivered by pipeline. These include a small amount from Myanmar and will in future include gas from the newly-commissioned Power of Siberia-1 pipeline. But most is delivered through the China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline System, which supplied 47.9bn m3 in 2019.

Few recipients of the force majeure notices were prepared to comment. However, Kazakh gas exporter KazTransGas, which had planned to supply 10bn m3 of gas to China this year, said on March 6 that it was discussing future supplies with PetroChina.

Ashgabat’s quandary

None of this suggests that contracted Central Asian exports will not resume once the pandemic ends, nor that Line D will not proceed in the medium term. However, PetroChina’s move has highlighted Turkmenistan’s considerable reliance on China, and is likely to result in the urgent pursuit of sales elsewhere.

With trans-Caspian sales to Europe looking increasingly unlikely, at least in the medium term, and sales to both Russia and Iran increasingly unattractive, that means pressing for sales to South Asia through TAPI. The project may not be done quickly, but the pressure to implement it has ratcheted up several notches.

For LNG suppliers to the burgeoning South Asian market, competition from Central Asian piped gas sales could thus be one of the main long-term consequences of the Covid-19 outbreak.