Country Focus: Turkey: LNG Intake Rises [LNG Condensed]

Turkey’s LNG imports reached a record 11.3bn m3 in 2018, according to official data, up from 5.9bn m3 in 2013. In 2019, a new record was set with imports of 12.69bn m3.

This was despite an overall drop in gas consumption of 9.0% to 44.89bn m3 last year and a fall in total gas imports of 10.2% to 45.21bn m3.

Imports were particularly strong in the first half of the year, reaching a record high of 7.14bn m3, according to the country’s Energy Market Regulatory Authority, with LNG surpassing for the first time a 30% share in total first-half imports of 23.29bn m3. LNG imports were up 14% on the same period a year earlier even though total gas imports were down 10%.

In particular, Turkish imports of US LNG leapt 463% in the first half of 2019 from 191mn m3 in the same period of 2018 to 884mn m3. By contrast, Russian pipeline imports slumped 35.7%.

Diversification strategy

Two main factors have allowed Turkey to favour LNG over Russian pipeline supplies: the availability of low-priced volumes, and the leverage and uncertainty created by Russia’s attempts to circumvent the Ukrainian gas system as a means of getting its gas to European markets.

At the same time, however, Ankara has sought to limit gas use for power generation, depending instead on the cheaper alternative of coal and lignite. Gas use for power generation fell last year by 38.3%, according to official data, from 18.2bn m3 to 11.25bn m3. Having played second fiddle to gas in the power generation sector for years, coal became the largest source of electricity generation for Turkey in 2016 and then by an even greater margin in 2018 and 2019.

This lowest-cost strategy reflects the travails of the Turkish economy, which, having grown by 7.5% in 2017, saw its economic expansion slow to 2.8% in 2018 and zero in 2019. The slowdown has been accompanied by a deterioration in the country’s balance of trade, highlighting its dependence on imported energy. The reduction in power sector gas use in 2018 was a major contributory factor to the improvement in the country’s balance of payments.

Prior to the outbreak of the coronavirus (Covid-19), the World Bank expected a return to growth of about 3% in 2020, but that, as with other GDP forecasts in the current environment, is unlikely now to be realised.

Limited climate ambitions

Turkey has stepped up its deployment of renewable energy sources such as solar and wind to take advantage of their low costs, so that, in 2018, renewables, not including hydropower, generated about 12.5% of the country’s electricity, up from 4.8% in 2014.

However, the growth in coal use means that if Turkey adopts a more aggressive decarbonisation strategy, gas-for-coal displacement would be an obvious pathway to large, short-term gains in greenhouse gas emissions, which should benefit LNG.

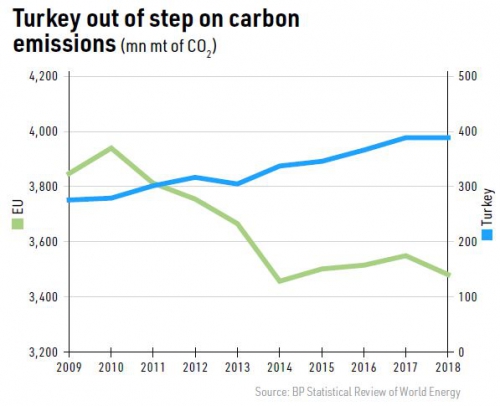

Turkey is out of line with the rest of Europe when it comes to carbon emissions. The country’s carbon emissions have been rising fairly steadily over the last decade from 276mn mt of CO2 in 2009 to 390mn in 2018, in contrast to the EU’s downward trend.

Slow economic growth and sharp hikes in the price of gas supplied by Botas to gas-fired generators have left many of the country’s gas plants idle.

Russian angle

Turkey imports gas by pipeline from Russia via the BlueStream pipeline, which has capacity of 16bn m3 a year and delivers gas under the Black Sea to make landfall in Samsun. In contrast, the Trans Balkan gas pipeline brings gas through Ukraine, Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria before reaching Turkey in the west. Gas coming via the Trans Balkan pipeline is being displaced by gas through the new Turkstream pipeline, which also runs under the Black Sea.

Turkey also imports pipeline gas from Azerbaijan and Iran. Turkey has been taking more Azeri gas as volumes increase through the recently commissioned TransAnatolian Pipeline, but, for Russian gas, Ankara’s purchases have been falling well below contracted volumes with the shortfall made up for by LNG purchases.

Russia’s Gazprom has been unable or unwilling to take a hard line with Turkish state-owned gas importer Botas because of its desire to commission two strings, each with capacity of 15.75nm m3, of Turkstream, which it did in January. Turkstream is the centre piece of Russia’s efforts to circumvent Ukrainian gas transits to south European markets.

Ankara appears to be using LNG and gas from its other pipeline suppliers to pressure Russia into more flexible supply arrangements. If an accommodation can be reached, some restoration of Russian pipeline import volumes is a clear threat to Turkey’s current enthusiasm for LNG, but equally could also be absorbed by an increase in gas use in the power sector.

LNG infrastructure

Turkey has four regasification terminals, the first, Marmara Ereglisi, came on-stream in 1994. It is 100% owned and operated by Botas.

The second, Izmir Aliaga, was commissioned in 2006 and is owned and operated by the privately-held Egegaz, which is part of the Colakoglu Group. Both are onshore terminals.

The country’s first floating, storage and regasification unit (FSRU) was added in 2017 at Etki with the FSRU Neptune and the second in 2018 at Dortyol with the FSRU Challenger. Etki is operated by Etki Liman Isletmeleri Dolgalgaz Ithalat ve Ticaret and Dortyol by Botas. Challenger is the largest FSRU in the world, but is slated to be relocated to Hong Kong in 2021.

According to International Gas Union data, regasification capacities based on nameplate totalled 25mn mt/yr (34bn m3) at end-2018 -- Marmara Ereglisi 7.6, Aliaga 8.0, Etki 5.3 and Dortyol 4.1.

GIGNL, the International Group of Natural Gas Importers, puts total nominal capacity at 16.8mn mt/yr (Marmara Ereglisi 4.6, Aliaga 4.4, Etki 3.7 and Dortyol 4.1).

Gas Infrastructure Europe comes in at about 18mn mt/yr, with expansion plans of 2mn mt/yr at Aliaga and 2.7mn mt/yr at Marmara Ereglisi.

A third FSRU is planned for the Gulf of Saros in the Aegean with capacity of 3.8-7.6mn mt/yr.

Botas has a long-term contract with Algeria’s Sonatrach for 3.02 mn mt/yr, which was raised in 2018 to 3.21 mn mt/yr, with the expiry date pushed back to 2024. Botas also receives 0.91 mn mt/yr from Nigeria LNG, a contract which expires in 2021.

Turkey’s gas storage capacity is expected to rise from about 3.4bn m3 now to over 11bn m3 by 2023, constituting more than 20% of the country’s annual demand.

As a result, the infrastructure to import more LNG and consume more gas in the power sector is all in place, as, increasingly, are the major pipelines for Turkey to take up its longstanding ambition to be a major gas transit country. This all points to the emergence of an increasingly competitive market for gas imports into the country, one in which LNG will have a long-term role, even if future volumes depend heavily on Russian imports and Turkish power

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)