Country focus: Italy [LNG Condensed]

Gas burn in Italy should rise as a result of the 2025 phase out of coal-fired generation, which last year still accounted for just over 10% of electricity supply. Moreover, the country’s expansion of renewable energy sources is decidedly slow. However, with the long-in-gestation Trans-Adriatic Pipeline soon to come on-stream, Italy’s gas import mix remains uncertain. Its LNG terminals last year ramped up to near full capacity, presenting a fundamental obstacle to maximising further the opportunity presented by cheap LNG.

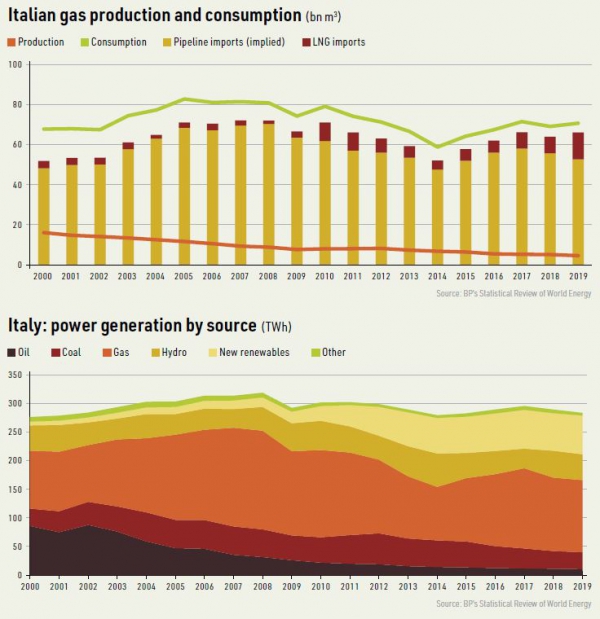

At 40% Italy has the highest ratio of gas use as a proportion of primary energy supply in Europe, and, despite demand last year being 15% below peak use in 2005, the country is increasingly dependent on gas imports.

Italy’s domestic gas production, which has never been large, amounted last year to just 4.6bn m3, roughly a quarter of production in 2000. There appears to be little chance of a major revival, although domestic output may increase as a result of increased biomethane production.

Snam scenarios

In its 2017-2035 ten-year development forecast, Italian gas grid operator Snam outlined both high and low demand forecasts.

In the low-case scenario, Snam sees a mild decline in gas use (natural gas and biomethane) to 65.7bn m3 in 2035, with domestic production low at 4bn m3. Gross imports rise to 73bn m3 in 2026 and 2030 before falling to 69.8bn m3 in 2035. Net imports fall from 64.8bn m3 in 2016 to 61.7bn m3 in 2035.

In the high-case scenario, gas demand rises to 83.5bn m3 in 2035, of which 13.1bn m3 are met by domestic supply, owing to much higher biomethane production (10.4bn m3). Gross imports peak at 76.8bn m3 in 2030 and dip slightly to 75.5bn m3 in 2035. Net imports rise to 70bn m3 in 2026, 71.7bn m3 in 2030 and then fall slightly to 70.4bn m3 in 2035.

The scenario assumes considerable growth in gas use in transport, where Italy already has a substantial base. Italy had, in 2019, 1.13mn natural gas-fuelled vehicles (NGVs), the highest number in Europe, and, at the end of March 2019, had 1,326 compressed natural gas fuelling-stations, according to industry group NGV Europe. This puts it seventh in terms of NGVs globally.

In the high-case scenario, gas is seen as a partner to renewables in achieving emissions targets, while also providing back-up and flexibility for power generation. Biomethane is the primary means of limiting emissions growth from higher gas use.

Imports

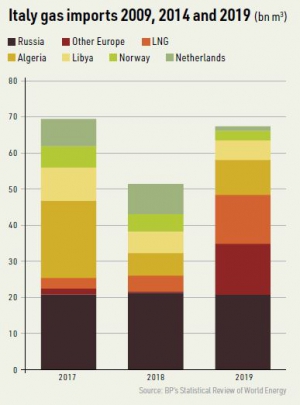

Italy has a robust system of import pipelines from multiple sources, including both Algeria and Libya, but it has seen large changes in the composition of those imports over the last decade.

Notably its consumption of gas from the Netherlands has fallen sharply, in part most recently owing to lower Dutch output as a result of the decline of the Groningen gas field. Dutch gas imports to Italy dropped from 7.5bn m3 in 2009 to 1.2bn m3 in 2019.

Similarly, its offtake of Norwegian gas dropped from 5.9b m3 in 2009 to 2.7bn m3 in 2019. Algerian and Libyan gas imports are also sharply down falling from 21.4bn m3 and 9.2bn m3 respectively in 2009 to 9.7bn m3 and 5.4bn m3 last year.

The shortfall has largely been met by increases in re-routed Russian gas supply, which, in the BP data shown, is evident in the rise in the ‘other Europe’ category, and more latterly by the jump in LNG imports.

TAP imminent

However, Italy is again set to increase its pipeline import capacity and supply source options. The TransAdriatic Pipeline (TAP) operating company said in June that it had completed the 105-km offshore section of the pipeline under the Adriatic Sea.

TAP project director John Haynes said the whole project is now more than 95% complete and the company looked forward to crossing the finish line by the end of this year.

The 878-km TAP plans to starting pumping gas to southern Europe in the autumn. Its phase 1 transport capacity is 10bn m3/yr of Azeri Shah Deniz stage 2 gas, but it is able to double its capacity to 20bn m3/yr, for which other gas suppliers will be able to bid.

However, it has pushed back the binding bidding phase of the market test for additional capacity from January next year to July, saying that market conditions were unfavourable and the operators of TAP and the grid operators at either end of the line, Snam in Italy and Desfa in Greece, wanted more time.

It remains possible that some of TAP’s future gas volumes come from Russia, but whether Azeri or Russian, the gas travels a long way before making landfall in Italy. The ‘unfavourable market conditions’ cited by the pipeline company no doubt reflect the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, but also the competitive price of LNG.

LNG capacity limits

Despite a multitude of proposals over the years for more, Italy has only three LNG terminals. The first, Panigaglia LNG, was completed in 1971 with import capacity of 2.5mn mt/yr. Adriatic LNG was completed in 2009, with capacity of 5.8mn mt/yr, while the third, the Toscana Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU), was installed in 2013 with capacity of 2.7mn mt/yr.

This totals 11mn mt/y or about 15bn m3, based on International Gas Union data, which means last year the country’s LNG terminals were working close to full capacity. Although Italy may be receiving some regasified LNG as part of its northern imports, to take further advantage of the low cost of LNG, it needs more LNG import capacity.

Three projects, totalling 24bn m3 of capacity, have authorisations from the ministry of economic development, but none are listed as under construction, although a small-scale LNG terminal on the island of Sardinia is nearing completion.

Gas burn

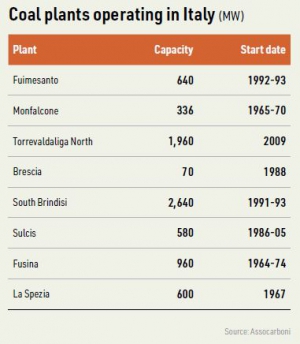

An important element of Italy’s future gas consumption are impending changes in the Italian power generation sector. In November 2017, the government took the decision to phase out coal-fired generation by 2025, but the process is taking place more slowly than in some other European countries with similar targets.

Italy has eight coal-fired plants in operation, with total capacity of 7.8 GW, according to Italy’s coal association, Assocarboni. Although substantially down from over 50 TWh of generation in 2010 to 29.7 TWh last year, this still represents just over 10% of the country’s electricity supply, a substantial chunk which will need to be sourced from alternative technologies as the phase-out progresses.

However, Italy’s increase in generation from new renewable energy sources is far from exponential and, in fact, according to BP data, renewable generation was no higher last year than in 2017, despite increases in capacity. Italy has only been adding around 0.5 GW/year of wind capacity since 2016 and it is all onshore; the country does not have the offshore wind resources of northern Europe.

The country does have a good solar resource, especially in the south, but solar produces much less power per MW installed than wind and, in any case, Italy’s rate of solar installation is also sluggish at substantially less than 1 GW/year since 2013.

Limited renewables growth combined with the coal phase out imply higher gas burn, but the degree to which LNG is a beneficiary depends not just on price, but whether the country can fast-track new LNG import capacity.

_f650x419_1596458661.JPG)