Country Focus: Brazil Locking In LNG Demand

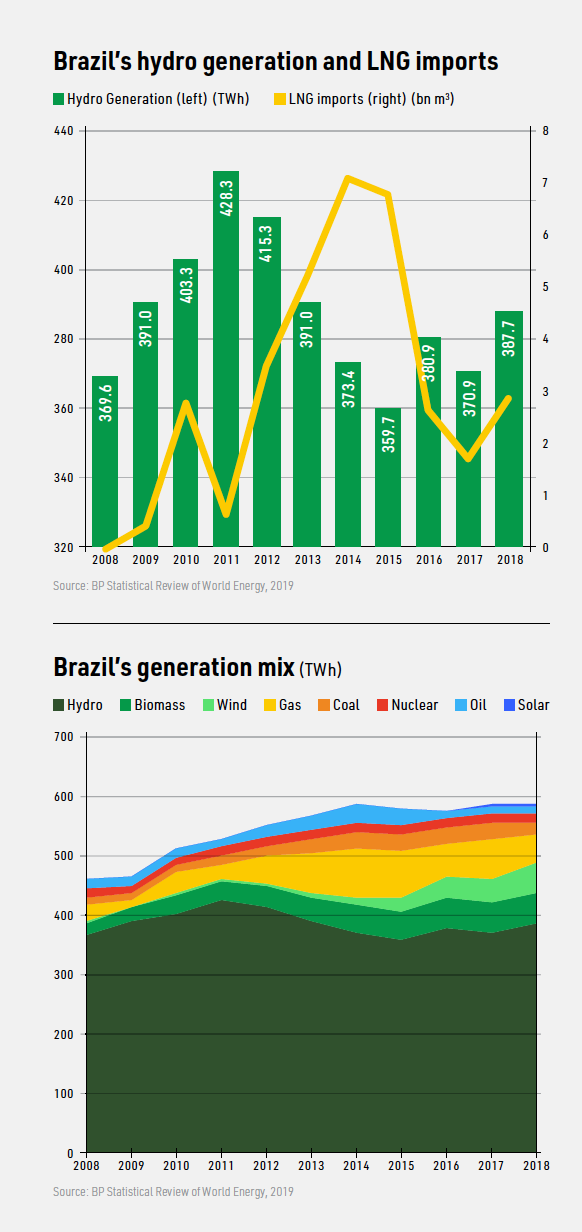

Brazil started importing LNG in 2009 and its appetite for the fuel has proven volatile. It rose strongly to a peak of 7.1bn m3 in 2014, before declining to 6.8bn m3 in 2015, falling sharply thereafter. In 2017, it was just 1.7bn m3 before rebounding last year to 2.9bn m3.

The country has three LNG terminals, all floating, but they are currently served by only two Floating Storage and Regasification Units (Fsru). Pecem in the north and Guanabara Bay in the south both came on-stream in 2009, while a third, Bahia, was added in 2014, according to International Gas Union data.

All three are 100% owned by state oil and gas company Petrobras, which ended its contract for the 1.8mn mt/yr Fsru Golar Spirit in 2017. The two active Fsrus are the 3.8mn mt/yr Golar Winter, which is currently operating at Pecem, and Excelerate Energy’s 6.0mn mt/yr Experience in Guanabara Bay.

GAS TO BE MORE THAN A BACK-UP

GAS TO BE MORE THAN A BACK-UP

Brazil’s two operational LNG terminals are heavily under-utilised. The country has typically bought LNG on a spot or short-term seasonal basis to support gas-for-power generation in an electricity system dominated by hydro power.

Peak LNG imports in 2014 and 2015 reflected a sustained period of low rainfall, which left reservoir levels low. However, even in 2017 and 2018, hydro generation was again relatively low, but LNG imports did not recover to previous levels.

This reflected two factors: first increased domestic gas availability, largely associated with the development of the country’s huge pre-salt oil reserves; and second, the expansion of renewable energy, notably wind and biomass in the form of bagasse, the sugar cane by-product of the country’s ethanol and sugar industries.

Given these factors, the trajectory of Brazil’s LNG imports appeared to be heading towards zero, with just the occasional seasonal spot purchase. Expectations were also raised that, like Argentina, the country’s long term future was as an LNG exporter rather than importer.

The director-general of the oil and gas regulator ANP, Decio Oddone, stated last year: “LNG shall be used as a bridge until domestic natural gas is available. In the future, natural gas abundance can turn Brazil into an LNG exporter.”

NEW LNG TERMINALS

Yet new LNG import terminals are being built. According to a recent study by federal energy planning company EPE, there are at least 23 projects at different stages of development for new LNG terminals in Brazil, two of which are under construction.

Celse, a joint venture between Golar Power and EBrasil is building a floating regasification terminal at Barro dos Coqueiros in Sergipe state. It is an LNG-to-power project, which will serve a 1.5 GW gas-fired power plant, which is expected to be complete in January 2020. The Fsru Golar Nanook, which has capacity of 21mn m3/d hooked-up with the terminal in March this year.

The second project under construction is Gas Natural Acu, which is a joint venture between Prumo Logistica, BP and Siemens. In 2018, Prumo Global Logistics contracted with BP for the supply of 0.7mn mt/yr LNG for 25 years starting from 2023. The project in Rio de Janeiro state will use the Fsru BW Magna to deliver 21mn m3/day of gas. The BW Magna is expected to arrive in 2020.

The terminal will be used to supply gas to new gas-fired plants, UTE GNA I and II, which will have generating capacities of 1.3 GW and 1.6 GW respectively, coming online in 2021 and 2023.

PDE 2027

The reason for developers’ enthusiasm is the direction taken by the country’s long-term energy planners under Bolsanaro as laid out in the 2027 energy plan (PDE 2027), which was approved last December. This plan, which has come under heavy criticism from environmental non-governmental organisations, gives an important role to both coal and gas in electricity generation, and also, significantly, places limits on the development of competing renewable energy sources.

The PDE, which assumes relatively high GDP growth of 2.8% a year on average, calls for the addition of 17 GW of new gas-fired power plant over the forecast period to 2027.

In the country’s A-6 auction for new generating capacity, which will be held October 17, 52 gas-fired power plant projects were registered, equalling 42.7 GW of capacity, alongside 29 GW of solar PV and 26 GW of wind. The winners, which are for plant to be in service within six years, will be awarded long-term power purchase agreements.

Under the PDE 2027, a minimum of 1 GW a year of new solar is required, but there is also a ceiling of 2 GW a year. Wind will also face an annual 2 GW ceiling from 2023. The result is likely to be a sharp rise in the proportion of gas-fired generation in the electricity mix.

GAS BALANCE

Yet even with this more positive outlook for gas-fired generation, it is by no means clear that Brazil will necessarily need LNG imports.

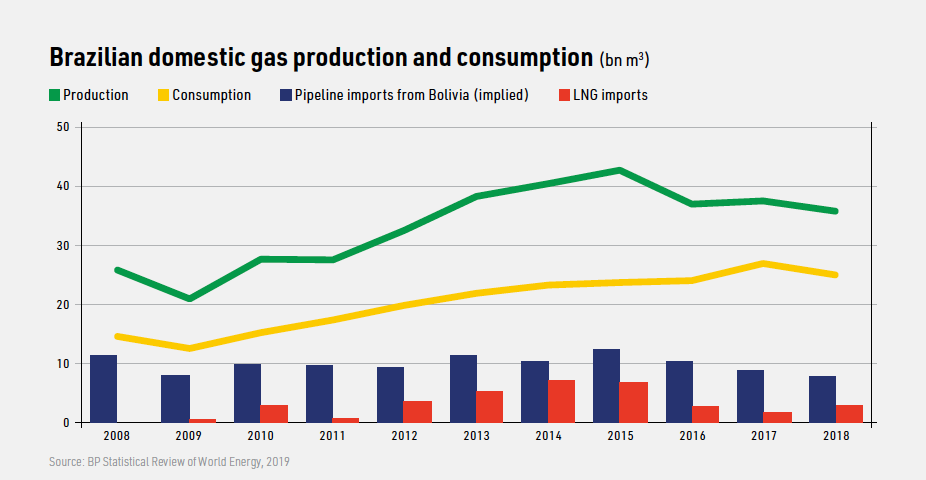

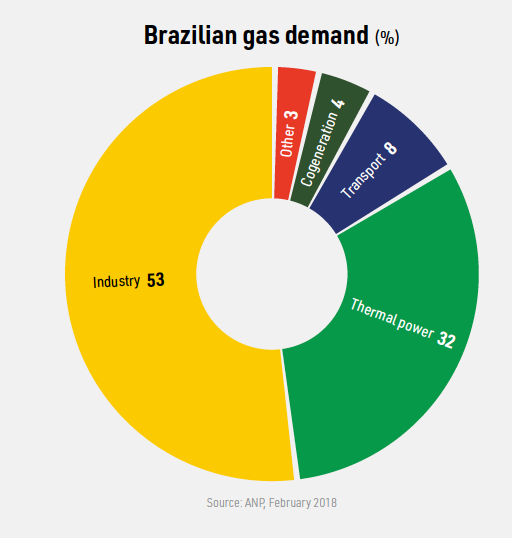

Although industry accounts for 53% of Brazilian gas demand, thermal power consumption at 32% is the most volatile element. As of February last year, transport accounted for a further 8% of gas demand and cogeneration 4%. Although gas production fell in 2018, it has been on a rising trend, boosted by associated gas from the development of the country’s pre-salt oil reserves.

According to ANP, just over half of Brazil’s domestic gas is associated gas, while 30% comes from conventional offshore production and 19% from conventional onshore, with the majority of total supply produced off the states of Rio de Janeiro (50%) and Sao Paulo (18%).

The under-utilised 11bn m3 year Gasbol pipeline also brings gas from Bolivia into Sao Paulo state, which is Brazil’s industrial heartland. Brazil imported 7.6bn m3 of gas from Bolivia last year.

PRE-SALT GAS

Pre-salt oil development has proved slower than forecast not least because of the corruption scandals that have rocked Brazil in recent years, which have impacted Petrobras. Moreover, while overall development has been slower than expected, bringing associated gas onshore to compete in the domestic market has lagged behind oil production.

The ANP says pre-salt gas production has boosted output by 90% between 2008 and 2018 and in total the country produced 40.1bn m3 in 2018, more than total domestic gas sales of 27.7bn m3.

However, the lack of infrastructure to bring the associated gas onshore has meant a sharp rise in offshore reinjection into oil wells, leaving the domestic market short of gas, resulting in a continued reliance on imports. In 2017, 30% of Brazil’s total gas production was reinjected, 12% consumed on oil and gas platforms and 3% flared or vented, according to ANP.

The ANP expects Brazilian oil production to rise from 2.58 million b/d in 2018 to 7.5 million b/d by 2030. EPE expects domestic gas supply available to the market to grow from 23.7bn m3 in 2017 to 40.5bn m3 in 2027.

Projections for Brazilian oil production have regularly disappointed, but there are clear signs that output is now on a steadier upward trend as more Floating Production Storage and Offloading vessels go into service on the pre-salt fields.

In its September oil market report, the International Energy Agency reported a large rise in total oil production of 420,000 b/d for Brazil in August to 3.05mn b/d.

BRINGING GAS TO SHORE

The key issue for the country’s gas balance is how much of and how quickly the additional associated pre-salt gas can be brought to shore and fed into the domestic gas system. It is this issue which has delayed an agreement over the future import of Bolivian gas via Gasbol, the long-term contract for which expires at the end of this year.

The growth of Argentinean gas supply, as a result of development of the Vaca Muerta shale play, is an additional factor, as this could provide another source of imports to compete with LNG.

However, Oddone has stated that he sees Argentinean gas coming to Brazil as LNG. Rather than develop pipelines, LNG infrastructure gives both countries flexibility in being able to sell to and buy from multiple markets.

As a result, on its current trajectory, Brazil looks likely to lock LNG-to-power supply chains into its electricity market protected by long-term contracts. If the gas balance becomes positive, Brazil could emerge as both an importer and exporter of LNG.