Colombia eyes second terminal [NGW Magazine]

In its efforts to avoid what could an imminent gas crisis, the Colombian government has rediscovered its enthusiasm for its Pacific LNG importing terminal. The project could offset the domestic gas deficit, as natural gas reserves dwindle in the country.

On June 30, the energy mining and planning unit (UPME, the part of the mining and energy ministry responsible for infrastructure planning), relaunched a bidding process to design, construct and operate a new LNG facility and a pipeline in Buenaventura, on the Colombian Pacific Coast.

The South American country commissioned its first LNG terminal on its Caribbean coast in December 2016. It is a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) located in Baru, Cartagena de Indias. With 400mn ft³ /d (8.5bn m³/yr) of regasification capacity and 170,000 m³ storage capacity, the FSRU, operated by Sociedad Portuaria El Cayao (SPEC GNL), supplies regasified LNG to three thermal power stations in Colombia.

Although two thirds of the national power generation mix is hydro, the country’s rainfall is not as dependable as it once was, and its gas reserves are in decline. The government is therefore looking at more LNG in a new part of the country.

But the plan is not popular everywhere: its opponents say that if more gas is needed, the government should prioritise domestic production instead of buying what may become expensive imports.

Looming gas shortage

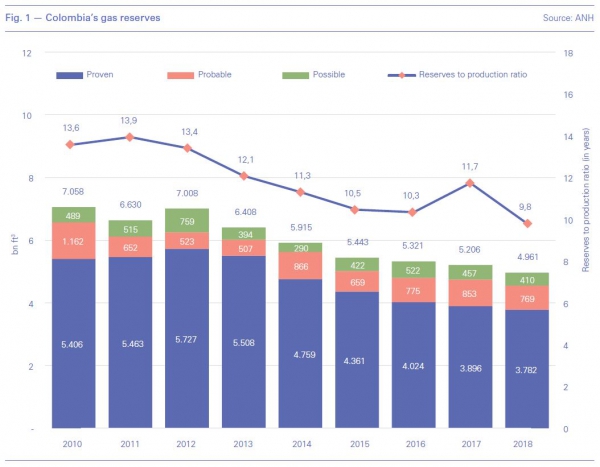

According to official figures, Colombian proven gas reserves will last for about eight years but as they taper off, shortages will be possible by 2024, affecting power generation and industrial demand.

Under this scenario, UPME has concluded that to secure the natural gas supply and its reliability as a public service over the next 10 years, the Colombian system will need to reinforce the midstream infrastructure by including an importing facility and new pipeline for natural gas transportation on the Pacific coast.

Pacific LNG import Terminal

An LNG regasification terminal in Buenaventura in the southwest and a 30-in pipeline around 100 km long, will cost about $700mn.

Though the primary purpose of the new facility is to offset a gas shortfall in the coming years, it has gained some detractors in the local industry who claim that the Colombian government has not given priority or support to local gas producers to develop national reserves.

NGW discussed the benefits associated with new LNG infrastructure with lawyer Monica Torres, the CEO of Viable Legal Business. She was one of the lawyers involved in the bidding process for the Cartagena terminal.

Some studies have claimed that there are important conventional and unconventional gas resources both on and offshore, which has opened the debate in the local gas industry over the real need for a new importing facility.

However, as Torres explained, a gas shortage crisis is expected in the short-term, while it takes some time to bring new discoveries to market, so time is of the essence. Even though the Colombian government started assigning exploration contracts last year, it could take at least six years for gas to reach the market – or seven in the case of offshore reserves. Unconventional gas production using hydraulic fracturing remains prohibited.

Delays in the LNG Pacific Terminal

Since 2018, the Colombian government has seen the Pacific terminal as an alternative to avert the gas shortfall. But as Torres explained, the first element has been based on expectations over the potential increase in natural gas domestic production.

Expectations have and continue to hold back the project, she added. Even though domestic natural production could potentially increase in the future, Colombia cannot afford to wait in the short term. The LNG import infrastructure in the Colombian Pacific has more than two years' delay and this delay has been due to those expectations, she said.

The second factor of delay perhaps has been to set a new regulation, she indicated. Torres stressed that for the Pacific LNG terminal, the Colombian government has had to establish a commercial and legal framework completely different from the Caribbean terminal.

She explained that the Cartagena regasification project emerged as a solution to fuel supply problems for the three thermal plants in the Colombian Caribbean, and the main driver was to replace expensive and polluting liquid fuels such as diesel with gas. The Pacific infrastructure, on the other hand, is intended to promote new sources of gas in the country, as reserves will not be sufficient to secure the constantly growing demand.

Benefits, opportunities, and challenges of the new terminal

Torres highlighted that the Pacific terminal is considered a public interest project, which means it enjoys different regulations and tariffs than the Caribbean terminal.

The new terminal will not only consider national gas demand but also will aim to meet its continuing growth, supporting power generation in periods when hydroelectricity output is not sufficient and create new supply for industries and local communities, which now have access only to the most expensive natural gas in the country.

Besides, with the LNG regasification terminal operating, there is the opportunity to distribute gas by truck, reaching a higher number of users who today do not have access to natural gas, she added.

In terms of jobs, it is expected that during the phases of constructing, operating, and maintaining, the new terminal will benefit the economy of southwestern Colombia.

Investors will receive a regulated income, which will be paid mainly by regulated demand (small consumers) through the natural gas service rate, Torres said. There is a draft resolution under which the regulator has proposed a mechanism to alleviate the payment burden that otherwise would fall on small consumers, and gives access to the competitive market, such as power generators and industry. They might also receive contracts granting access to the terminal, helping to underpin the costs.

However, Torres mentioned that the project could also face some environmental challenges. The area in which the project would take place not only involves protected areas for environmental reasons but involves indigenous territories and ethnic groups and probably some difficulties due to the terrain.

To start the building phase, the bidder must have an environmental licence, issued by the environment regulator. Moreover, if the pipeline route affects the enjoyment by the indigenous people of their land, the bidder must go through a consultation process that will ensure the protection of those groups’ fundamental rights. So there is no guarantee that an environmental licence will be granted and in any case it could force a delay to the planned date for starting operations.

According to the new timetable, which expects to see commercial operations of the project in 2024, the deadline to release the final bidding documents was scheduled on July 30. But as the health crisis has hit the country, the documents have not yet been released.

Torres said that there are many investors interested in the project and this is a positive indication concerning the bidding process. It is due to start in the first quarter of next year, according to the authorities' announcement.