Coal’s staying power in Asia [Gas in Transition]

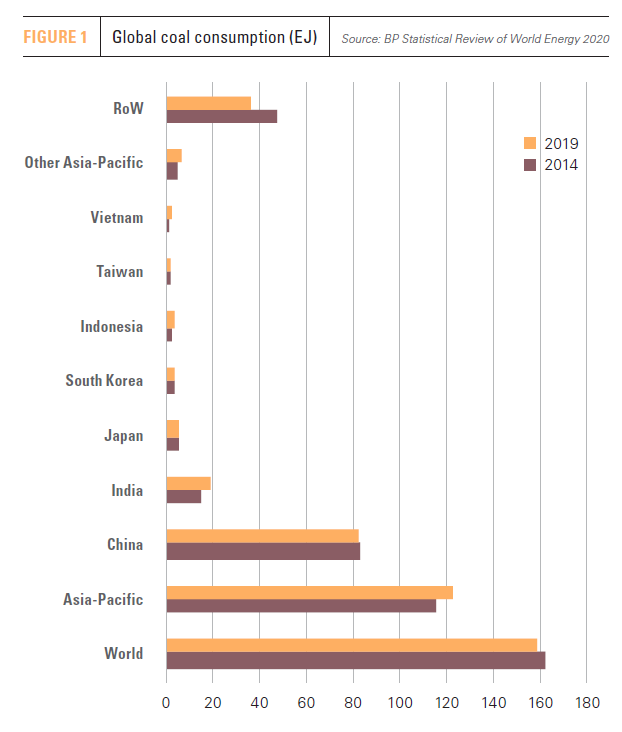

Trends in the second half of the 2010s did appear to support the expectation that global coal demand was set for an inexorable decline. Demand peaked in 2014 and declined thereafter, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

The decline accelerated sharply in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Global Energy Review 2021, coal demand fell last year by 220 million metric tons of coal equivalent, or almost 4% year on year.

The IEA noted that the electricity sector accounted for more than 40% of “the biggest drop since World War II” in the use of the fuel. Coal-fired electrical output fell by 440 TWh, or 4.4% year on year in 2020. The IEA observed that coal had been “squeezed in the power mix by lower electricity demand, increasing output from renewables, and low gas prices.”

Much of the decline occurred in the US and EU, with the IEA noting that power station coal use fell by 20% in the former and 21% in the latter. The decline in Asia was less pronounced.

Asia’s different path

This regional difference had already become apparent in the second half of the 2010s. While coal use fell globally between 2014 and 2019, the BP Statistical Review noted that it grew by more than 6% in Asia-Pacific (Figure 1). And it grew faster still in some countries within the region. For instance, in Vietnam, coal demand almost tripled between 2014 and 2019.

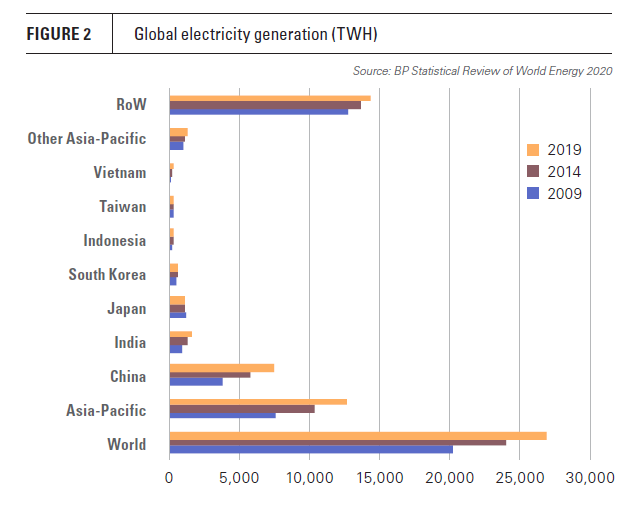

Much of the growth occurred in the Asian electricity sector, which is growing at a faster rate than the global average and is more dependent on coal. Asia’s share of world power generation (Figure 2) rose from 37% in 2009 to 47% in 2019, while in the latter year coal accounted for 58.1% of total generation in Asia-Pacific compared to only 36.4% in the world as a whole.

These regional differences are expected to become even more pronounced this year. The IEA projects that global economy activity, energy consumption and electricity demand will grow in 2021 by 6.0%, 4.6% and 4.5%, respectively. It added that global coal demand will grow by 4.5%, with more than 80% of the growth occurring in Asia and more than 75% in the coal-fired generation sector, where global output is projected to rise year on year by 480 TWh.

The IEA projected that China alone will account for more than half the growth in world coal demand in 2021. This is despite the country’s massive investment in renewables. China is forecast to generate over 900 TWh from solar and wind capacity in 2021, meaning coal will account for only 45% of the projected 8% increase in electricity output.

The IEA also projected that coal demand will grow outside Asia in 2021 as a result of rebounding economic activity. But it forecast that the fuel will claw back only a quarter of the sales it lost in advanced economies in 2020, with coal’s recovery “curtailed by renewables deployment, lower gas prices and phase-out policies.”

Preconditions for coal’s replacement

It does seem likely that coal will experience severe decline in most advanced economies, being replaced predominantly by renewables and gas. Relatively low GDP growth and a shift to less energy-intensive economic activity will both suppress energy demand growth and result in more energy being supplied as electricity.

The replacement of coal by gas will also be facilitated by the fact that many of these economies have large amounts of gas-fired capacity, well-developed gas infrastructure, various gas supply options, and market-based gas pricing policies. In addition, many of them plan to implement smart grids and emissions reduction policies. This applies equally to advanced economies in Asia, such as Japan and South Korea.

However, the position in most of Asia is very different. Strong growth in energy and electricity demand is expected, based on robust growth in often energy-intensive sectors of the economy. Gas-fired generating capacity is often limited. So too is the development of gas delivery infrastructure and regulatory structures, and the availability of diversified and competitive gas supplies. At the same time, in many developing Asian countries the potential for deploying renewables or nuclear power is limited by geographic, technical or financial factors.

However much their governments and populations may want to reduce emissions and other environmental problems, the replacement of coal could thus prove problematic.

In some cases, this reflects the fact that coal has been the dominant source of power generation for decades, with few signs that change is in the offing. China is the most obvious example, with a strong lobby arguing that continued large-scale coal use is necessary to maintain a reasonable level of energy self-sufficiency. Consumption reached more than 4bn mt in 2020, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, while the country’s National Coal Association has said demand could reach 4.2bn mt in 2025.

An old fuel in new plants

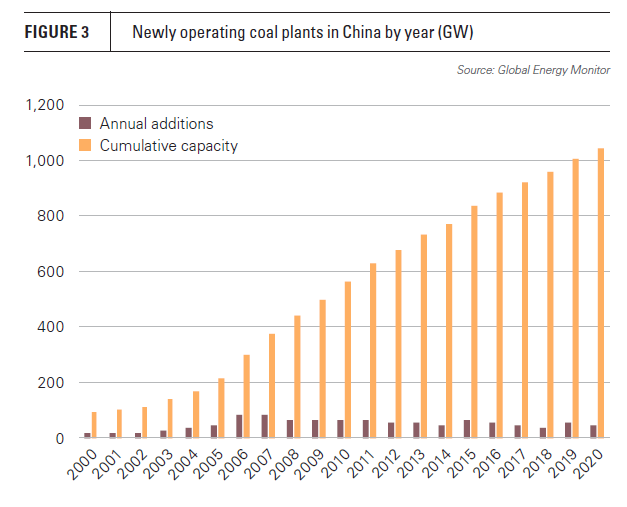

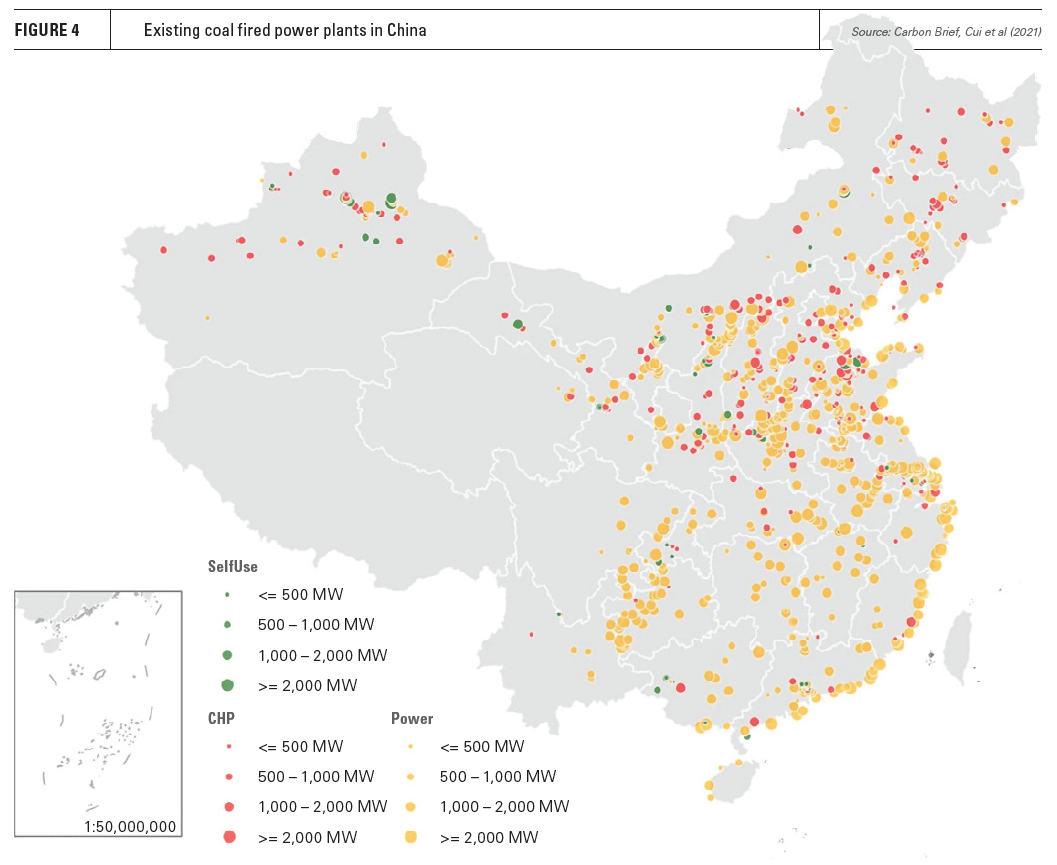

A large percentage of Chinese coal is used for power generation, with most being burnt in relatively new plants that could have up to five decades of remaining life. According to Global Energy Monitor’s (GEM) global coal plant tracker, China had 1,043 GW of operating capacity in 2020, of which 505 GW was installed between 2010 and 2019.

Nor has the installation of new coal-fired plant ended, despite this being regarded as one of the main measures needed if Beijing is to achieve its policy of reversing emissions growth before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. Over 38 GW of coal-fired plant was commissioned in 2020, according to GEM (Figure 3), while another 73 GW was reported to have entered the project development process.

The rapid replacement of coal will be problematic not only for longstanding coal generators such as China and India, but also for countries where its use is more recent. This is especially the case in those countries in Southeast and South Asia where the shift to coal was driven in part by the desire to reduce gas use in power generation.

The shift was pursued for various reasons. For instance, in Malaysia and Thailand, investment in coal-fired plants was intended to mitigate concerns over security of supply and excessive dependence on gas-fired generation. In Vietnam, it was largely down to the lack of sufficient additional indigenous gas to meet the rapid projected growth in electricity demand. This was also a factor in Indonesia, where the use of low-cost indigenous coal for power generation was in part intended to allow the sale of gas production to higher-value markets, including gas exports.

Key opportunities for gas

These factors mean a rapid shift from coal to gas in much of the Asian power generation sector is unlikely. But that is far from saying that Asian gas demand growth will be muted.

The IEA has projected that global gas demand will increase by 3.2% in 2021, driven by increasing consumption in Asia, the Middle East and Russia. However, it added that “nearly three-quarters of the global demand growth in 2021 is from the industry and buildings sectors, while electricity generation from natural gas remains below 2019 levels.”

This is the case in China, where the burgeoning city gas market offers not only considerable opportunities, but better returns than the power sector. Much of the growth in Chinese gas use in the second half of the 2010s came from the conversion of coal-fired heating systems in northern cities, with more conversion projects planned in the commercial and industrial as well as residential sectors. By contrast, the relative cost and availability of coal and gas means gas-fired generation is not currently competitive in much of China, with a large part of the country’s 97 GW of gas-fired capacity only operating at peak times, if then.

That is not to say that China and other countries in a similar position offer no scope for competitive gas-fired generation. For instance, gas-fired generating plants at coastal sites can play a key role in kick-starting the rollout of city gas networks and acting as the anchor customers for LNG import terminals. Moreover, gas-fired generation could surge if carbon pricing or other measures to reverse its competitive disadvantage are introduced.

But even then, the replacement of more than a small part of Asia’s coal-fired generating fleet in the near to medium term is unrealistic, not least in terms of gas availability

It is certain Asia will see substantial growth in gas-fired and renewable output, with constraints to their inroads being reduced where accompanied by investment in smart grids and electricity storage capacity. But the sheer scale of coal’s contribution to Asia’s electricity requirements – 72% of operational coal-fired capacity is in Asia as is 93.5% of the coal-fired capacity under construction – means coal will be central to the region’s power generation for decades to come.