China’s gas challenges [NGW Magazine]

This year China’s natural gas demand has been experiencing rapid and challenging change. Whether driven by economic factors or energy supply security, during the last few months the rapidly-growing gas demand has become a thing of the past.

China’s National Energy Administration (NEA) and the State Council Development Research Center issued a natural gas development report on August 31 that raises a number of interesting issues on the future of natural gas in China.

The rampant growth in natural gas consumption experienced during the last two years has slowed down significantly this year, from 17.5% in 2018 to about 10% in 2019. Total gas consumption is expected to reach 310 bn m3 by the end of the year, in line with SIA’s forecast (Figure 1).

.png)

Even though China’s gas demand is projected to continue growing to 2050, there are increasing uncertainties, and security concerns, regarding its reliance on LNG imports. China relied on imports for 44.5% of its gas consumption in 2018, in comparison to 30% in 2015, and import dependency is growing rapidly – with most of it in LNG.

However, gas imports are being affected by the global economic slowdown and the slower growth in China’s economy – it is experiencing its slowest economic growth in close to 30 years. This is impacting LNG in particular: “LNG is…competing against other energy sources, and it is so expensive that the country’s largest importer loses money selling the fuel,” Nikos Tsafos, senior fellow in the Energy and National Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in a November blog post.

Also key to this is that China’s gas demand growth appears to be affected by the increasingly acrimonious, and prolonged, trade war with the US. This, and the impact of sanctions on Iran, are making China conscious that it is not immune to US policy and that there are risks to relying on other countries for its energy. In response to this China has been re-evaluating import dependency and energy security. As a result of this, it has been reducing dependence on gas imports, putting more emphasis on domestic energy resources, including shale gas but also coal and renewables.

This is also what President Xi Jinping called for in August 2018: a boost in China’s national energy security. In response, CNPC and CNOOC confirmed fast-tracking domestic gas production and infrastructure investments.

In the context of all these developments, the launch of the ‘Power of Siberia’ gas pipeline on December 2 (NGW Vol 4, #23) has come at the right time. This is helping cement the growing China-Russia relationship by adding to China’s energy security, while also providing Russia with access to a potentially enormous gas market, likely at the expense of LNG imports.

China’s gas development

In response to the drive to reduce reliance on imports, the NEA report has specifically called for increased efforts to boost domestic gas production from unconventional sources such as shale gas. Key to this are the Sichuan and Ordos basins (Figure 2), as well as offshore prospects. The NEA report specifically called for developing the Sichuan basin into the country’s top gas hub.

.png)

Zhao Wenzhi, president of PetroChina Exploration and Production Institute, forecasts that China could produce as much as 280bn m³/yr shale gas by 2035. This could constitute 23% of the country’s total gas output by then.

But there is a long way to reach that. Last year China produced just under 11bn m³, which was only 7% of its total gas production of 161 bn m3.

However, CNPC announced September 30 new shale gas discoveries at two new blocks in the Sichuan Basin with a total of about 740bn m³ gas reserves. The company says that this increases the verified reserves in the basin to 1,061bn m³. CNPC expects to expand the output from the area to over 10bn m³ by the end of 2019.

In order to ensure the success of this drive, the Chinese government extended unconventional gas production subsidies in June by three years. This is already having an effect, with state oil and gas companies increasing drilling activities.

But China’s complex geology and lack of technological breakthroughs may challenge these forecasts, with many outside China seeing them as optimistic. The question is what would China do to contain its energy import dependency if shale gas production expectations do not materialise. This is where coal, renewables and gas imports from friendly countries come in.

More coal and more renewables

Li Keqiang said in October that China’s coal industry needs to remain strong to play a key role in the country’s energy security, especially at a time of slow economic growth. He emphasised that energy security is China’s long-term strategic objective.

This has, in effect, reversed the country’s previous policy to reduce its dependence on coal. It will impact coal-to-gas switching, and it is likely to reduce LNG import growth further, especially since in the period 2015 to 2018 about 80% of China’s gas demand growth came from fuel switching.

China is also adding more clean energy to the country’s power generation mix.

During the last two years China has added 43 GW to its coal-fired generation capacity. In addition, a Global Energy Monitor (GEM) report released in November, states that the country “has more coal power capacity under development than any country.” Even though China is shutting down older and outdated coal-fired plants, “in total 195.6 GW is under active development, including 121.3 GW under construction and 22.6 GW permitted for construction.”

But the report also adds that China is a world leader in new coal technologies: 80% of the operational 1,000 GW thermal power plants have completed emission retrofits. In addition, in order to reduce coal use, the country is putting emphasis on increasing the proportion of thermal coal and reducing industrial raw coal consumption.

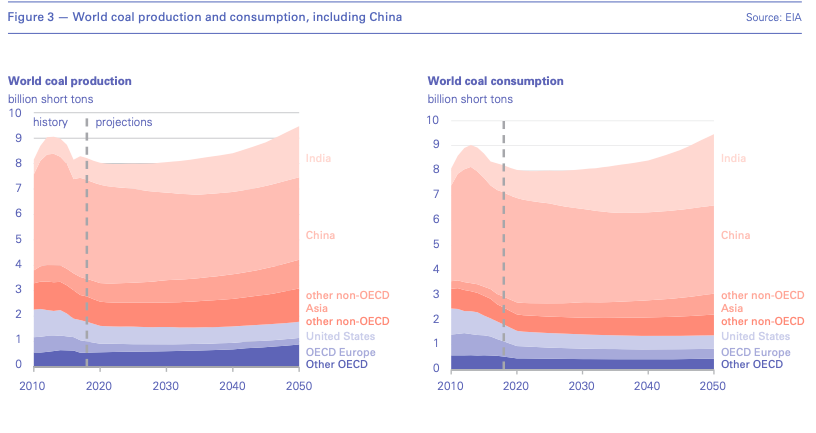

China’s longer-term coal dependency was highlighted in the recent US Energy Information Administration (EIA) ‘International Energy Outlook’ (Figure 3). China will be producing close to 32% of the world’s total coal production and will be consuming about 38% by 2050, it said.

Despite the call by the UN secretary-general at COP 25 in Madrid that “no new coal plants are to be built after 2020,” the indications from the country’s National Energy Commission in its new 14th ‘Five-Year-Plan’ (2021-2025) are that China may raise total coal-fired generation to 1.4 TW from 1.1 TW now. This is driven by grid stability requirements, energy demand projections, economic growth and energy security considerations. But cost is also a factor: gas is about five times more expensive than coal in China.

And yet, GEM states that “China’s continued expansion of its coal fleet is not inevitable.” The central government could push for “a transition toward clean energy.”

And indeed China is adding clean energy to the country’s power generation mix faster than any other country in the world. In addition, about half of the world’s electric vehicles operate in China. With energy demand growing, the country is also giving strong support to energy efficiency improvements, electrification, and continued expansion of renewable electricity supply.

The central government is committed to continue to promote clean energy, such as hydro, wind and solar power, but also nuclear and geothermal. The expansion of clean energy is a development goal for the FYP. This requires non-fossil energy to account for 20% of primary energy consumption by 2030.

Nevertheless, according to the IEA, China’s energy sector emissions hit a record high in 2018, accounting for more than half of the global increase in energy-related CO2 emissions and are still rising. Even though China has pledged to peak its energy-related carbon emissions by 2030 – as part of the Paris climate agreement – COP25 is increasing pressure on the country to act sooner.

Power of Siberia and possibly more

China developed a new energy security concept that calls for “mutually beneficial co-operation with other countries, diversified forms of development and common energy security through coordination” and is using this to address energy security concerns. Russia is seen as a potential long-term stable and reliable source of oil and gas for China.

The Power of Siberia gas pipeline is benefiting from this concept, combining the advantages of Russia's abundant resources and China's vast market.

CNPC is planning to build between 5 and 6 bn m3 of underground gas storage in depleted gas wells in Daqing, Liaohe and Jilin to cope with the off-season demand

China is already showing increasing interest for Power of Siberia 2, to the west. Previously known as the Altai gas pipeline, after trilateral discussions the 30bn m³/’yr line could now take a shorter route to China across Mongolia. Energy security concerns are making this increasingly likely, but it could also be an option should domestic shale gas production not rise to expectations. There is also another option: a smaller pipeline from Sakhalin Island.

Implications

The US-China trade war does not appear to be a short-term blip and it is causing irreversible, long-term, changes to China’s energy policies. As the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (OIES) pointed out: “The working assumption is now that US-China relations are likely to become increasingly fraught, well beyond the Trump era,” causing deepening mistrust and growing concern about energy security. As OIES says, China will “increasingly look to hedge against energy supply insecurity and limit its technological dependence on the US.”

Such measures are bound to affect the forecast in Figure 1 – particularly LNG imports – which does not reflect fully the impact of changing energy-security-related policies and China’s slower economic growth.

But China can source gas and LNG from what it considers to be “mutually beneficial co-operation” countries, such as Russia and east Africa. Chinese companies are already participating in Novatek’s Arctic LNG-1 and in Arctic LNG-2, as well as in Mozambique’s Rovuma LNG.

Even though China’s natural gas demand growth is slowing down, the country’s target to reduce air pollution is expected to continue to drive cleaner fuel and gas demand in the longer term.

Reflecting the challenges China is facing, Li Keqiang said in November that the country’s external environment may become more complicated with increasing uncertainties and challenges during the FYP, but, nevertheless, the country should set development as a primary task.

With energy security concerns listed in the NEA report as the number one challenge for the gas sector, emphasis is being placed on reducing gas import dependency, increasing domestic gas production, maintain reliance on coal, more renewables and clean energy and relying on friendly countries, such as Russia, for gas imports.