China's coal habit will be hard to kick

Rewind to the year 2000. The U.S. and China are the world’s two largest consumers of coal. Coal’s position in the U.S. has been spurred by the very large domestic coal resource endowment (about 25% of the world’s recoverable coal) and the tremendous expansion of coal-fired power generation capacity in late 1970s and early 1980s that was largely spurred by energy security concerns. Coal’s position in China has been supported by its own large domestic coal resource base (about 13% of the world’s total) alongside an astounding rate of economic growth that will prove to be transformative of the international landscape in multiple dimensions, including trade, energy, climate, and almost every aspect of geopolitics.

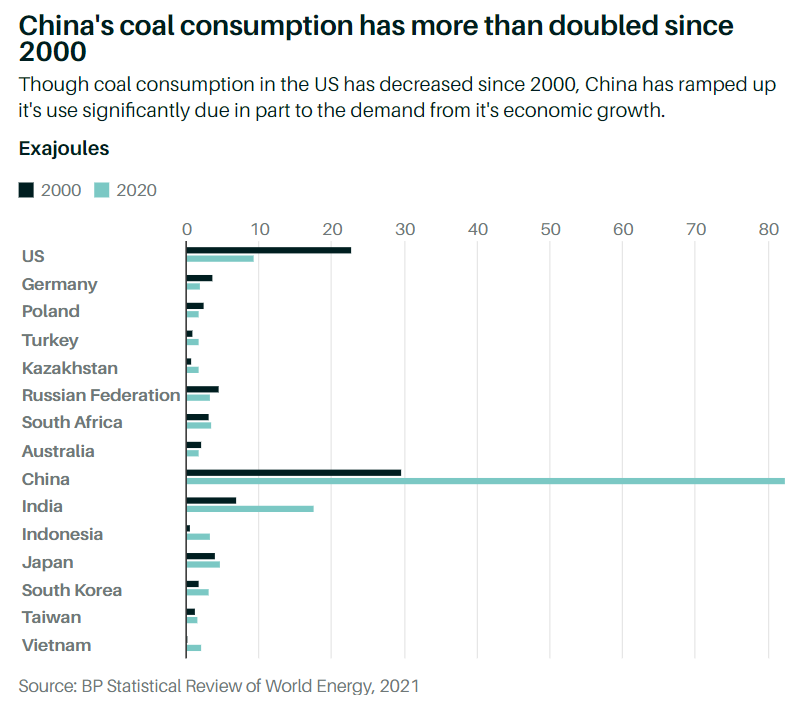

Advance to the present day. The world is still grappling with recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, and energy and economic systems are beginning to find their footing. U.S. coal resources are still enormous, but demand in 2020 was only 40% of what it was in 2000. China is moving in the opposite direction. Coal resources are still large, and economic growth has been driving astonishing trends in all forms of energy, including coal. China now accounts for over half of the entire world’s coal use, and it consumed 2.8 times more coal in 2020 than it did in 2000.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

This dramatic shift is evidence of two of the largest transitions in global energy over the last two decades: the shale revolution in the U.S. and economic growth in China. In the U.S., the shale revolution has made natural gas more economically attractive than coal, and low-cost gas has driven grid-level displacement of coal from power generation. In China, rapid economic growth has dramatically increased demand for all forms of energy, with coal being a large beneficiary.

Along with China’s emergence as a global economic powerhouse has come an overt effort by its leadership to be more influential globally. As part of this effort to extend international reach, China has been financing infrastructure projects across the globe, most notably through its Belt and Road initiative. But, apparently under pressure from the international community, President Xi Jinping announced before the U.N. General Assembly last month that China would cease building new coal-fired power generation capacity in countries outside of China. Given that China has been the largest provider of international finance for new coal capacity over the last decade, the announcement has significant implications for new coal investments in many countries around the world. As a result, the announcement has been widely touted as a game-changer for clean-energy investment, which would play to China’s geopolitical and strategic interests.

China’s massive influence on global supply chains for new energy resources is well-documented, and it is a strategic outcome resulting from investments that began decades ago. This has been made salient as OECD nations adopt policies that increase demands for minerals, metals, and materials that are critical for transitioning to greater electrification with more renewables and batteries. So, could Xi’s announcement be part of a strategic effort to secure global dependence on Chinese-dominated new energy supply chains? If so, it is short-sighted. Countries and manufacturers are already looking for ways to diversify supplies and decrease reliance on China.

For coal specifically, the question is still worth asking: Does Xi’s announcement matter?

To be clear, avoiding coal use anywhere supports climate goals everywhere, so not advancing coal capacity outside of China is beneficial. But Xi’s announcement, all else equal, does not mean that China’s domestic investments in coal use will decline. (It is also worth noting that Xi’s announcement has no bearing on coal investments in India, a large rapidly growing country with significant domestic coal resources.) China has a massive fleet of coal-fired power generation capacity—over 3,000 power stations with capacity in excess of 1,000 gigawatts. In addition, there are about 250 GW of additional capacity either under construction or in various stages of development. Absent a radical shift in domestic policy priority, coal use is set to grow in China over the next ten years, not decline, albeit likely at a slower rate than it has since 2000.

A radical shift in policy is not out of the question, but the direction of such a shift is anything but certain. In particular, given the recent power shortages experienced in China and the threat to industrial activity it has exposed, it is likely that China will refocus its efforts on its domestic power generation sector. Hitting or exceeding the state-planned target rate of economic growth is critical to leadership, and such growth is simply not achievable if electricity supply is not adequate or reliable.

Enter an old concept: energy security. Energy security is a principle that drives policies aimed at avoiding the economic dislocations associated with disruptions in energy supply or unexpected spikes in energy price. Electricity shortages are acute examples of disruptions in supply, and they trigger strong policy responses. China is no exception. Thus, the longer-term domestic policy response in China bears close attention. Will coal be leaned on more heavily than currently planned? Or, will other energy sources—natural gas, wind, solar, nuclear—be called upon more intensively?

Many will posit an answer, but there are headwinds in all directions. Coal is the most carbon-intensive option on the table, so its growth is not compatible with international climate goals. The current global natural gas market hardly argues for increased reliance on LNG imports. Wind and solar resources are zero-carbon, but they are also intermittent, which presents a challenge for reliability. Nuclear power is a zero-carbon option, but it is expensive and can take time to develop.

So, while we may not know with certainty how the future script will unfold, it is not a stretch to posit that energy security will be at the center of the plot. Any rational effort to address energy security will likely consider all energy sources in the portfolio of options that are available. For China, as with any nation, only its leaders can define that portfolio, which brings us right back to coal, an energy source that China has in large quantities. Of course, resource abundance alone does not guarantee coal will thrive (witness the U.S.) But, unlike the U.S., there is not an abundant, low-cost natural-gas resource readily available in China. The country’s coal fleet is very young, with a huge amount of capacity coming online in the last 10 years and more to come. Sheer megawatts alone indicate any effort to displace coal with other energy sources while also meeting existing and new demands will be more than Herculean. Hence, China will continue to use large amounts of coal for decades to come, even as other countries push forward with other energy sources.

Published by Baker Institute.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.