Carbon markets to get a shake up [NGW Magazine]

The UK announced in May that it would impose a new carbon pricing system to replace the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) once it leaves the EU. The EU itself is also planning changes, including a revision of the ETS to cover new fuel such as green hydrogen. At the same time, the scope of emissions covered by these schemes is set to expand from just power and heavy industry to include heating and transport, while carbon prices are expected to rise significantly over the next decade.

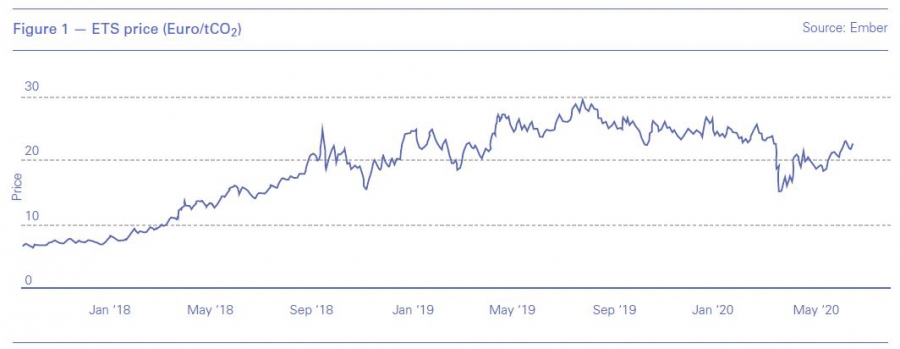

Brexit gives the UK the chance to apply a revised approach, avoiding the ETS’ perceived flaws, while co-operating with the EU ETS or its successor. The UK had already adapted the ETS to include a price floor of £18 ($22.3)/metric ton CO2, which kept UK carbon prices well above those elsewhere in Europe until summer 2018, in the process reducing coal-fired power generation (see graph). The UK government says the new system will be even more ambitious than previous versions, including an immediate reduction of the existing emissions cap by 5% by tightening the availability of credits. It will ensure the UK is aligned with its commitment to reach net zero by 2050.

Although few other details were revealed, the government said the new scheme also aims to provide a transition for businesses as the UK leaves the EU at the end of 2020, as well as offering greater flexibility “to work in the best interests of the UK”. Once the programme is up and running, the emissions cap may be revised downwards again, tightening supply and so pushing prices up. Energy minister Kwasi Kwarteng said: “The UK is a world-leader in tackling climate change, and thanks to the opportunities arising as we exit the Transition Period, we are now able to go even further, faster… This new scheme will provide a smooth transition for businesses while reducing our contribution to climate change, crucial as we work towards net zero emissions by 2050.”

EU ETS to be expanded, adapted

In the EU, as part of its ‘green deal’, the European Commission (EC) is expanding the ETS to include emissions from areas other than power generation and heavy industry, which are more difficult to measure and control. Carbon from flights within Europe is the first additional category to be included, bringing coverage up to just under half of all EU emissions. The next step, according to the EC president, Ursula von der Leyen, is to extend the scheme to road and rail transport, shipping and heating, which would increase coverage to over 90% of emissions. This is despite the fact that fuel is already taxed heavily in most EU countries. In 2018 an OECD study found that in 34 of 42 countries at least 90% of road transport emissions incurred taxes equivalent to a carbon price of more than €60/mtCO2, which is more than twice the ETS market price late in June.

These moves may have implications for trade, as they will add costs to many areas of business, putting them at a disadvantage to those outside the EU that have no carbon price. Stuart Broadley, CEO of the UK’s Energy Industries Council, said that, in the case of the UK, this competitive disadvantage meant that the UK government should be thinking about including embedded carbon import tariffs on all goods and services in the trade talks being conducted with countries that do not have carbon prices.

Not to do so would put local products at a disadvantage and customers would just keep buying imported high carbon products – which would undermine efforts to become a zero carbon economy in 2050.

“If we are to reach net zero by 2050, this [embedded carbon tariffs] is essential, and Brexit gives us an opportunity to include it in new trade deals,” he said. Only a fifth of global emissions are subject to a pricing scheme or soon to become so, with a current average price of $15/tCO2, according to The Economist.

There have also been calls from EU industry for similar protection – high carbon-intensity industries, such as steel, already receive compensation for paying carbon prices so that they compete with overseas producers on price. Further support, if it comes, is likely to be in the form of “border carbon adjustment” (BCA) mechanisms, which in effect are tariffs on products from countries that are not members of a carbon-pricing scheme.

The EU says it will propose a BCA mechanism next year as part of the expansion of the ETS. In the US, the Democratic Party has also proposed border adjustments to stop climate plans hurting the competitiveness of US companies.

Making room for hydrogen

In addition, as part of the EU’s new hydrogen strategy, the ETS requires further reform in order to recognise the carbon abatement achieved by replacing natural gas with green or blue hydrogen. Meeting in mid-June, ministers from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and non-EU member Switzerland, committed to look at the role of CO2 prices in developing a hydrogen market, as well as taxes, levies and tariffs in sector coupling between electricity and gas.

The UK government is also keen to encourage hydrogen production and the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS), which may affect the design of its new system.

Getting the pricing right

To date, most emissions trading systems work by capping the total amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted by certain sectors, and after each year, companies must surrender enough carbon allowances to cover their emissions or pay the difference. Carbon allowances can be traded and the overall cap (amount of credits) is reduced over time in order to drive decarbonisation. As more areas come under the remit of carbon schemes, assessing the amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted becomes more complex. In the EU ETS’ case, this approach has also led to low prices – at least until a tightening of the cap in 2018 – which provide too little incentive to decarbonise.

The answer to both problems appears to be in reform of the EU’s Market Stability Reserve (MSR), which controls the amount of ETS credits issued. This would take the form of a switch to focus on prices, rather than quantities of carbon allowances, making it a Price Stability Reserve, rather than an MSR – and there are calls for this to be done at an upcoming review in 2021. The switch would make it easier for policy-makers to control prices, and avoid the complexity of assessing volume allowances as the range of emissions included widens.

The UK may also opt for this approach, given its focus on ensuring a price floor in the past. In May, the French-German initiative for the European recovery from the coronavirus crisis also recommended the introduction of minimum carbon pricing in the EU ETS.

Carbon pricing gains traction

Carbon pricing appears to be gaining popularity as a policy tool. According to the 2020 Refinitiv Carbon Survey, the EU ETS has overtaken national climate policies and is now widely seen as the most important driver in tackling carbon emissions. In the survey, 43% of respondents said the ETS will have a major impact – a much higher share than the 27% that said national climate policies and other EU-wide climate policies would be major factors. This marks a reversal in opinion from the 2019 edition of the survey, when the EU ETS scored 35% and national climate and energy policies scored 43%.

Outside Europe there are also carbon prices in Canada and parts of the US, including California. Canadian prices are set to rise quickly – from a minimum of C$20 ($14)/metric ton CO2 since January this year, up to C$50/mt in 2022. South Korea is also introducing a system, and China had planned to introduce one for its power sector by the end of the year. In addition, in 2021, 70% of global aviation emissions were scheduled to enter a UN emissions-trading programme which aims to cap them at 2020 levels, although this may be less urgent now given the collapse in aviation miles since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Leading economists say carbon prices need to be in the range of $40-80/mt to be effective (as well as some other interventions), which is in line with what most observers expect in Europe in five or ten years. And it must cover all types of greenhouse gas emissions, including leakage, which is the direction most policies are taking, although there is some distance to go.

Oil and gas companies are increasingly aware that this will affect their operations, prompting European majors to introduce their own zero, or close to zero, carbon targets. Efforts are already underway. For example, last month Total signed a deal with Siemens to develop solutions to decarbonise the production of LNG, while BP, which has made big plans to decarbonise, is counting on a carbon price of $100/mt (or its equivalent) by 2030. That would lift many costly projects such as carbon capture and sequestration into profitability, although only at great expense to consumers.